A 2008 amendment to the Iowa Constitution became a matter of debate in Griffin v Pate, the major voting rights case before the Iowa Supreme Court. The amendment changed Article II, Section 5, which as adopted in 1857 read, “No idiot, or insane person, or person convicted of any infamous crime, shall be entitled to the privilege of an elector.” The same section now reads, “A person adjudged mentally incompetent to vote or a person convicted of any infamous crime shall not be entitled to the privilege of an elector.”

Two of the seven Supreme Court justices have previously held that when approving the 2008 constitutional amendment, the legislature “ratified its own existing interpretation of that provision under which infamous crime meant a felony.” In its brief for the Iowa Supreme Court on behalf of defendants in Griffin, the Iowa Attorney General’s Office carried forward that claim: “By failing to alter the Infamous Crime Clause when other portions of Article II, section 5 were amended, the Legislature and the public ratified the definition of infamous crime as all felonies under state and federal law.” During the March 30 Supreme Court hearing on Griffin v. Pate, Solicitor General Jeffrey Thompson likewise argued “the simple answer here” is the 2008 constitutional amendment was “passed twice by the General Assembly, adopted by the people of Iowa, in the context of a legal system and historical cases and practices that said felonies are the line.”

My curiosity piqued, I decided to look into the legislative intent behind the 2008 constitutional amendment. What I found does not support the view that Iowa lawmakers envisioned “infamous crime” as synonymous with “felony” or intended to ratify such an interpretation when voting to remove offensive language from the state constitution.

WHY IT MATTERS

Kelli Jo Griffin’s lawsuit challenging Iowa’s voter disenfranchisement policy grew out of a plurality ruling in a 2014 ballot access case, Chiodo v. Section 43.24 Panel. Three of the seven justices held that Tony Bisignano was eligible to run for the Iowa Senate despite his prior conviction on an aggravated misdemeanor charge. The plurality opinion by Chief Justice Mark Cady, joined by Justices Daryl Hecht and Bruce Zager, further suggested that contrary to a 1994 state law, not all felony offenses should be considered “infamous crimes.”

A concurring opinion by Justice Edward Mansfield, joined by Justice Thomas Waterman, held that Bisignano could run for the Senate, but argued that the high court should defer to the 1994 law defining all felonies as infamous crimes. Mansfield’s special concurrence in Chiodo noted, “Iowa amended and reenacted its constitutional clause disenfranchising persons convicted of infamous crimes in 2008.”

Furthermore, in 1994, the legislature enacted the current law that specifically defines “infamous crime” for voting and elective office purposes to mean a felony. See 1994 Iowa Acts ch. 1180, § 1 (codified at Iowa Code § 39.3(8) (1995)). This takes on particular significance, in my view, because our general assembly, in 2006 and 2007, and the voters of our state, in 2008, repealed the existing article II, section 5 and approved a new version. See 2006 Iowa Acts ch. 1188, § 1; 2007 Iowa Acts ch. 223, § 1.

The previous version of article II, section 5, dating back to 1857, read, “No idiot, or insane person, or person convicted of any infamous crime, shall be entitled to the privilege of an elector.” Iowa Const. art. II, § 5 (1857). The new version reads, “A person adjudged mentally incompetent to vote or a person convicted of any infamous crime shall not be entitled to the privilege of an elector.” Iowa Const. art. II, § 5 (amended 2008).

It is clear that the legislature’s specific purpose in 2006 and 2007 was to remove offensive and outdated language from article II, section 5. However, the legislature knew it was keeping in place the prohibition on voting by those convicted of infamous crimes and knew that its own laws at that time defined infamous crime as a felony. See Iowa Code § 39.3(8) (2007). It would be absurd to suggest the legislature intended to approve a constitutional amendment that struck down its own law—Iowa Code section 39.3(8). Therefore, when the legislature twice voted to repeal and replace the existing article II, section 5 with a new version, I believe it ratified its own existing interpretation of that provision under which infamous crime meant a felony.

We have long adhered to this principle as it applies to statutory amendments. “When the legislature amends some parts of a statute following a recent interpretation, but leaves others intact, this ‘may indicate approval of interpretations pertaining to the unchanged and unaffected parts of the law.’ ” State v. Sanford, 814 N.W.2d 611, 619 (Iowa 2012) (quoting 2B Norman J. Singer & J.D. Shambie Singer, Statutes and Statutory Construction § 49:10, at 144 (7th ed. 2008)); see also Jenney v. Iowa Dist. Ct., 456 N.W.2d 921, 923 (Iowa 1990); State ex rel. Iowa Dep’t of Health v. Van Wyk, 320 N.W.2d 599, 604 (Iowa 1982). Logic dictates that this rule should apply equally to constitutional amendments.

A decision of the Kansas Supreme Court illustrates this principle. See In re Cent. Ill. Pub. Servs. Co., 78 P.3d 419 (Kan. 2003). […] In concluding that this narrow statutory definition should apply, the court indicated among other things that the constitutional amendment should be construed consistently with “the statutes in existence at the time the . . . amendment was proposed and adopted.” Id. at 426. Here too, where article II, section 5 was repealed and reenacted in 2006–2008, I believe the term “infamous crime” should be construed consistent with the statute in existence at that time, Iowa Code § 39.3(8). See also Cal. Motor Express v. State Bd. of Equalization, 283 P.2d 1063, 1065 (Cal. Ct. App. 1955) (finding that reenactment of a constitutional provision “which has a meaning well established by administrative construction is persuasive that the intent was to continue the same construction previously recognized and applied”); Wakem v. Inhabitants of Town of Van Buren, 15 A.2d 873, 875–76 (Me. 1940) (“It is a general rule that a reenactment, in substantially the same language, of a constitutional provision which had been previously construed and explained by the court, carries with it the same meaning previously attributed by the court to the earlier provision, in the absence of anything to indicate that a different meaning was intended.”); Bodie v. Pollock, 195 N.W. 457, 458 (Neb. 1923) (“It is well settled in many, if not most, of the jurisdictions of the country that, where a construction of constitutional provisions has been adopted and a constitutional convention thereafter re-enacts such provisions, it re-enacts not only the language of the provisions but the construction which has attached to the same.”).

It was also no secret that Iowa law forbid voting by convicted felons when the proposed amendment went before the public at the 2008 general election.

The Attorney General’s Office articulated the same argument in its final brief on Griffin v Pate in the Iowa Supreme Court:

The district court correctly determined that all felonies are infamous crimes because (1) the 2008 Amendment to Article II, section 5 ratified the statutory definition of infamous crime, and (2) for over one hundred and fifty years this Court has found that all felonies are infamous crimes.

1. The 2008 Amendment to Article II, Section 5 Ratified the Statutory Definition of Infamous Crime. Throughout this litigation, Petitioner has focused on the meaning of the Infamous Crime Clause as ratified in 1857. As pointed out by the special concurrence in Chiodo, the constitutional provision at issue in this case was actually enacted in 2008 not 1857. Chiodo v. Section 43.24 Panel, 846 N.W.2d 845, 861–62 (Iowa 2014) (Mansfield, J., specially concurring). In 2006 and 2007, the General Assembly voted to amend Article II, section 5 of the Iowa Constitution. See 2006 Iowa Acts ch. 1188, § 1, 2007 Iowa Acts ch. 223, § 1. That amendment was ratified in 2008 by popular vote.

Admittedly, that amendment was intended to remove the offensive and outdated “idiot” language from the Iowa Constitution and did not alter the Infamous Crime Clause. Nevertheless, both the General Assembly and voters had the opportunity to amend or clarify the infamous crime language and chose not to do so. Instead both the General Assembly and the people of Iowa readopted the Infamous Crime Clause in its entirety. See State v. Sanford, 814 N.W.2d 611, 619 (Iowa 2012) (“When the legislature amends some parts of a statute following a recent interpretation, but leaves others intact, this ‘may indicate approval of interpretations pertaining to the unchanged and unaffected parts of the law.'”) (quoting 2B Norman J. Singer & J.D. Shambie Singer, Statutes and Statutory Construction § 49.10, at 144 (7th ed. 2008)).

The historical and legal context of the 2008 ratification are instructive. In 1994, the Iowa General Assembly enacted a statutory definition of infamous crime. 1994 Iowa Acts, ch. 1169, § 7, ch. 1180, § 1. Iowa Code section 39.3(8) defines “infamous crime” as any felony under Iowa or federal law. Thus, in, 2007, and 2008 when the Infamous Crimes Clause was ratified infamous crimes were defined as felonies.

The statutory definition of infamous crime was reiterated by the Legislature when it revamped election crimes in the early 2000s. In a rare expression of legislative intent, the General Assembly noted:

It is the intent of the general assembly that offenses with the greatest potential to affect the election process be vigorously prosecuted and strong punishment meted out through the imposition of felony sanctions which, as a consequence, remove the voting rights of the offenders. Other offenses are still considered serious, but based on the factual context in which they arise, they may not rise to the level of offenses to which felony penalties attach.

Iowa Code § 39A.1(2), 2002 Acts, ch 1071, § 1.

Both the Legislature and the public are presumed to know the law. By failing to alter the Infamous Crime Clause when other portions of Article II, section 5 were amended, the Legislature and the public ratified the definition of infamous crime as all felonies under state and federal law. Not only is this answer supported by this Court’s longstanding rules of statutory interpretation, but it also most accurately reflects the evolving nature of constitutional jurisprudence.

Representing the state in the March 30 oral arguments, Solicitor General Thompson touched on this point in dialogue with several justices. My transcript of the relevant portion, beginning around the 57:35 mark of this video:

Thompson: As you know from our brief, we think Justice Mansfield and Justice Waterman got it right [in Chiodo]. That frankly, the simple answer here–and sometimes simple answers don’t feel right–is that this is a 2008 constitutional provision, passed twice by the General Assembly, adopted by the people of Iowa, in the context of a legal system and historical cases and practices that said felonies are the line.

Chief Justice Mark Cady: Do you think in 2008 the people of Iowa seriously considered the issue that we’re here considering today?

Thompson: I don’t. But that’s not, that’s not what I am suggesting. Because your, your standards that we’ve cited with regard to this issue–State v. Sanford is one of the most recent decisions in this–is it’s not dispositive, it’s just a presumption. It’s a presumption, it’s kind of constructive notice, right? We’re not saying they voted it, or even that, that Justice Wig–

Justice Edward Mansfield: You think in 1857, when the 1857 constitution was ratified that the voters were paying attention?

Thompson: No! In fact, you just established with Mr. [Alan] Ostergren [who represented the Iowa County Attorneys Association] that they didn’t talk about it. So, it’s a legal presumption that, that says that when you construe something, your–

Cady: And is, and is the intent just a myth?

Thompson: Absolutely not. But, but–

Justice David Wiggins: If you look at, if you look at when they did that, though, they took “imbecile” out of maybe five or ten other sections of the code. They cleaned it up that time–they did it by statute, because they didn’t need a constitutional amendment to do it.

Thompson: There is no question, we are not arguing that it was something they specifically–we’re saying that it is one of your canons of construction. I mean, in Sanford you applied it in a criminal case, and, and it took away someone’s liberty, right? So I mean we don’t do it lightly, but it’s–

Wiggins: Couldn’t we find that the intent was just to clean up the code, and to clean up the constitution, not to change the meaning of it? Because if you read–I haven’t read it, but I’m sure if you read the explanation, to the change from “imbecile” to mentally, mentally whatever they have in the code, I can’t get the exact words, you will see that was the purpose of them doing it.

Thompson: OK, but, but–and I don’t disagree with that. What I’m saying is, it didn’t–I don’t think it changed the meaning. It just ratified a meaning that was already in existence in the law and that is consistent with this court’s previous findings [….]

And again, it’s a presumption. So you don’t have to–if it’s inconsistent with the law, or clearly erroneous, you don’t have to accept it. My point is that–

Cady: How should we apply that presumption? Does it apply in this case? [….] So it seems like, if we apply this presumption that you’re asking us to apply in 2008, shouldn’t it be consistent with our democratic process, that there was a “clamor of debate” that went in to, to express, a new understanding of what we thought of the term “infamous crime”? And not just some technical ratification?

Thompson: I, I don’t disagree with that. I mean, I think that that would be aspirational. I don’t think that’s what your cases say. I, I think your cases say that, that there’s a built-in presumption that if something is changed in a statutory provision–granted, in Iowa you’ve not done this in the context of the constitution, so I’m hearing you say, is this different? And I’m saying, well, it probably is, it could be. But if you apply the presumption for legislative enactments, then it’s a presumption. And so, I guess what I’m, what I’m conceding to you, Chief Justice, is that we are in the context of a constitutional provision. I think Justice Mansfield in his concurrence [to Chiodo] cited some other states’ cases where they apply the same presumption to a constitutional provision […].

I’m not an attorney, and this blog isn’t a court of law. So I’m happily not bound by any precedent telling me what to presume about lawmakers’ mindset when they changed the words “idiot” and “insane person,” but not “infamous crime.”

THREE FAILED ATTEMPTS TO REDEFINE “DISQUALIFIED PERSONS”

I turned first to Iowa Senate President Pam Jochum. Having raised a daughter with intellectual disabilities, she became the leading advocate for removing the word “idiot” from the state constitution after being elected to the Iowa House. During a telephone interview, I asked Jochum whether lawmakers ever considered revising the phrase “infamous crime” while changing other language in the same section. To my surprise, she said “the original amendment that we had proposed when I was serving in the House was also [to] address infamous crime.” As she recalled, the amendment got through the House several times, but repeatedly got stuck in the Iowa Senate: “So in order to get something changed in the constitution, we had to drop–I don’t remember what the wording was, but I know we attempted to address ‘infamous crime’ in our original, in some of the original constitutional amendments that we had drafted.”

Jochum added that she had worked on the amendment with State Representatives Betty Grundberg and Mona Martin, who chaired the House State Government Committee at the time. Republicans Grundberg and Martin shared Jochum’s interest in the issue, since Grundberg had a close relative who suffered from mental illness, and Martin was active with the League of Women Voters.

I had no idea this effort to amend the constitution began so long ago. (Grundberg lost her re-election bid to Democrat Jo Oldson in 2002.) Jochum: “I’m telling you, that’s how far back we started trying to amend the constitution to get rid of ‘idiot’ and ‘insane,’ and our original stuff included dealing with the ‘infamous crime’ section of the constitution as well. We passed stuff. We’d send it over to the Senate, and they wouldn’t take it up.”

The way Jochum remembers the story, “We understood that we were having problems with that ‘infamous crime’ piece of the constitution.” But some senators preferred to leave “infamous crime” alone, because they hoped someday to revise Iowa Code to define the term more narrowly, such as only covering class A felonies, or class A and B felonies.

Jochum couldn’t say exactly how she and her colleagues intended to rewrite the “infamous crime” language, but she recalled trying to pass the amendment “three different sessions in a row,” without success.

There were three failed attempts. However, the legislative record indicates that the amendments didn’t die in the Iowa Senate. Rather, they never made it out of an Iowa House committee. At this writing, I cannot confirm whether the amendments became non-starters in the House after back-channel conversations with state senators suggested the measure was doomed in the upper chamber. Keith Kreiman, a Democrat who served on the Senate Judiciary Committee during this period, told me by phone today he does not remember any move to change the words “infamous crime” coming up in the Iowa Senate.

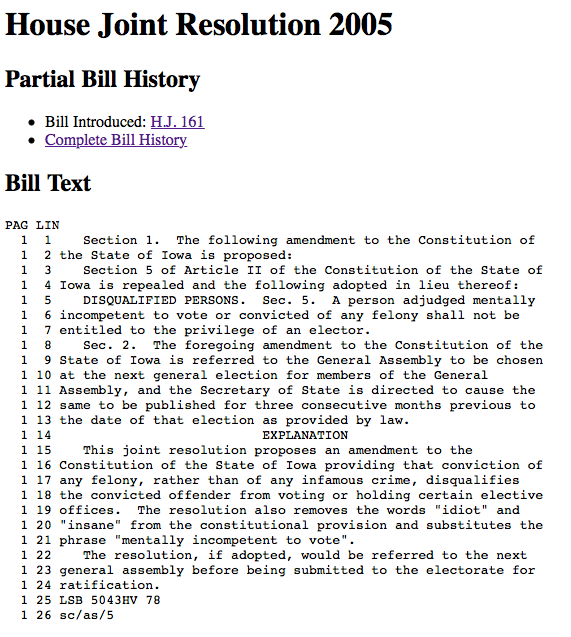

In any event, Martin chaired the House State Government Committee when that committee introduced House Joint Resolution 2005 in February 2000. In telephone interviews this week, neither Martin nor Grundberg recalled any discussion about changing “infamous crime”–only that they had strongly supported Jochum’s commitment to remove what Martin called “archaic and insensitive” language from the constitution. As you can see from the text, this legislation would also have revised the phrase “person convicted of any infamous crime” to “person convicted of any felony.”

The bill history shows that House Joint Resolution 2005 was never assigned to a subcommittee. Martin could not remember why the legislation didn’t go forward. She referred me to Jochum, who, she said, would have been privy to more conversations about the issue.

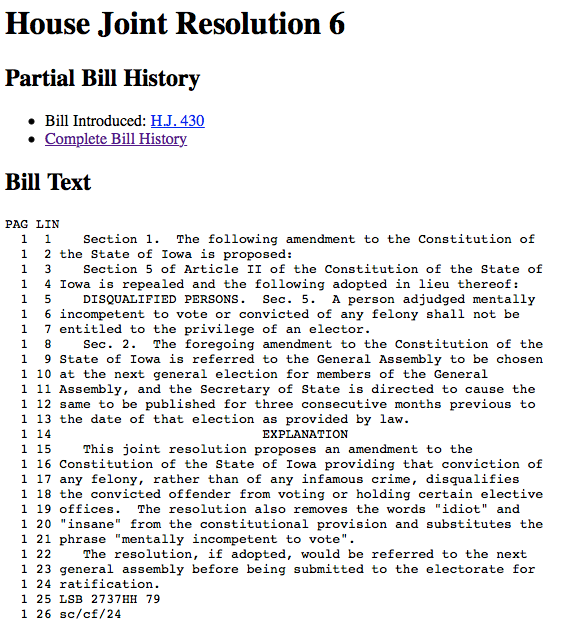

During the 2001 legislative session, Jochum introduced House Joint Resolution 6, with an identical text:

The House Judiciary Committee referred the amendment to a subcommittee, where it saw no further action.

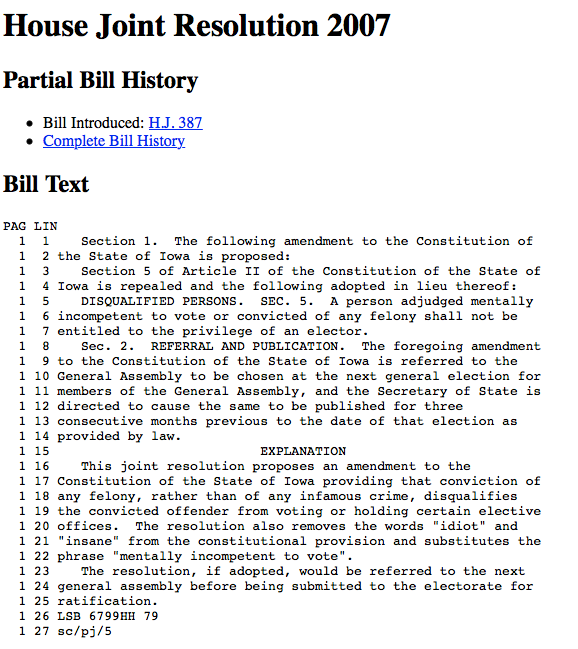

In early 2002, then House Majority Leader Chris Rants and House Minority Leader Dick Myers jointly introduced House Joint Resolution 2007, sending the strongest possible signal of bipartisan support for this measure. Again, the amendment would have replaced “idiot” and “insane person” with “mentally incompetent” and would have replaced “infamous crime” with “felony.”

By now, Janet Metcalf chaired the State Government Committee. She assigned the constitutional amendment to a subcommittee including Jochum, herself, and fellow Republican Chuck Gipp, who is now director of the Iowa Department of Natural Resources. According to the legislative record, the subcommittee never acted on the bill.

Gipp told me by phone, “No, I don’t recall as to why that bill didn’t move at that particular time. I don’t know if it was late in the session, or whatever it was, but I don’t even recall that.” (The joint resolution was referred to subcommittee in February, not late in the session.) Gipp also didn’t remember any conversations about changing “infamous crime” to “felony.”

Metcalf similarly didn’t recall any discussion about the “infamous crime” provision. She said during our phone interview, “I do remember wanting to get rid of the word idiot. That was offensive to me.” Like the other Republicans I have spoken with, Metcalf confirmed that Jochum’s proposal was uncontroversial: “All of us objected to the word ‘idiot.’ […] The focus was on changing that definition.”

I turned to Rants, who commented apologetically after hearing the reason for my call, “I don’t have any recollection. I’m sorry, I don’t even remember introducing it […] I remember the discussion about that [removing the word idiot] and why we needed to do that. I don’t remember the infamous crimes piece.”

SUCCESS AFTER DROPPING REVISION TO “INFAMOUS CRIME”

As Jochum recounted, the constitutional amendment finally made progress after House members agreed to let “infamous crime” stand unchanged.

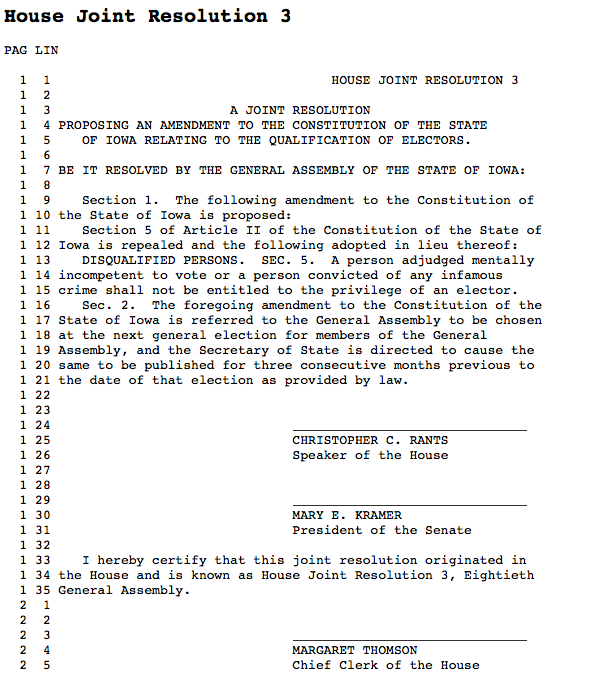

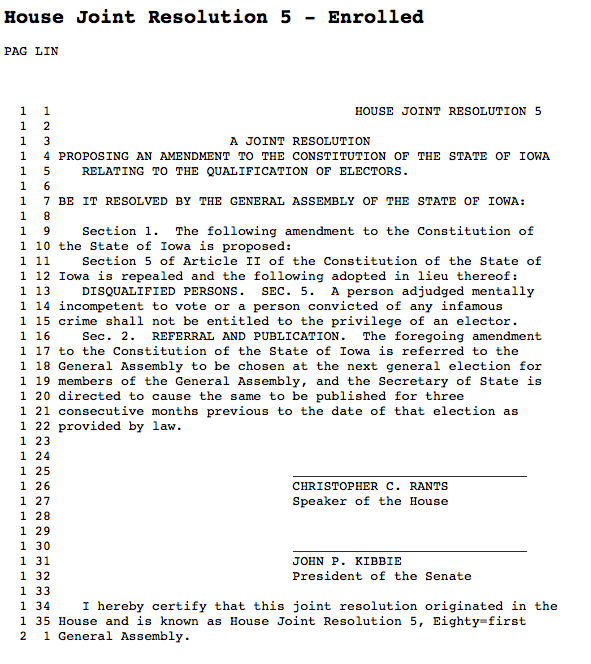

Here’s the full text of House Joint Resolution 3, which both chambers of the legislature approved unanimously in 2003.

Same story for House Joint Resolution 5: unanimous passage in 2006.

Under Article X of the Iowa Constitution, a constitutional amendment is submitted to all eligible Iowa voters after approval by both chambers of two consecutively elected legislatures. In theory, the amendment removing the words “idiot” and “insane person” should have been on the 2006 general election ballot after passing the 80th General Assembly in 2003 and the 81st General Assembly in 2006.

Two missteps derailed what should have been routine procedure. Charlotte Eby told this part of the story in the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier on February 8, 2006. I don’t have a working link to this piece, but the Courier’s Christinia Crippes provided the text. Excerpt:

A mistake by Secretary of State Chet Culver and a top legislative official means voters will not have a chance this fall to strike outdated descriptions in Iowa’s constitution referring to those who are mentally incompetent as an “idiot” or “insane.” […]

But a failure to properly publish notice of the proposed changes in 2004 means it cannot be on the ballot for voters to consider this fall and will be pushed back until 2008. […]

After the Legislature approved the changes in 2003, Culver’s office had been responsible for publishing notice in the newspaper the following year. That never happened.

Chief House Clerk Margaret Thomson said the amendment also was supposed to be published by her office in its entirety in the House Journal, an official record of proceedings in the Iowa House. The amendment was published only in part.

“We’re really embarrassed about it,” Thomson said of the error. The same mistake was not made in the Senate.

Sure enough, the House Journal for February 18, 2003 shows that House Joint Resolution 3 passed but does not reproduce the full text of the amendment. In contrast, the Senate Journal for March 26 of that year includes the full text.

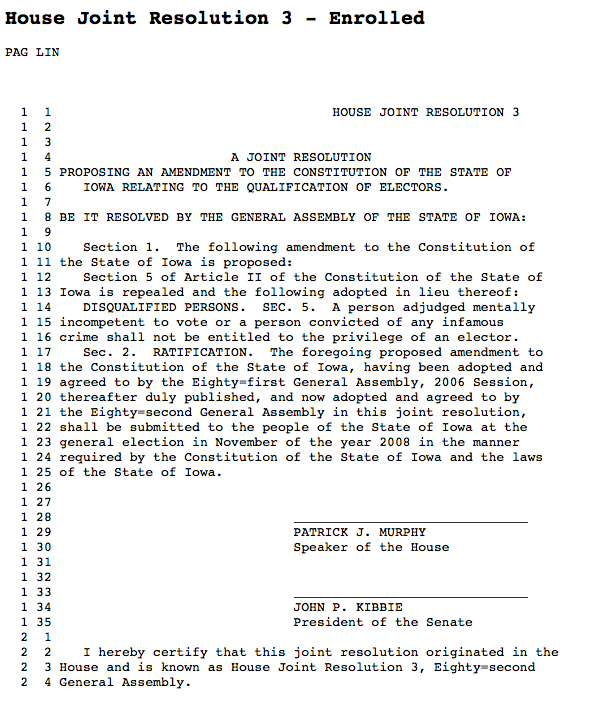

Consequently, lawmakers started the process over when approving House Joint Resolution 5 unanimously in 2006. The newly-elected 82nd General Assembly took up the same provision, now called House Joint Resolution 3, early in 2007.

Again, lawmakers in both chambers approved the amendment unanimously.

No doubt the errors that forced a third vote on this constitutional amendment were honest mistakes. Still, it’s frightening to think a staffer with malign intent could subvert the legislature’s intention to amend the constitution by “forgetting” to publish the text properly. Jochum had no trouble convincing her colleagues to take this measure up in 2007, but imagine doing heavy lifting to get a controversial amendment through both chambers twice, only to learn you had to do it again after another general election, which might significantly change the composition of the legislature.

Back to the main point of this post: what the evidence suggests about lawmakers’ intent when they re-enacted the constitutional provision on qualifications of electors.

PRESUMPTION VS. THE RECORD

Justice Mansfield posited in his special concurrence to Chiodo, “when the legislature twice voted to repeal and replace the existing article II, section 5 with a new version, I believe it ratified its own existing interpretation of that provision under which infamous crime meant a felony.”

The record tells a different story. Three times, Iowa lawmakers had the chance to state explicitly that citizens convicted of any felony would be disqualified as electors. Three times, that constitutional amendment did not advance.

The record further shows that a proposed amendment identical in every respect but one (it did not change “infamous crime” to “felony”) passed without a single dissenting vote–once, twice, three times, due to the procedural hiccup described above.

The Iowa Attorney General’s Office asserted in its brief to the high court, “both the General Assembly and voters had the opportunity to amend or clarify the infamous crime language and chose not to do so. Instead both the General Assembly and the people of Iowa readopted the Infamous Crime Clause in its entirety. […] Both the Legislature and the public are presumed to know the law. By failing to alter the Infamous Crime Clause when other portions of Article II, section 5 were amended, the Legislature and the public ratified the definition of infamous crime as all felonies under state and federal law.”

The opposite is closer to the truth: by declining to revise Article II, section 5 to read that a “person convicted of any felony shall not be entitled to the privilege of an elector,” state lawmakers indicated they did not want to enshrine in the Iowa Constitution the idea that all felonies justify depriving citizens of their voting rights.

As for the public, the infamous crime angle clearly was not salient for voters who approved this amendment in 2008. Media coverage overwhelmingly depicted the measure as being solely about removing obsolete references to people with intellectual disabilities.

Solicitor General Thompson acknowledged during his Iowa Supreme Court appearance last week, “sometimes simple answers don’t feel right.” In this case, his simple answer doesn’t feel right because it isn’t right. Lawmakers and the people of Iowa could have approved new language for the constitution, declaring all felonies grounds to revoke voting rights. They did not.

3 Comments

Different Conclusion

Great piece! Terrific job of recalling history. Demonstrates how difficult it is to determine what was going on in the heads of the Founders when lawmakers have trouble recollecting what happened just 10 or 15 years ago. On first pass, I wonder if you don’t have it backwards. That is to say, one theory suggests they left “infamous crime” in place because they wanted to retain legislative authority to narrow its definition in the future. I’m not sure that’s the same thing as retaining the language because they decidedly believed the current codification was at odds with the language in the Constitution. Seems to me, it almost enhances the argument that legislators believed this language was of a type that accorded the legislature some flexibility to codify what it means….including, the flexibility to define the term to mean “all felonies.” I don’t particularly like my conclusion, but having a hard time drawing a different one.

jonmuller Thu 7 Apr 12:20 PM

thanks

I didn’t mean to suggest that they believed the 1994 law was unconstitutionally broad (though I do think it was).

Most of the lawmakers don’t seem to have been thinking about the infamous crimes language at all. But assuming Pam Jochum’s recollection is accurate, and some wanted to preserve the legislature’s ability to define infamous crimes, it still suggests to me that they did not take for granted that “infamous crime” would necessarily encompass all felonies.

Several of the Supreme Court justices do not accept the legislature’s authority to define terms in the constitution, period. It’s not surprising that lawmakers would disagree and would see it as their role to define “infamous crimes” however they like.

desmoinesdem Thu 7 Apr 2:33 PM

The opposite is closer!

You got that right. Nice work. I hope the court takes judicial notice, as they say.

iowavoter Thu 7 Apr 2:18 PM