Forty-three years ago this week, Congress overrode a presidential veto to enact an appropriations bill containing the first ban on federal funding for abortion. Republican U.S. Representative Henry Hyde of Illinois had proposed language prohibiting Medicaid coverage of abortion during House debate on what was then called the Health, Education, and Welfare budget. Ever since, the policy has been known as the “Hyde amendment.”

Four Iowans who served in Congress at the time spoke to Bleeding Heartland this summer about their decisions to oppose the Hyde amendment and the political context surrounding a vote that had long-lasting consequences.

THE IOWANS IN CONGRESS IN 1976

The 94th Congress represented a high-water mark for Democrats in Iowa and nationally, as the party expanded its majorities in the post-Watergate 1974 landslide. Democrat John Culver defeated David Stanley in Iowa’s open U.S. Senate race, joining fellow Democratic Senator Dick Clark. Tom Harkin and Berkley Bedell defeated Republican incumbents in U.S. House races, a feat not repeated in Iowa until Abby Finkenauer and Cindy Axne prevailed against Rod Blum and David Young last November.

For only the second time in Iowa history, Democrats represented all but one of the state’s U.S. House districts. (The same was true for one term after the 1964 election.)

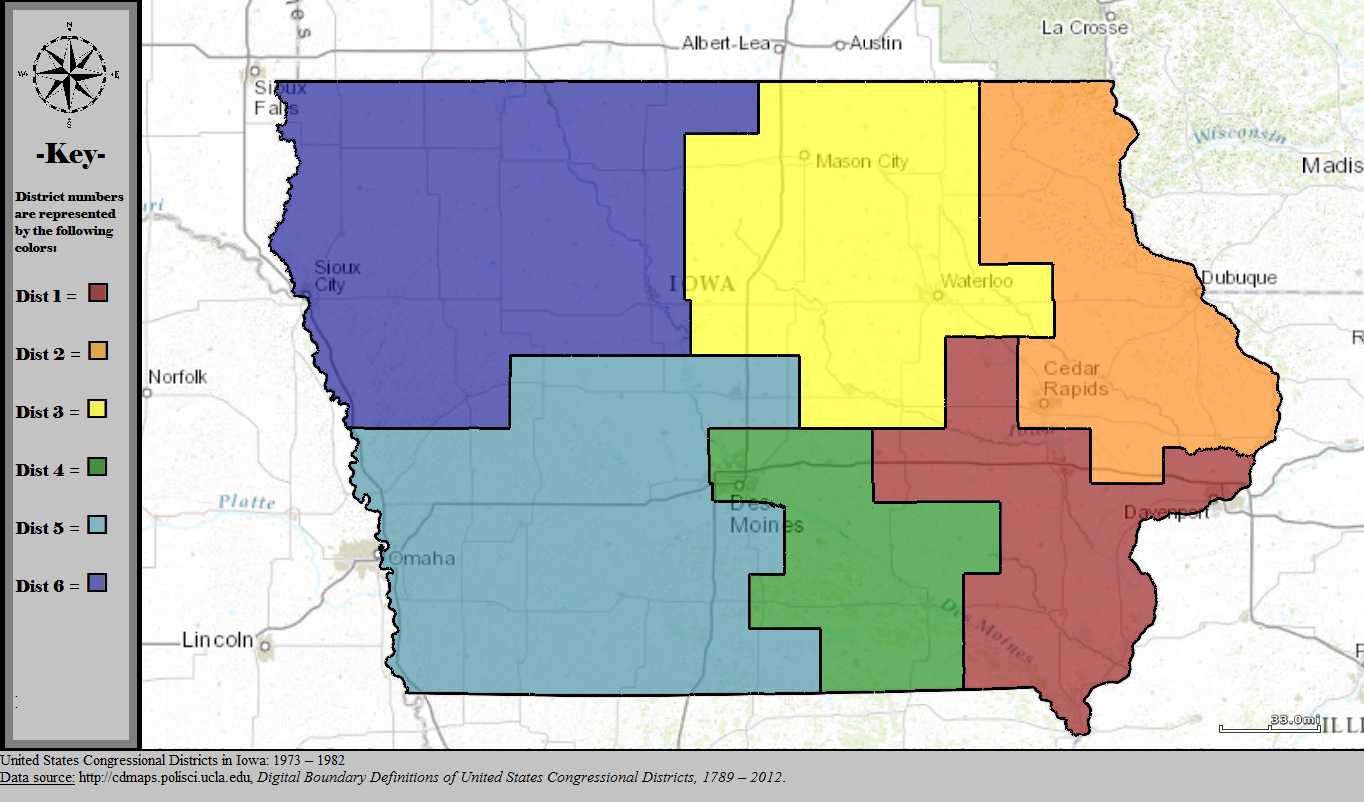

Here’s the Iowa Congressional map from the 1970s.

Representing each district in 1975 and 1976:

IA-01 (red): Democrat Ed Mezvinsky

IA-02 (orange): Democrat Mike Blouin

IA-03 (yellow): Republican Chuck Grassley

IA-04 (green): Democrat Neal Smith

IA-05 (light blue): Democrat Tom Harkin

IA-06 (dark blue): Democrat Berkley Bedell

Mezvinsky, Smith, Harkin, and Bedell shared memories about the Hyde amendment debate and its aftermath in telephone interviews during June or July.

Blouin did not reply to multiple phone messages and e-mails seeking an interview. Staff for now-U.S. Senator Grassley did not respond to Bleeding Heartland’s interview requests or questions submitted by e-mail.

THE CONGRESSIONAL DEBATE ON THE HYDE AMENDMENT

Although the Hyde amendment went into effect on September 30, 1976, the crucial House votes happened three months earlier. The indispensable Govtrack website shows all of the June 24 votes on the health, education, and welfare appropriations bill.

Hyde offered an amendment “prohibiting funds under Title II to be used to pay for abortions or to promote or encourage abortions.” The Illinois Republican would have preferred a broader prohibition, he said during debate: “I would certainly like to prevent, if I could legally, anybody having an abortion, a rich woman, a middle class woman, or a poor woman. Unfortunately, the only vehicle available is the HEW Medicaid bill.”

House members approved Hyde’s amendment by 207 votes to 167. Grassley and Blouin (who represented the heavily Catholic Dubuque area) voted yes, while Iowa’s other four House members voted no.

The proposal came up for another vote later the same day. The Congressional Record shows that Representative Bella Abzug, a Democrat from New York, said in a speech,

A good number of Members who voted on this amendment indicated to us that they had not really understood the depth or the breadth of this amendment. This amendment, in effect, provides that no funds will be permitted in the medicaid program for any abortion whatsoever. […]

The important thing that was not realized by Members voting on this amendment was that this amendment is a very broad one, one that would prevent a therapeutic abortion and prevent action being taken to save the life of a mother. […]

I know again that there is much too much humanity and compassion in this House not to expect that some would want to reconsider their votes.

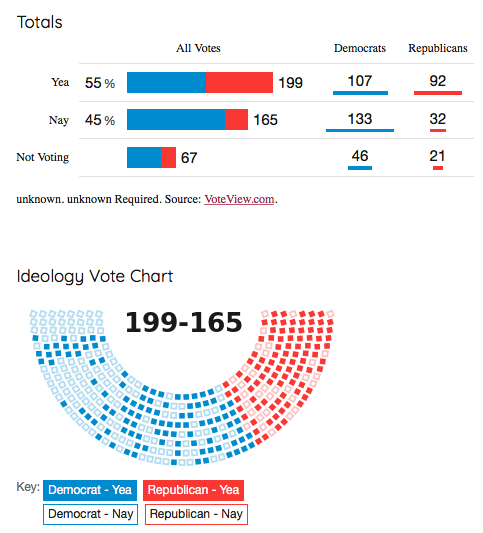

Before a vote on final passage of the appropriations bill, House Speaker Carl Albert gave members an opportunity to demand a separate vote on any amendment that had previously been debated. Abzug called for a vote on Hyde’s amendment, which passed by 199 votes to 165, with 67 not voting. Again, Blouin and Grassley supported the policy, while Mezvinsky, Smith, Harkin, and Bedell voted no.

Normally, legislation needs 218 votes (a majority of the 435 House members) to be approved. Hyde’s proposal passed with fewer votes, because of the large number not voting. Many of those lawmakers were in Washington that day but preferred not to take a public stand on this issue.

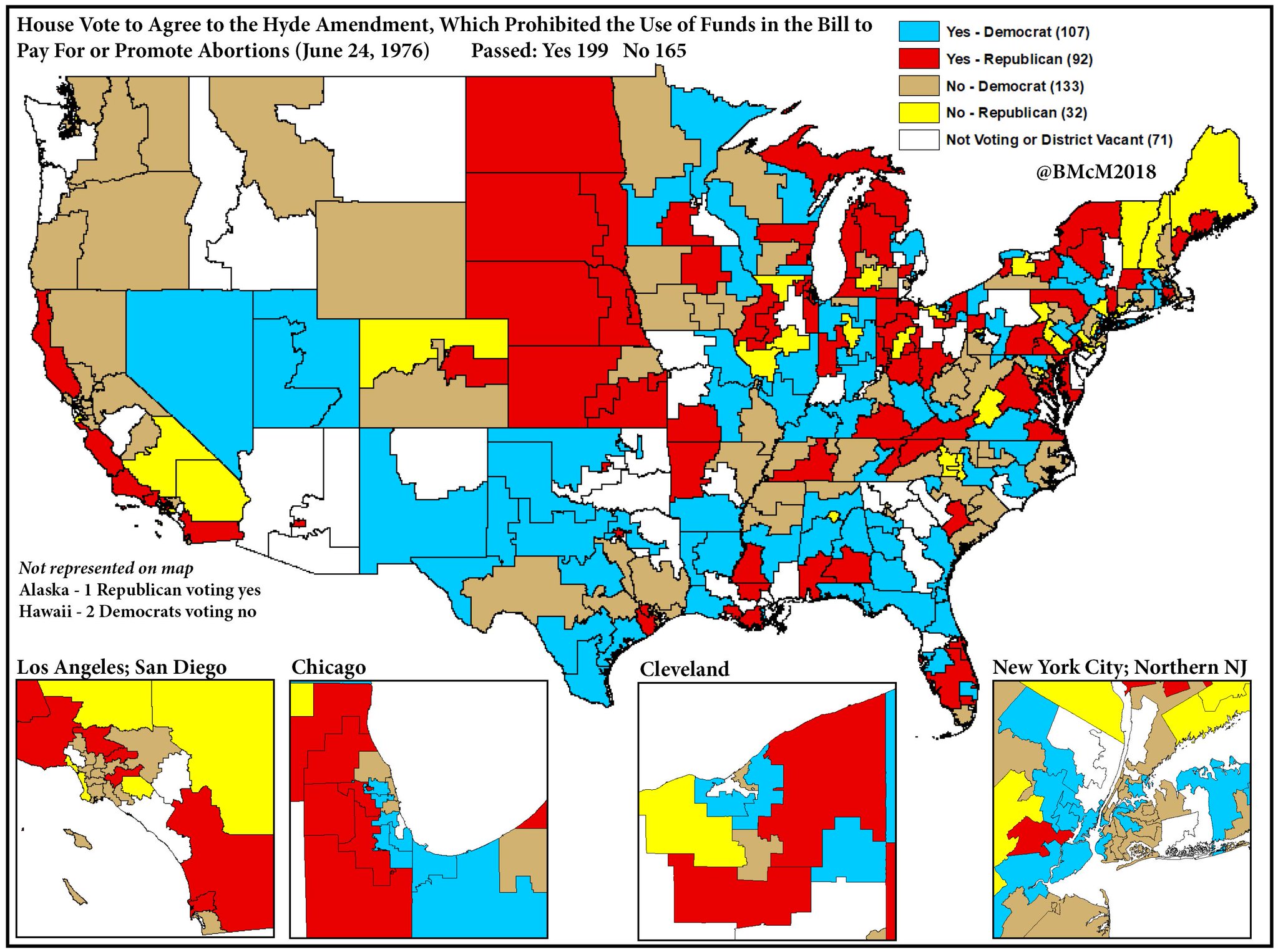

The dispute over Medicaid abortion funding split both party caucuses. The roll call shows 107 Democrats (about 45 percent of those voting) and 92 Republicans (74 percent) for the Hyde amendment, while 133 Democrats (55 percent of those voting) and 32 Republicans (26 percent) opposed the policy.

Twitter user Barry (@BMcM2018) gave me permission to republish the map he created in June to commemorate this vote.

Govtrack visually represented the Hyde amendment vote this way.

The Senate removed the Hyde language from the appropriations bill in a June 28 vote that divided both caucuses. Iowa Senators Clark and Culver both supported deleting the section that banned the use of federal funds for abortion.

The bill then went to a conference committee, where negotiators agreed on a compromise in August. The House approved the conference report, but in a separate vote, refused to agree to the Senate amendment striking the Hyde language. The Iowans split the same way they had in June, with Grassley and Blouin insisting on the abortion funding ban.

Senators weren’t ready to concede this fight. In late August, the Senate refused to concur with the House amendment and insisted on deleting the Hyde language. Back to conference committee the bill went.

All six Iowans voted for the second conference report on the House floor in mid-September. Harkin recalled during our interview, “Sometimes you just have to vote for an appropriations bill, even though it’s got stuff in it you don’t like.” Culver and Clark voted against the bill with the Hyde language on the Senate floor, but it passed anyway.

President Gerald Ford vetoed the spending bill for reasons unrelated to the Hyde amendment. Every Iowan was a “yea” on the House and Senate votes to override that veto on September 30.

Since 1976, Congress has repeatedly reauthorized the Hyde language. It’s not a stand-alone law, but has been “attached as a temporary ‘rider'” to the appropriations bill for the Department of Health and Human Services, which administers the Medicaid program. As Alina Salganicoff, Laurie Sobel, and Amrutha Ramaswamy wrote in this Kaiser Family Foundation explainer, “For many low-income women, the lack of Medicaid coverage for abortion is effectively an abortion ban.”

Did you ever consider voting for the Hyde amendment? Was it a hard choice?

“Everybody considered voting both ways. Everybody did,” Smith told me. “Whichever way you voted, it was a difficult vote.”

Mezvinsky recalled, “No. Never thought of it. I mean, I analyzed it, looked at it. But it wasn’t on my radar screen.”

Bedell concurred. “It was not difficult. I didn’t have to worry particularly about pleasing my constituents on how I voted. I won by enough that I could vote whatever I believed in.” Was he ever concerned about opposing something the residents of his district wanted? “When I voted against [President Ronald] Reagan’s tax cut [in 1981], that was about the worst vote I could have possibly made for northwest Iowa. [laughs] But they still re-elected me just the same.”

Harkin and Blouin were the only Catholics in Iowa’s Congressional delegation. Harkin had attended Catholic high school and law school too. Asked whether the Hyde amendment was a hard vote for him, Harkin said, “Not really.” He talked it over with his staff and his wife Ruth Harkin ahead of time. “I don’t remember it as a very difficult decision, no. It was just something I wasn’t going to support.”

Why didn’t you support the Hyde amendment?

Mezvinsky tied his decision to his Jewish faith and his upbringing. Growing up in Ames, his father taught him that “when someone was hurting financially, you helped them out. And in comes the Hyde amendment, that basically discriminated” against the poor, as well as against African Americans.

Several women in the House Democratic caucus influenced Mezvinsky’s views as well. Barbara Jordan was a good friend; the two sat next to each other on the House Judiciary Committee. He was close to Elizabeth Holtzman and Pat Schroeder too. He regularly discussed controversial issues with them, which “really made a big difference.” He also greatly respected Bella Abzug and Shirley Chisholm, among the most vocal Congressional opponents of the Hyde amendment.

Mezvinsky remembered that many House Democrats felt Congress should work on reducing unplanned pregnancies, “instead of focusing on discrimination.”

Harkin and Bedell were first-termers representing traditionally Republican areas. Nevertheless, Harkin told me the two decided “we couldn’t support this because it was obviously discriminatory against poor women. That’s all it was.” With the Hyde amendment in place, “if you’ve got money, and you’re well situated, yeah, you can terminate a pregnancy. But if you’re poor and you rely on Medicaid, tough luck.”

Bedell had “about a million reasons” for voting against the Hyde amendment, he said. High on his list: women should be able to control their own bodies. In addition, overpopulation was perceived as a global problem during the 1970s.

How did a Republican amendment to an appropriations bill get a vote on the House floor?

Nowadays the minority party is restricted from offering amendments on much of the legislation that reaches the House floor. But the chamber operated differently then.

“It wasn’t unusual at all. We had open rules,” Harkin said. “Anybody could offer an amendment.” He was able to get the first human rights amendment added to a foreign aid bill in 1975. “This whole thing about closed rules is a recent phenomenon initiated by Republicans. And now Democrats are starting to play that game too. It’s terrible.”

Bedell confirmed it “wasn’t unusual back then” for members of the minority caucus to offer amendments on the floor.

Was there pressure ahead of time to vote for or against the Hyde amendment?

No one recalled Democratic leadership in the House pushing members to vote either way. “Right away it was recognized as something that was, no matter which way you vote, somebody’s going to have a legitimate criticism,” Smith said.

Harkin didn’t remember any large Democratic caucus meeting to discuss this issue. Having reviewed the roll call on the vote before our interview, he was struck by the fact that 32 Republicans voted against the Hyde language. Although many Democrats representing conservative areas were yes votes, there were a lot of Democratic opponents even in the southern states. (Those districts are brown on Barry’s map, posted above.)

Harkin noted that his good friend Bob Drinan, a Jesuit priest from Massachusetts, also voted against the Hyde language, because of its impact on the poor. “In my memory, this was not so much an abortion/anti-abortion vote as it was a fairness kind of vote. Should poor women be discriminated against?”

While some Catholics may have seen the Hyde amendment as an abortion vote, Harkin acknowledged, “I don’t remember it as an anti-abortion vote, I remember it more as a discriminatory vote in 1976. Now later on [as the policy came up for reauthorization], it became an abortion vote.”

As for members of the public, Bedell didn’t recall getting a lot of communications before the vote. Smith heard from some constituents on both sides of the issue. Mezvinsky noted that while IA-01 contained some largely Catholic communities, “I didn’t have the pressure point that [Blouin] had, coming from Dubuque.”

Did members of the Iowa delegation talk about the vote beforehand?

“Yes, yes they did,” Smith told me. “Everybody talked about it,” and everyone understood it was a particularly difficult vote for Catholic members.

Smith added that Hyde wasn’t sure he had enough support to pass his amendment. Entering the House chamber that day, he saw the Republican “standing there as people came in the door asking for votes.” Someone must have already told him Smith planned to oppose the amendment, because “He said, ‘Go on, I know I’ve lost your vote.'” (According to Hyde’s New York Times obituary, “he was surprised to win that vote.”)

Harkin said there was no lasting animosity in the House Democratic caucus after the Hyde amendment passed. People didn’t talk much about it.

A lot of House members dodged this vote. Did you ever consider not voting on the Hyde amendment?

“That was the easy way out,” and in some respects “the best way out,” Smith said. “I don’t think anybody can fully understand the pressure that was on members of Congress at that time.” But he wasn’t going to avoid the vote. “You just have to hope that people understand the explanation, but a lot of people don’t understand.”

The others also said they didn’t seriously consider not voting. Mezvinsky had dealt with other contentious matters, going through hearings on impeaching President Richard Nixon. He remembered that after voting for all five articles of impeachment in the House Judiciary Committee, “it was a volatile time.” Some people yelled at him or even threw stones when he was back in the district. Still, “You don’t avoid those issues. […] It wasn’t a question, not at all.”

Was there a lot of backlash after you voted against the Hyde amendment?

Bedell doesn’t remember getting a lot of letters from constituents. “It was not a controversial issue in my district.”

Mezvinsky commented that the reactions were “not as extreme then,” though “the right to life movement was vocal.” While some people expressed strong views, “You didn’t have quite the evangelical response that you have now. It wasn’t as organized, per se.”

He generally didn’t focus on public opinion. In politics there is a philosophical debate over how much representatives should reflect the views of constituents, Mezvinsky explained. While some “simply try to mirror others,” he “took a Burkean” approach.

My view was that it’s also part of your responsibility as a member of Congress to lead your constituency, to try to educate them. They may not accept the education, they may not like what they hear, but that’s the philosophy that I felt was important as a representative.

Mezvinsky thought the way to talk about abortion was to emphasize how public policy should tackle unplanned pregnancies for “all races and wealth levels.”

Looking through the Des Moines Register archives from late June 1976, I couldn’t find an article or editorial about how the Iowans in Congress had voted on Medicaid funding for abortion. That surprised me, since the Register had an active Washington bureau in those days and frequently reported on Congressional happenings. Bedell didn’t recall a lot of media attention afterwards either.

Smith posited, “There was no way to realize at the time that it would become such a controversial amendment.” People didn’t know “whether it was going to survive the next step.” It hadn’t passed the Senate and eventually was tied up in court for years. (A federal judge initially put an injunction on the Hyde amendment and ruled it unconstitutional, but the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the ban on federal Medicaid funding for abortion in 1980.)

Did your vote on the Hyde amendment affect your 1976 re-election campaign?

Smith represented relatively safe Democratic territory. He was re-elected that year with more than two-thirds of the vote. (Click here for county-level numbers for all Iowa Congressional races.)

Though his district was more conservative, Bedell typically won easily and took 67 percent of the vote that year. “It was a completely different world back then,” he told me. “And the partisanship was not nearly what it is, well, it’s nothing like today.” Bedell continued to win by large margins until he retired in 1986. No Democrat has represented northwest Iowa in Congress since.

Harkin didn’t recall abortion coming up at all during his 1974 campaign, even though it was the first election after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Roe v Wade decision. Because IA-05 was a “tough district,” Harkin anticipated a difficult race in 1976 against Kenneth Fulk, who was the head of the Iowa State Fair. But as far as he remembers, Fulk didn’t bring up the Hyde amendment. “I don’t know, I think it was just too soon,” and the anti-abortion forces hadn’t coalesced at that point. Harkin carried nearly 65 percent of the vote.

Abortion became a more salient issue in the 1978 race to represent IA-05, when the GOP challenger was Julian Garrett (who now serves in the Iowa Senate). Harkin remembered a picture being taken that year with people trailing behind him in mostly-Catholic Carroll carrying anti-abortion signs, protesting his vote on the Hyde amendment. It was a big issue again during his 1980 re-election campaign, even though Harkin continued to win Carroll County.

The only Iowan in Congress to lose his 1976 re-election bid was Mezvinsky. Jim Leach defeated him by 51.9 percent to 47.8 percent. Mezvinsky didn’t think the Hyde amendment played a role. The main argument against him was his voting record was “too progressive” and didn’t reflect Iowa.

Mezvinsky allowed that the Hyde amendment “may have been an undercurrent.” The Quad Cities and some other southeast Iowa towns had a large Catholic population. Then again, Mezvinsky lived in Iowa City and also represented Grinnell, where most people were in line with his views on abortion. “In the grand scheme of things,” other factors were more important.

Leach agreed, telling Bleeding Heartland via e-mail, “I doubt if the issue had electoral consequences in the 1976 election.” He didn’t campaign on the topic and speculated that in the Democratic-leaning district, activists opposing the Hyde amendment probably outnumbered supporters of the policy. During 30 subsequent years in Congress, Leach was a progressive Republican, pro-choice but with a mixed voting record on abortion-related legislation.

Blouin, the only Iowa Democrat to vote for the Hyde amendment, was barely re-elected in 1976 with 50.3 percent of the vote to 49.1 percent for Republican Tom Riley. Two years later, he lost his bid for a third term to Tom Tauke.

Top image: Official photos of U.S. House members from Iowa during the 1970s. From left: Ed Mezvinsky (IA-01), Neal Smith (IA-04), Tom Harkin (IA-05), and Berkley Bedell (IA-06).