Rick Morain is the former publisher and owner of the Jefferson Herald, for which he writes a regular column.

On October 14, the state of Iowa observes Indigenous Peoples’ Day, in recognition of the roles native tribes have played in the state’s history and culture. It’s not a federal holiday, but an increasing number of states and cities now observe it instead of Columbus Day, the traditional name for the mid-October holiday. (Governor Kim Reynolds made the change in Iowa in 2018.)

October 11 was the anniversary of another notable event in Iowa history: on that day in 1842, the Sauk and Fox tribes signed a treaty ceding to the United States a large chunk of central and southern Iowa, including what is now Greene County. (The term “Sac and Fox” is a designation historically employed by the American government. A more accurate term is “Sauk/Meskwaki.”)

John Chambers, Governor of Iowa Territory, signed the treaty on behalf of the United States. Representing the Sauk and Fox tribes were 44 signatories and witnesses, led by Keokuk for the Sauks and Poweshiek for the Foxes. The event took place at the government’s Sac and Fox agency in today’s Wapello County, a few miles east of present-day Ottumwa and just north of the Des Moines River.

Under the terms of the treaty, several thousand Sauks and Foxes agreed to cede all their remaining lands west of the Mississippi River. (They had already ceded their land in Iowa east of the chunk represented by the 1842 treaty.) They could remain on the western half of their 1842 treaty lands—the portion including what is now Greene County—for three years, but then would have to move to a tract on the Missouri River or on its tributaries.

In return, the U.S. government agreed to pay the Sauks and Foxes annually the sum of 5 percent of $800,000, amounting to $40,000. In today’s dollars that amount is the equivalent of about $1.5 million. In addition, the government would pay enumerated tribal debts of $258,566.34, about half of which were owed to Pierre Chouteau Jr. & Co., the St. Louis merchant company that had specialized in fur trading.

The government would also set up two blacksmiths’ and two gunsmiths’ shops near the tribes’ agency on their new lands, mostly paid for by the tribes. The cost of the tribes’ removal, and funds for their subsistence for the first year at the new location, would be paid by the government.

In addition, $500 would be paid annually to “the principal chiefs of the Sacs and Foxes” to be used however they wished, with the approval of their government agent.

Of the $40,000 annual payment, $30,000 would be placed in the hands of the government agent to be expended by the chiefs, with the agent’s approval, for tribal and charitable purposes among their peoples. Funds designated for agricultural and milling purposes from an earlier treaty would be combined with the 1842 treaty funds.

Three years after Iowa became a state in 1846, Truman Davis brought his family up the Raccoon River from Adel to become the first non-indigenous settlers in Greene County.

The Sauks and Foxes were not tightly governed. Several factions had developed, with major divisions between those who felt it expedient to agree to the American demands, and those who wished to oppose them. Keokuk and Poweshiek were principal leaders of the “pacific” group. The opponents harked back to Black Hawk, who had tried in 1832 to maintain their tribal lands east of the Mississippi River in Illinois around the tribal community of Saukenuk.

So not all tribal members agreed to the conditions of the Treaty of 1842. As a result, when the time prescribed for removal to the Missouri River area arrived, a number of Sauk/Meskwaki stayed in Iowa in violation of the terms of the treaty. It took several years before removal was completed.

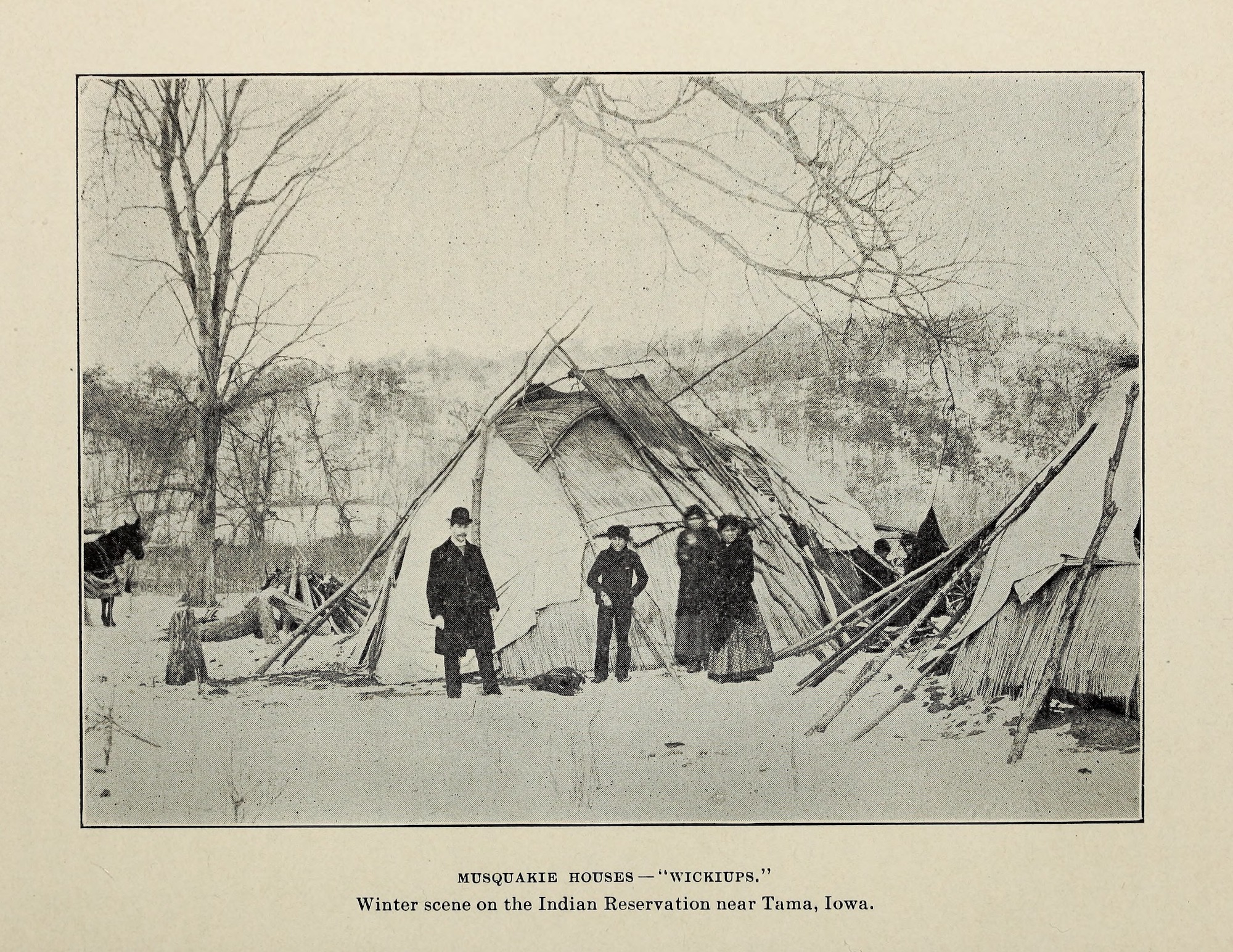

And in 1856, a number of Meskwakis used their government allotment money and other funds to purchase land near Tama and return to the state, where their settlement continues today.

The Treaty of 1842 was one of nine treaties between the federal government and indigenous tribes that gained the United States the ownership of Iowa’s land and moved the tribes westward. Some initially went to Kansas and later ended up in Oklahoma, called “Indian Territory” until it became a state.

The cessions in Iowa ended up costing the U.S. government about eight cents per acre. In contrast, under the federal Preemption Act of 1841, American squatters on federal land could buy 160 acres for $1.25 an acre if they stayed on the land for a specified length of time and improved it.

When the Meskwaki purchased their settlement site near Tama in 1856, it cost them $12.50 an acre to buy the land their tribe had ceded to the U.S. government for eight cents an acre in 1842.

The long history of the exploitation of America’s original inhabitants, like that of African slaves, is sometimes excused as inevitable in its times. Both patterns of exploitation boosted the country’s economic progress at the expense of many inhabitants.

Could we have done better for the country’s non-citizens? No doubt the answer is yes.

2 Comments

Great piece from Rick

It is important to teach the history, how settlers took the land away from the natives. They used dirty tricks, deception, violence. And the natives ended up with the short end of the stick. An end so short that their culture and pride almost disappeared, drown under alcohol, tobacco, crimes, despair, even smallpox.

I have seen my share of clueless white people reciting some land acknowledgment. It typically goes like this: “”We gratefully acknowledge the Native Peoples on whose ancestral homelands we gather, as well as the diverse and vibrant Native communities who make their home here today” I think, crimes are something to silently repent about, not something to acknowledge often and gratefully. Sometimes, shutting up is pretty much the only decent thing to do. In that context, the Smithsonian museum of native Americans in Washington should be dismantled, burnt by the natives, and rebuild by them so that we see the reality of the genocide from their point of view (not from that of their oppressors).

Karl M Mon 14 Oct 11:41 PM

Thank you, Rick Morain

This story is even worse than I expected. I knew parts of it before, but not the grim entirety. I hope it is being taught in Iowa schools.

I also hope that the LITTLE HOUSE books by Laura Ingalls Wilder are not being presented to Iowa children in the same uncritical way in which they were presented to children when I was young. The mention of Indian Territory in this essay was a reminder that the Ingalls family were illegal squatters in that territory for a time during the years after they left Iowa. And those books contain examples of the common white attitudes toward “Indians” back then, awful attitudes that enabled the general awful history.

PrairieFan Wed 16 Oct 3:19 PM