Herb Strentz was dean of the Drake School of Journalism from 1975 to 1988 and professor there until retirement in 2004. He was executive secretary of the Iowa Freedom of Information Council from its founding in 1976 to 2000.

Once upon a time—as fairy tales begin—a Democratic president and a former Republican president became friends and, despite political differences, worked together to save millions of lives around the world.

Not only that: although the Republican was wealthy, he didn’t care if he lost his fortune in trying to feed the starving.

The Democratic president was kind of poor. But after he left office, he turned down great big salaries, even though he could have simply attended corporate board meetings and said not a word.

Surprise! This is not a fairy tale at all.

It is a story about the late-blooming friendship of Herbert Hoover (1874-1964) and Harry Truman (1884-1972). Some called them “the odd couple.”

Here’s their story. I posted a somewhat different take at Bleeding Heartland in January, when Iowa politics appeared to be awful. Things are even worse now, and the story bears repeating.

Money’s not the question

Let’s begin with the money bit.

By the time he was 40, Hoover was wealthy, an engineering graduate of Stanford University, whose work on gold mines around the world gave him the nickname “doctor of sick mines.”

Aware of Hoover’s mining reputation, Belgians pleaded with him in 1914 to help their people on the verge of starvation. Hoover knew saying ”Yes” would put his personal life, his business, and his fortune at risk.

Over morning coffee, he told a friend: “Well, let the fortune go to Hell.” He aided the Belgians and other Europeans before and after World Wars I and II.

The fortune did not “go to hell.” After his presidency, Hoover lived at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City and had a home on the Stanford University campus.

On the other hand, when Truman left the presidency in 1953, he and Bess Truman took the train—not to the Waldorf, but to his mother-in-law’s home in Independence, Missouri. He had no Secret Service aid and no funds for an office or secretary. His army pension was $112.56 a month. (That works out to $1,087.34 in today’s dollars.)

Yet, when offered high-paying corporate board positions, Truman declined: “You don’t want me. You want the office of the President …that doesn’t belong to me…It belongs to the American people and it’s not for sale.”

No six-figure board salary or speaker’s fee for Truman.

These and other stories are worth recalling in 2023 because we’re in the centennial years, 1921-28, of Hoover’s service as the nation’s best-ever secretary of commerce.

Why “best-ever”? In what had been a trivial cabinet position, Hoover forced some sense upon the chaotic nature of the emerging broadcast and aviation industries. Seeking “efficiency, standardization and elimination of waste,” Commerce Secretary Hoover bought uniformity to plumbing and electrical fixtures in American homes, and in milk bottles, bricks, screw threads and lots of other weights and measures that we take for granted today.

1948 also marks the 75th anniversary of some of President Truman’s greatest accomplishments: The Berlin Airlift, the Marshall Plan, desegregation of the nation’s armed forces, recognition of the nation of Israel and, oh yeah, election as president.

Different roots and routes to becoming “the odd couple”

Born in West Branch, Iowa, Hoover was orphaned at a young age. His father died when Herbert was 6 and his mother when he was 10. The extended family had a measure of wealth. An uncle in Oregon took Herbert in; seven years later, he enrolled at Stanford.

Soon after graduation, Hoover found work with the British company Bewick Moreing. As noted above, he was quite a success. He established his own international company, which he ran from 1908 until retirement from mining in 1914.

A life of public service followed. The U.S. ambassador to England, Walter Hines Page, asked Hoover to help return 120,000 American tourists from Europe back to the U.S. at the onset of World War I. President Woodrow Wilson later appointed Hoover as U.S. Food Administrator during U.S. involvement in the war, then as director of the American Relief Administration at war’s end.

As for Truman, while his family was poor, he was not an orphan.

His father died when Harry was 30; his mother when he was president and 63. The family farmed in Grandview, Missouri, “in the sticks” outside Independence. His ambition to go to West Point was blocked by poor eyesight. He briefly attended a commercial college and a law school, but family needs brought him back to farming. He was well-read, self-schooled when ill in childhood.

After his World War I service in France commanding an artillery unit, Truman and his friend Eddie Jacobson opened a men’s clothing store in Independence in 1919. After a promising start, the store failed and was closed in 1922.

Truman refused to declare bankruptcy and over the years paid back his creditors.

That same year, he got into politics and was elected a Jackson County judge (like an Iowa county supervisor). He was involved with the Pendergast political machine in Kansas City and Jackson County, eventually being elected U.S. Senator in 1934. He was re-elected in 1940 despite expectations he would at best finish second in a field of three.

Bookend presidents to Franklin Delano Roosevelt

For Hoover, the likelihood of being elected president was pretty much a straight-line thing—from his success in management to his public service and his accomplishments as secretary of commerce. His 1928 opponent, New York Governor Al Smith was a Roman Catholic, a vote-getting bonus for Hoover just as it was a hindrance for the election of President John F. Kennedy, 32 years later.

People always had high expectations for Hoover, and he met or exceeded them, until the Great Depression hit in October 1929, a mere eight months into his presidency. (Back then, presidents were inaugurated in March, not January.) Democrats, the news media, and the public largely blamed Hoover for that for the rest of his life. The GOP had no warm welcomes.

For Truman, becoming president was anything but predictable. His reelection to the Senate in 1940 probably was more of a stunner than his election as president in 1948 against Republican Gov. Thomas Dewey, Progressive Henry Wallace and Dixiecrat Senator Strom Thurmond.

But there Hoover and Truman were, bookend presidents to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. FDR disdained Hoover and mostly ignored Vice President Truman.

FDR was volumes of politics himself and did not treat mere bookends well.

The day of Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, and the nation’s direct involvement in World War II, Hoover let FDR know he was available and anxious to serve the nation in any way he could. FDR never responded.

More than that, Roosevelt discussed with Bernard Baruch—who managed U.S. economic mobilization for President Wilson in WWI—how to best organize the home front for victory. Baruch said the best man for such an effort was Herbert Hoover.

FDR’s response: “I’m not Jesus Christ. I’m not raising him from the dead.”

As for Truman, he would serve as vice president only from the inauguration, January 20, 1945, to FDR’s death on April 12. In those 82 days, Truman had met with the president perhaps once, for a photo op.

We all could use such “bookends”

Undaunted by political party lines or FDR’s brushoff, Hoover again offered his services to President Truman and the nation. Truman accepted the offer.

Reflecting on that opening to their friendship, Hoover wrote to Truman in 1962:

Yours has been a friendship which has reached deeper into my life than you know. I gave up a successful profession in 1914 to enter public service. I served through the First World War and after for about 18 years. When the attack on Pearl Harbor came, I at once supported the President and offered to serve in any useful capacity. Because of my various experiences…I thought my service might again be useful, however there was no response… When you came to the White House, within a month you opened the door to me to the only profession I know, public service, and you undid some disgraceful action that had been taken in prior years.

When they met in the White House, Truman’s agenda was to talk with Hoover about dealing with war-induced, worldwide food problems. At age 71, Hoover accepted that challenge and within months traveled more than 51,000 miles through 38 countries to determine what should be done. He and Truman then developed food relief programs and hammered out international agreements to save the lives of millions. Some suggest hundreds of millions.

That was one happy ending in our tale. Others included their occasional meetings and correspondence over the years, and the dedications of the Truman Library and Museum in Independence July 16, 1957 and the Hoover Library and Museum in West Branch on August 10, 1962. (Both are just a two- or three-hour drive from Des Moines.)

Six days before he died in October 1964, Hoover sent Truman his last written words: a get-well-soon wish, because Truman was ailing at the time.

And as Truman said in his eulogy to Hoover, “Briefly put, he was my friend and I was his.”

Happy endings are hard to come by in self-governance.

Let’s hope the odds against us today aren’t much greater than Hoover and Truman faced.

Author’s note: Most of the material for this piece is drawn from research at the two presidential libraries over the years and from four publications: TRUMAN by David McCullough, Herbert Hoover the Uncommon Man published by the Hoover Presidential Library Association, An Uncommon Man by Richard Norton Smith, and Herbert Hoover and Harry S. Truman: A Documentary History, edited by Tim Walch and Dwight Miller.

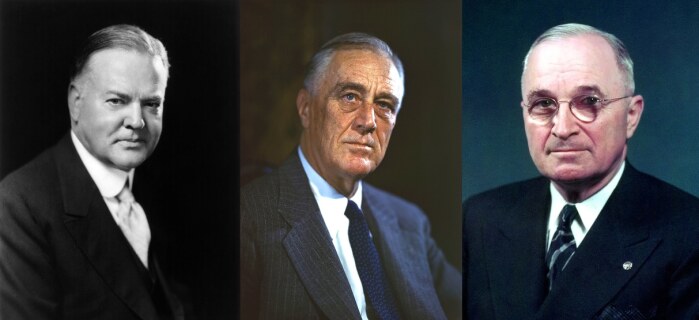

Top images, from left: Herbert Hoover in 1928, photo from the Library of Congress; FDR campaign portrait in 1944, taken by Leon Perskie, CC BY 2.0 license, available via Wikimedia Commons; portrait of Harry Truman in 1947 (cropped), photo from the Harry S Truman Library.

3 Comments

Very interesting

I do think I read this when you first offered it. The review is timely and necessary. FDR was president when I was born, but my first recollection of a prez is Truman. When my dad was in seminary (GI Bill) in KC, he and a friend were walking passed the Truman residence. Harry too was out strolling. He stopped for a chat and a newspaper photographer took a pic of the men with the president. I haven’t read MCullough‘s book, but you remind to do so.

iowagerry Mon 17 Jul 9:37 AM

It feels a little odd to say this...

…but the feeling I have about both Hoover and Truman after reading this essay, and also reading the previous version of this essay, was that both men were grownups. In the best sense of the word.

PrairieFan Tue 18 Jul 12:43 AM

Compromise is Considered Capitulation

This essay is well done. For the greater good, two partisans became friends and worked together. Today, that is considered weakness. Our politics has become bitter and mean. Some politicians, for fear of a primary challenge, are so afraid, they won’t even condemn a former President indicted twice. We have let our politics become sad and devoid of compromise.

BruceLear Tue 18 Jul 9:59 AM