After taking a closer look at the 2016 Iowa House election results, Kent R. Kroeger believes Iowa Democrats have reasons to worry but also reasons to be optimistic about their chances of taking back the chamber. You can contact the author at kentkroeger3@gmail.com.

The dataset used for the following analysis of 2016 Iowa House races with Democratic challengers or candidates for open seats can be found here: DATASET

When former U.S. Undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs Tara Sonenshine asked in her July 2016 Huffington Post essay, “Is 2016 the year of the woman?”, she can be forgiven if her underlying assumption was that the U.S. would be electing its first female president four months later.

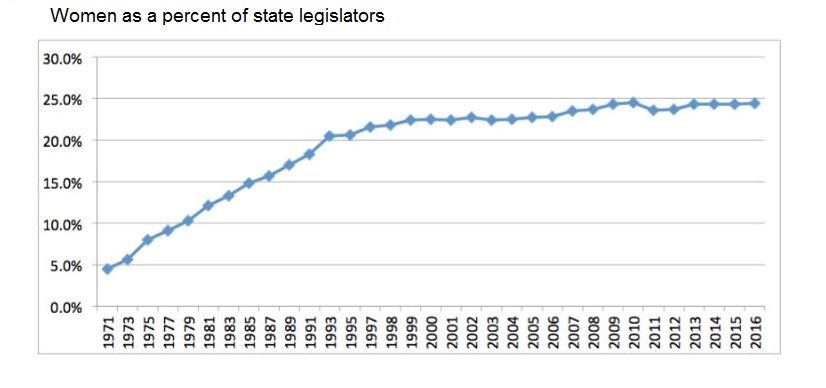

We know how that turned out. Yet, her question had a broader vision and was not dependent on the outcome of one presidential race in one country. The question springs from an emerging body of evidence that women may make for better politicians than men. Given that only 19 percent of U.S. congressional seats are currently held by women, it may seem ridiculous to ask such a question. And since 2000, the percentage of women in state legislatures has plateaued (see graph below). Nonetheless, looking across a longer time span, there is no question more and more women are running and winning elective office in this country.

So when I started to analyze the 2016 Iowa House races in an effort to develop a measure of “candidate quality” among the Iowa House candidates, I was looking for candidates’ attributes that correlated, all else equal, with higher vote shares. Since incumbency is such a dominant predictor of electoral success, I focused on Iowa House races with Democratic challengers or candidates for open seats. Lacking the advantages of incumbency, what factors regarding a candidate’s background and characteristics give them an advantage with voters? If the Democrats are going to regain control of the Iowa House, they will need to beat a few Republican incumbents. Unfortunately, over 90 percent of incumbents have won reelection in Iowa legislative races over the past 20 years.

The candidate gender effect: What is the existing evidence?

Most of the previous research on women politicians focuses on their productivity once elected to office. For example, a 2010 study by Sarah Anzia at Stanford University and Christopher Berry at the University of Chicago found that women legislators in the U.S. Congress generate 9 percent more discretionary spending in their home districts than do male legislators, independent of the legislator’s party and district’s characteristics. Women legislators also sponsor more bills and find more co-sponsors for the legislation they author. But these findings have been dubbed by some as the “Jackie Robinson effect” which argues that because of the inherent sexism of American political culture, a disproportionate percentage of women legislators are exceptionally gifted compared to their male counterparts.

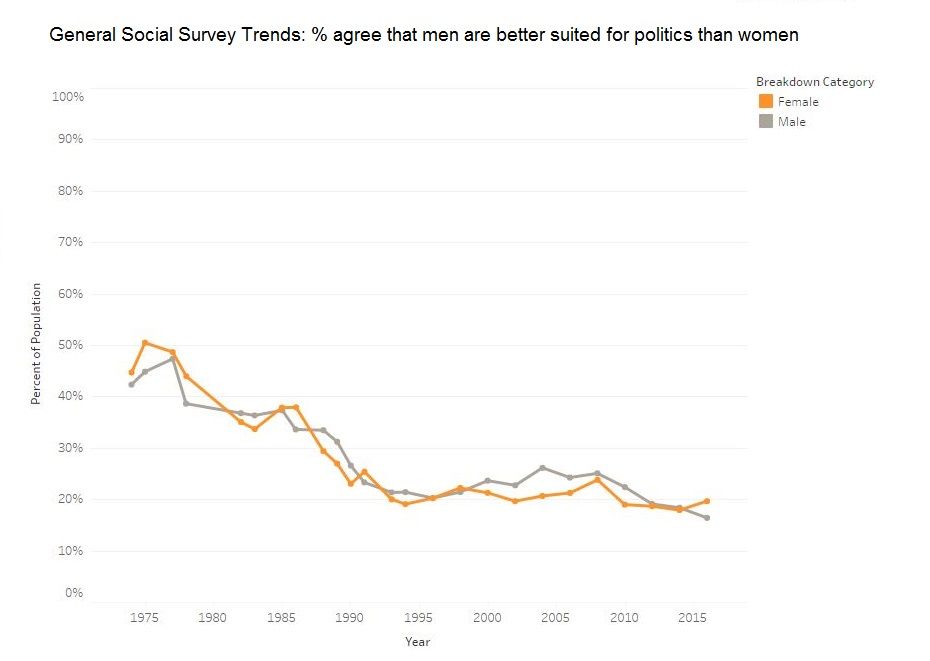

Other researchers, however, have found that public attitudes towards women candidates have improved substantially since the 1970s. According to the General Social Survey, in the early 1970s, over 40 percent of both men and women believed “men were better suited for political office than women.” By 2016, among both men and women, less than 20 percent held that belief (see chart below).

More pessimistically, the website Fivethirtyeight.com conducted a survey of registered voters in 2016 and found that, particularly among Republicans, there remains a large minority of people who prefer men over women when voting. In that survey, 29 percent of Republican women and 42 percent of Republican men said they would more likely vote for a man than a woman. That is not encouraging, but even that research fails to address the more direct question: In actual elections, have women candidates performed better than men after controlling for other factors that determine election outcomes (incumbency, economic conditions, partisanship, ideology, campaign events, etc.)?

Why did some Democratic challengers in the 2016 Iowa House elections do better than others?

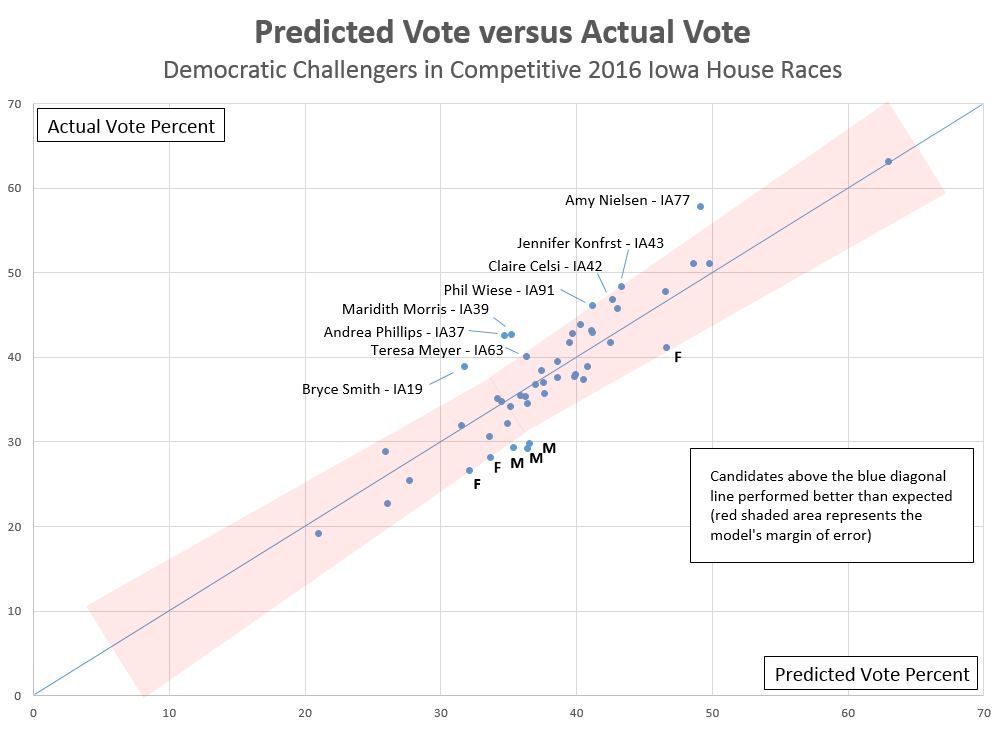

I had a personal interest in this question, having worked on my brother Gary Kroeger’s campaign in Iowa House district 60. But beyond that connection, I was also curious. Clearly, some Democratic challengers did better than others. Among the 48 Democratic candidates who were not incumbents in 2016, eight achieved a significantly higher percentage of the vote than expected (based upon the partisan makeup of the district).

But why? They weren’t necessarily better funded candidates. They weren’t all from urban districts. But there was one possible difference. Of the those eight Democrats, six were women (see graphic below). Considering that only 19 out of the 48 Democratic non-incumbents were women, this seemed significant, and, according to Fisher’s Exact Test, the gender effect was significant (p-value =0.045).

But, a simple statistical test doesn’t prove anything, especially given the small slice of data I was using for the analysis. Nonetheless, my curiosity compelled me to rule out other factors that could explain why a high percentage of the high performers were women.

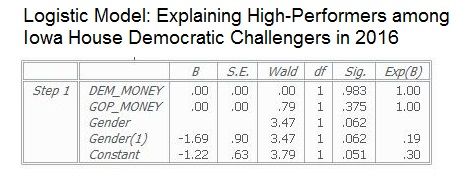

The most obvious variable to me was money. Perhaps these six Democratic women running against Republican incumbents were better funded than other Democratic challengers. Did the Iowa Democratic Party steer resources (monetary and non-monetary) to women candidates in order to fulfill the “year of the woman” narrative?

The data on money said, no. In the 48 races I analyzed, the amount of money spent by the high-performers and their opponents did not distinguish them from lower performing Democratic challengers (see Logistic model below). The variable that did remain close to significant was gender. Being a woman Democratic challenger was related to higher performance.

Other factors that still need to be considered are the quality of the Republican opponents, urban versus rural districts, the age of the candidates, and the possibility that toxicity of the presidential campaign, particularly with respect to sexism, may have driven a disproportionate number of conservative women to vote for Democratic women candidates. My dataset does not address these questions. Much more research is obviously needed to accept the conclusion that women (at least in 2016 Iowa House races) performed better than men.

If women are better candidates, why?

As I said, this dataset is too limited to make any broad generalizations. But I am not the only one asking this question, and others have already suggested reasons why women might be better politicians.

Campaign consultant Phil Van Treuren hypothesizes that women make better candidates because of natural communication skills, higher thresholds for stress, a better ability to make supporters and volunteers to feel appreciated, a lower likelihood of “skeletons in the closet,” and demographic advantages. I would also add that it’s possible women, when elected, are more effective legislators due to a higher propensity for cooperation, consensus-building, and problem-solving.

In the end, what does this all mean?

The issue is bigger than just gender. Having seen the electoral process in Iowa up close, I am distressed at the lack of vision and ingenuity among many Democratic leaders on candidate recruitment, training, and election assistance. The Iowa Democratic Party cannot afford to treat Iowa House elections as proving grounds for discovering new talent. If not for our own campaign’s self-financed polling in House district 60, we would have been flying blind going into the final weeks of the 2016 campaign. That is unacceptable in a modern state party operation.

But that “benign neglect” of its own non-incumbent Iowa House candidates is what I saw in 2016, and I see nothing yet under the new IDP’s leadership to suggest 2018 will be different.

I can’t repeat this fact often enough: Not a single Democratic challenger defeated a Republican incumbent in Iowa’s 2016 legislative races. I am reminded of author John C. Maxwell’s words — “Sometimes you win, sometimes you learn.” The Iowa Democrats did some serious learning in 2016.

And it is not hard to understand why challengers lose. Along with often living in Republican-leaning district, challengers don’t get as much financial support as do the party’s incumbents.

But the doctrinaire use of cost-benefit analyses in deciding which candidates receive IDP support reinforces the electoral system’s incumbency bias that, at this point, hurts the Democrats more than the Republicans.

Without a major strategy shift that brings formerly reliable Democratic voters back into the fold and persuades independents and weak Republicans that the Democrats best serve their interests, any electoral gains made in 2018 because of the Trump administration’s incompetence may be transitory.

An Iowa Democratic comeback will require persuasion. It’s a lost art on both sides of the aisle, but it never stopped being important. There are no short-cuts, and demographic changes won’t be as helpful to the IDP as they will be to Democrats in some other states.

And it is this need for persuasion where I believe women candidates may have an inherent advantage over men. After 30 years of studying political behavior and public opinion, the one constant I have found is that voters, after considering their party identification and ideological preferences, will vote for the candidate they trust and like. The empirical evidence is substantial that women are considered more trustworthy than men. That finding is as close to a physical law as you will find in social science.

So the IDP has a big challenge ahead. Along with reducing the gap in party registration in GOP-dominated districts and changing the party’s messaging in order to attract more independent voters, the IDP must do a better job at recruiting high-quality candidates. And once recruited, give them more up-front support (e.g., training in fundraising, media production and public speaking). That does not mean tilting the scales during the primary process. Quite the opposite: anyone interested in committing themselves to run for public office deserves support from their party. Regardless of whether there is a gender effect, how the Democrats assess and cultivate talent is inadequate and must improve.

In the end, it’s the message that will bring back electoral success, but without quality candidates, the message will never get through to voters. Does that mean recruiting more women candidates? I think it does.

About the author: Kent Kroeger is a writer and statistical consultant with over 30 years of experience measuring and analyzing public opinion for public and private sector clients. He holds a B.S. degree in Journalism/Political Science from The University of Iowa, and an M.A. in Quantitative Methods from Columbia University (New York, NY). He lives in Ewing, New Jersey with his wife and son.

Top image: Polk County Democratic women candidates for the Iowa legislature in 2016. Back row, from left: Claire Celsi, challenger in House district 42; Andrea Phillips, challenger in House district 37, Jennifer Konfrst, challenger in House district 43. Front row, from left: Miyoko Hikiji, challenger in Senate district 20; Maridith Morris, challenger in House district 39; Heather Matson, challenger in House district 38.

3 Comments

Women as trustworthy

There’s a separate trend that adds to the evidence that women are commonly seen as more trustworthy than men. Over the past forty years, more and more industries with public-image problems have been hiring women as their public-relations professionals and as the voices in their TV ads. I’m sure their consultants tell them that is smart.

I’ve had to face and fight my own double-standard bias that it’s worse to see a woman lying for an industry than to see a man doing the same. Ditto regarding conservative women in politics compared to conservative men.

PrairieFan Tue 30 May 9:04 AM

Democracy could use a few rivets, Rosie, and all the guys are drunk and stupid

So many possible responses to this question, aside from the immediate, “What kind of sexist BS is this?” snark. My stats professor failed to show up for my college final exam, which is probably a good thing, as I already had sensed I lacked a full grasp of all the necessary key concepts and methods. So I’ll just go here with a spontaneous intuitive guess. Better candidates? Probably no, because of tendencies towards less aggression, less lying, more empathy. Better legislators? Hell yes, because of tendencies towards less aggression, less lying, more empathy, better organizing skills, better (honest) communication skills. Of course there are extraordinary outliers in every flavor, color, size, shape, and mind-set imaginable; enough for anyone to argue a point and make the pointy-headed stats genius look like an idiot. (I’ve pounded sand mentally for a year trying to figure out “What the hell is WRONG with you, Joni, supporting this vulgarian career criminal?”) In any event, IMHO, on the whole, there is more than one good reason for the “fairer sex” adage. We need more of them NOW to clean up the greedy testosterone infused societal damage done by boys being not at all well behaved boys. Some highly intelligent and honest guys (or, for God’s sake, at least just honest) can be of enormous help as well along the way, but the supply seems to be a bit low at the moment in our political arenas. (By the way, was Sally Yates great or what? So it need not be just politicians.)

Fly_Fly__Fly_Away Tue 30 May 2:34 PM

Nice piece, I have more data to add.

Kent,

I appreciate the work you’ve done and have downloaded the data set. I’m adding some social and economic data to the set and will work on a model later in the week. I was wondering if you might have a code book to go along with the data. I’d like to see the descriptions of your variables.

Thank you,

Scott Thompson

sathompson Sat 3 Jun 5:48 PM