Dan Guild reviews presidential polling since 1976 to gauge the impact of televised debates. -promoted by Laura Belin

Since the advent of television, politics and indeed history have occasionally turned on a few moments. Seldom do they last longer than 60 seconds (like wit, television values brevity above all else).

Senator Joe McCarthy, and the moment he led, were stopped when he was asked, “Have you no decency, sir?” During the Watergate hearings, Howard Baker summed up the entire scandal when he asked, “What did the president know, and when did he know it?”

Some of the game-changing events have happened in debates. Ronald Reagan revived his flagging campaign in 1980 during a debate about a debate. Later that year, he uttered two phrases that seemed to sum up the entire election. “There you go again,” he said in response to President Jimmy Carter’s attack on his position on Social Security. (During Reagan’s presidency, Carter would be proven right.)

But even more memorable is Reagan’s close, from the final debate in late October 1980:

The country would answer the question with a resounding no.

There can be little doubt that the Joe Biden and Donald Trump campaigns have spent months looking for that one phrase, that one moment that defines the campaign. Reagan’s question has been used against every incumbent since 1980 in different ways. Bill Clinton asked it, if not in so many words. I have little doubt Biden will too.

In previous posts, I have drawn parallels between this year’s election and 1980. Like Carter, Trump has been consistently unpopular (to be clear, Carter is ten times the human being Trump is). As in 1980, the populace senses the country is badly off track now. Perhaps more fundamentally in 2020 than in 1980, Americans feel divided and sense that the current president cannot heal the divisions.

This chart summarizes the impact of presidential debates since 1976.

A couple of things to note on the day of the first Trump/Biden debate:

The same was true in 2012: Obama led by 3.8 percent going into the first debate. He even trailed after the first debate. But in the end, his final advantage in popular vote share was nearly identical to his pre-debate average.

These are the polling averages before and after each debate. In some years it is not possible to differentiate between polling after one debate and before the next one.

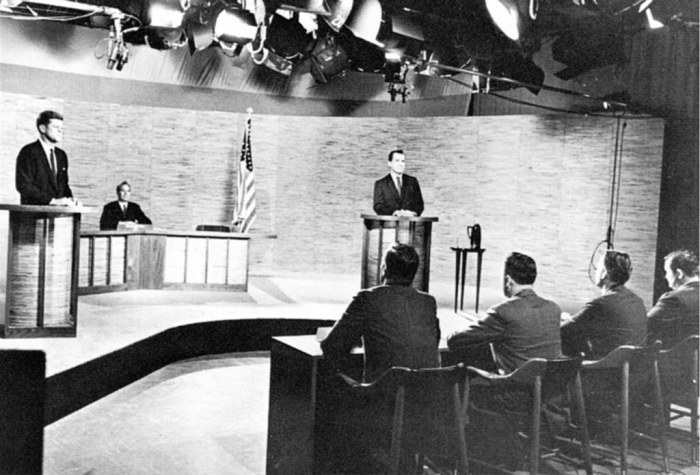

Top image: United Press International photo of the second debate between John F. Kennedy (left) and Richard Nixon, which took place on October 7, 1960.