Herb Strentz: Some lines from the Declaration of Independence “remain sacred even in these days of skepticism, cynicism, and mutual betrayal. In a way, they got us here and they offer a way out.” -promoted by Laura Belin

Happy Fourth of July!

That opening is neither a belated salutation for 2020 nor a head start on Independence Day 2021.

Rather it suggests it may be a good idea to keep the Fourth in mind to stay sane through the 100 and more days we face of political rhetoric, folly, hatred and the like until the Nov. 3 election — unless, of course, that is called off or rigged as some of the fears go.

Remembering the Fourth is like hearing at a place of worship that one should celebrate and practice one’s articles of faith every day — not only on days of festival and commemoration.

So let us focus on how we “hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness;” and that, to those ends, “we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.”

Those lines remain sacred even in these days of skepticism, cynicism, and mutual betrayal. In a way, they got us here and they offer a way out.

Here are two other thoughts–not from the Declaration of Independence–to help get us all the way to Nov. 4.

Philosopher Jacob Needleman wrote in The American Soul,

[…]the founders of our country did not fight and die for the right to be selfish and self-involved, nor did they make holy cause of the childish impulse to have no constraints upon ourselves, to get just what we like or want whenever of however we want it. They did not risk so much just so that a man or woman could live and act independently of obligation to society.

And historian Gary Wills, in Inventing America, suggested we have three Declarations: a political one adopted by the Second Continental Congress in 1776, a philosophical/scientific one by Jefferson and the symbolic one of our civil religion, parades and fireworks.

Wills cautions,

The Fourth includes celebration of some things that happened on different days and of other things that did not happen at all [….] The Declaration has been turned into something of a blank check for idealists of all sorts to fill in as they like. We had better stop signing it and begin reading it.”

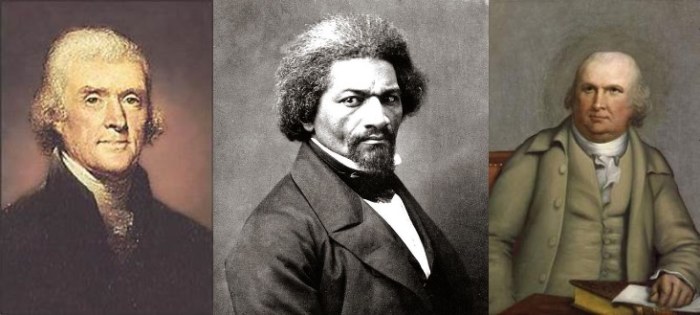

Consider four others who provide perspective for the days ahead: Robert Morris, whose story speaks to the pledge of “our lives, fortune and sacred honor;” the fictional Big Brother, the tyrant of Oceania in George Orwell’s 1984, and happily the non-fictional Thomas Jefferson and Frederick Douglass, who seems to have had it right back in the 19th century and today in the 21st.

Lines in a draft of the Declaration condemned slavery, but put the blame on England’s King George III: “He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery […]” Historian Wills called this wording “morally convoluted,” and said deleting it spared the Declaration from ridicule, given how many in Congress were slaveholders.

Further, the Declaration was written not only for those in the colonies, but also as an argument for support from other nations — chief among them France — where readers would be well aware of the hypocrisy in blaming George III for slavery in the colonies and less inclined to support a war for independence. In a way that’s the curse of holding noble ideas; you’ll also be a hypocrite because you cannot live up to the ideals you cherish.

Another quote from Jefferson speaks to this. His views are reflected in his remorseful 1785 renunciation of slavery, a portion of which is inscribed on the Jefferson Memorial: “Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever.”

Fast-forward some 70 years, and you are in Rochester, New York, at a Declaration celebration on July 5, 1852. The orator is the former slave, Frederick Douglass. He asked,

Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak today? […]

To the American slave […] your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license […] your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery. […]

Nevertheless, he also said,

Your fathers staked their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor on the cause of their country […] With them justice and liberty were final; not slavery and oppression […] They seized upon eternal principles, and set a glorious example in their defence […].

Writing about the Douglass oration, Needleman notes that one cannot truly love this nation unless also acknowledging its shortcomings and its nightmares and failures, and that people who find only fault with the nation are dishonest if they do not acknowledge its strengths and triumphs.

As Douglass said toward the end of that oration, “I do not despair of this country […] I therefore leave off where I began, with hope.”

Herb Strentz was dean of the Drake School of Journalism from 1975 to 1988 and professor there until retirement in 2004. He was executive secretary of the Iowa Freedom of Information Council from its founding in 1976 to 2000.

Top image: From left, Thomas Jefferson, Frederick Douglass, and Robert Morris.

1 Comment

A fan, Diane Kolmer

An excellent historical perspective that reminds us that none of us are holier than thou.. and our mission.. as Frederick Douglass admonishes, is to keep seeing the failures and enacting laws and social and cultural change to become that “…more perfect Union.”

gmcgdem Fri 10 Jul 2:36 PM