Attribution such as “first reported by” is an appropriate way for journalists to acknowledge another media outlet’s role in breaking news. The Center for Investigative Reporting’s Ethics Guide states,

Any information taken from other published or broadcast sources should receive credit within the body of the story. Reporters and editors also should be aware of previously published/broadcast work on the same subject and give those news organizations credit if they have broken new ground or published exclusive material before any others.

One of Iowa’s leading newspapers doesn’t hold its reporters to the same standard.

Before getting into the conduct that inspired this post, I want to make clear that I highly value the Cedar Rapids Gazette’s Iowa politics and state government coverage, which has informed hundreds of Bleeding Heartland posts. For my money, no paper in this state has a better pair of columnists working now than Todd Dorman and Lynda Waddington. I try to link to content from the Gazette frequently, since many of my central Iowa readers and Twitter followers don’t regularly check the paper’s website.

The issue at hand has been troubling me for some time precisely because the Gazette is a good newspaper, not a rag staffed by hacks.

A few words on definitions: for the purposes of this discussion, a scoop is not one journalist being first to file on a story others were already chasing, or being first to quote a press release or official documents sent simultaneously to multiple media organizations, or being first to report something that quickly would have become public knowledge anyway, like high-level staffers resigning from a campaign, or a candidate ending a presidential bid.

When I say scoop, I mean breaking news that other journalists had not heard about before the report in question appeared, news that might otherwise have remained unknown indefinitely, perhaps forever. Scoops are usually based on an exclusive tip or documents obtained through a FOIA request, though sometimes a scoop can emerge from information that was in the public sphere already–such as a newsworthy lawsuit filed without fanfare, hiding in court records no one noticed for weeks.

A good scoop will drive lots of media coverage. Best practices call for journalists following up to mention where the news was first reported, whether they are mainly recapping what’s already known or advancing the story in some way (consulting additional sources, exploring a new angle). Echoing the standards laid out by the Center for Investigative Reporting, National Public Radio’s ethics guide calls on correspondents to “Attribute, attribute and attribute some more.”

Always be fair to your colleagues in the news media when drawing from their reports. Just as we insist that NPR be given credit for its work, we are generous in giving credit to others for their scoops and enterprise work.

The Gazette is not so generous.

THE CEDAR RAPIDS GAZETTE’S APPROACH TO MATCHING SCOOPS

More than a few times, I’ve noticed the Cedar Rapids Gazette has “matched” a scoop without mentioning that another media outlet had the big news first. Also known as “poaching,” matching is “recycling a published story, often using the same sources. When a journalist breaks a story, other reporters often match the original piece without giving credit.”

The latest instance happened on February 17, when Luke Meredith and Ryan Foley reported exclusively for the Associated Press that the University of Iowa had signed a lucrative contract extension for Athletics Director Gary Barta. Although I don’t normally keep up with sports news, the story got my attention as an example of the university’s lack of transparency under new President Bruce Harreld.

For sports journalists on the Hawkeyes beat, the Barta scoop was of obvious importance. Gazette sportswriter Marc Morehouse posted several tweets, including this nod to Meredith:

“JR” may refer to Jim Burke, the Gazette’s current president and publisher. “Not being an AP paper” means the Gazette no longer subscribes to Associated Press content, a fact Burke confirmed to me last year. CLARIFICATION: “JR” is more likely to be the Gazette’s sports editor, J.R. Ogden.

Later in the day on February 17, Morehouse tweeted out a link to his piece for the Gazette on Harreld backing the University of Iowa’s athletic director. That story covered the same ground as the AP’s report and included Barta’s contract extension and previous contracts, which Morehouse obtained after the AP’s story appeared. The Gazette article cited “UI documents” but did not disclose that the AP broke the news or that university officials had kept the deal under wraps until Foley asked to see the contract.

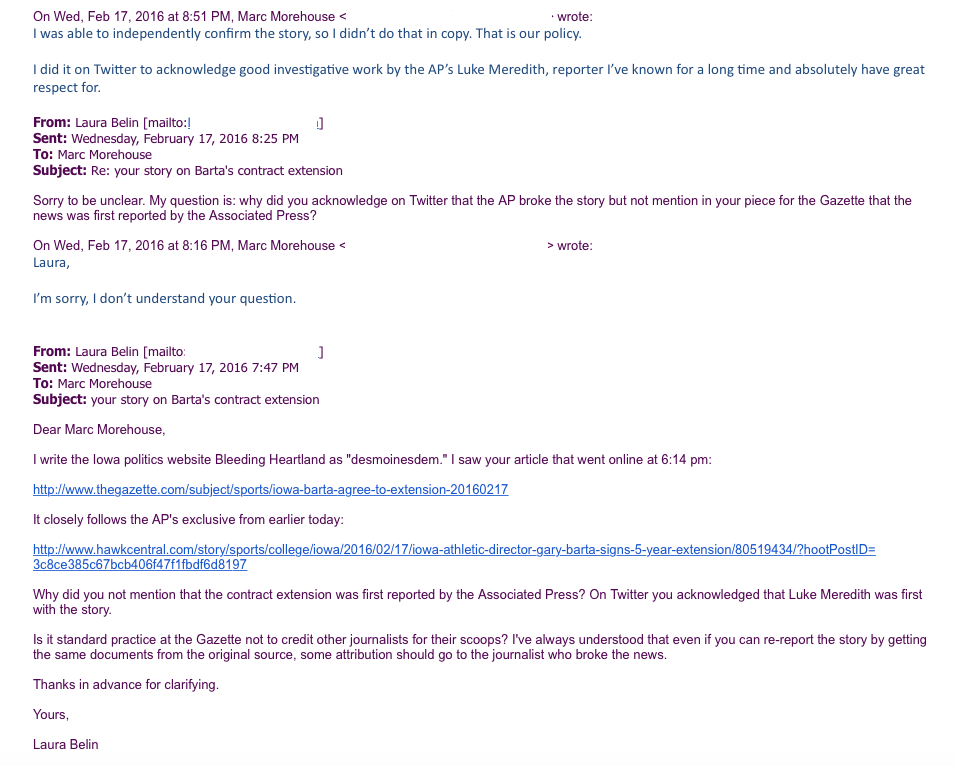

I e-mailed Morehouse to ask why his article didn’t credit the Associated Press, noting that he had praised the AP’s scoop on Twitter.

Since small print is difficult to read on screens, a recap: Morehouse said he didn’t understand my question. I rephrased. He replied,

I was able to independently confirm the story, so I didn’t do that in copy. That is our policy.

I did it on Twitter to acknowledge good investigative work by the AP’s Luke Meredith, [a] reporter I’ve known for a long time and absolutely have great respect for.

Throwing a competitor a bone on Twitter while you replicate his “big score,” giving no credit in your own publication, is a strange way to show “great respect.”

But it was helpful to learn that Morehouse was following his employer’s policy on matching scoops. Our correspondence confirmed my impression that this practice is an institutional problem at the Gazette, rather than a few individuals making questionable decisions.

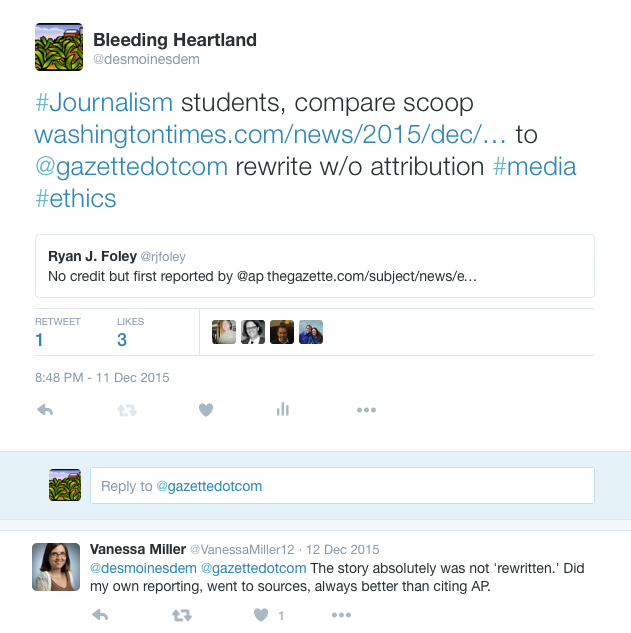

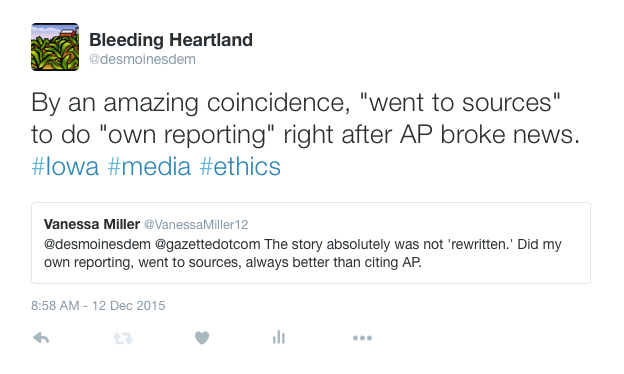

Two months ago, I contacted Gazette management privately to express concerns about a different matching incident. Investigative reporter Vanessa Miller wrote this article about Harreld hiring Eileen Wixted as a communications consultant. The story cited university spokesperson Jeneane Beck and e-mail from Harreld as sources, failing to mention that the AP’s Foley had broken the news about Harreld hiring Wixted earlier in the day. Annoyed by the lack of attribution, I highlighted the problem on Twitter, where Miller and I mixed it up a little.

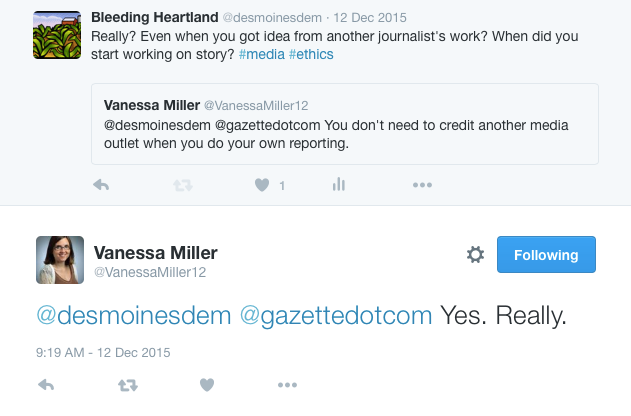

I saw no point in continuing the debate and resolved to let the matter drop. However, before long another person’s comment drew me back in to criticizing the Gazette’s failure to attribute, and I watched in disbelief as someone in journalism studies defended “confirming the story on her own” as a “responsible move.” That exchange led to more online conversation with Miller. She never did clarify when she had started working on the Wixted story, nor did she claim to have been chasing it before the AP’s scoop appeared. She had her own list of grievances, stories the Gazette had first and other media followed without attribution. Several of those pieces were unfamiliar to me but I entirely agree that Miller deserves credit for her exclusives, like everyone else.

In fact, the very next day the Gazette published a superb investigative piece by Miller about former Iowa House Speaker Kraig Paulsen’s new job at Iowa State University. I would be disgusted if a competitor used her work to craft a records request for ISU e-mails, then matched the story (based on her “own reporting”) without reference to Miller’s expose.

That same week in December, the AP’s Foley had another scoop: President Harreld had shocked a staff meeting by remarking that unprepared teachers “should be shot.” A reporter for the Chronicle of Higher Education credited the AP, then advanced the story by reproducing part of the e-mail chain between Harreld and a university librarian. In contrast, Miller’s summary of the controversy for the Gazette a few hours later cited the e-mails but not the AP’s part in bringing the story to light.

Last month, Gazette sportswriter Scott Dochterman took offense at the suggestion that he did anything wrong by reporting on a former football player’s settlement with the University of Iowa. Missing from Dochterman’s narrative: that news too had first been disclosed by the Associated Press hours earlier. A statement from the university was the only source cited in the Gazette’s story.

Until the Iowa Board of Regents hired Harreld last September, Bleeding Heartland rarely covered University of Iowa happenings. The number of matches I have seen in the Gazette during the short time I have been watching university politics closely is disturbing. It makes me wonder how often the paper poaches scoops on beats I don’t follow.

That any reporters or editors condone using another person’s work in this way astounds me.

My training in political writing came from the academic world, not from the study or practice of journalism. Proper attribution is extremely important in academic culture. Was my background skewing my view on the morality of matching? I decided to examine what professional journalists and media commentators say about re-reporting scoops with no credit to the original source.

UNETHICAL, OR MERELY RUDE?

In his appeal to journalists to “Stop matching,” Anthony De Rosa called the practice “an institutional problem deeply rooted within many mainstream newsrooms,” sometimes stemming from a “business strategy” to “Ignore your competition, don’t let your readers know they exist, pretend they didn’t beat you.”

Another unfair aspect of matching relates to the level of effort involved. As Canadian Broadcasting Corporation producer Angela McIvor commented for an article about an alternative newspaper’s major scoop, “It’s frustrating when you put a whole day working your butt off to get a story done and get all the pieces, and then it only takes 10 minutes for another reporter to confirm.”

Sending an e-mail to request information a competitor put on your radar might not even take ten minutes.

Many journalists accept that the person breaking a big story deserves attribution, along with the traffic that comes when other media link to the scoop.

In a 2012 article for Bleacher Report about “Breaking News, Sourcing, Credit & Scoops in Sports,” Dan Levy argued (emphasis added in bold),

Certainly, if [USA Today’s Michael] Hiestand saw the report about [Dana] Jacobson leaving ESPN at Sports by Brooks or The Big Lead before doing his own legwork to confirm the story, he should have credited the original source in his piece. But if he found that information independently with his own reporting, he shouldn’t have to credit an outlet that also had the story just because they hit the publish or tweet button first. […]

Second, it is important to credit the source that alerted you to the information. If the original report was in Wall Street Journal but you saw the story on Yahoo’s Big League Stew, make sure to credit BLS with the tip.

Last, and most important to the topic, if a team supplies a press release for reporters to reference, it’s no longer necessary to credit the original reporter who was first on the story unless the breaking news created the need for said press release. […]

True investigative journalists—those who break stories people don’t necessarily want to get out—are the real heroes in our field. Credit them early and often.

Steve Buttry’s career includes stints at the Des Moines Register and the Cedar Rapids Gazette. He is currently director of student media at Louisiana State University’s Manship School of Mass Communication and maintains a good journalism blog. A scandal at a Connecticut newspaper prompted Buttry to write this 2011 post with advice for journalists on attribution (emphasis added):

Attribution is the difference between research and plagiarism. Attribution gives stories credibility and perspective. It tells readers how we know what we know. It also slows stories down. Effective use of attribution is a matter both of journalism ethics and of strong writing. […]

Attribute any time that attribution strengthens the credibility of a story. Attribute any time you are using someone else’s words. Attribute when you are reporting information gathered by other journalists. […] When you wonder whether you should attribute, you probably should attribute in some fashion.

The apparent rationale for the Gazette’s policy is that once a journalist has independently confirmed facts, s/he is no longer “reporting information gathered by other journalists.” The fallacy is that with the kind of scoops I’m talking about, no one would have checked the story out, but for the original report.

Buttry called on journalists to link more often to other people’s work in this 2012 blog post (emphasis in original):

Honesty is good journalism. If you weren’t first with a story, or a piece of a story, someone will have read the first one. Even if you independently verified every fact in your own piece, linking shows the readers who saw both pieces that you are honest, acknowledging the work that came before and not pretending to be first.

Transparency is good journalism. Some readers want to see your work, and reading that other piece was part of your work, whether it guided your reporting or whether you were racing along the same path and the other reporter beat you to publication. […]

Attribution is good journalism. Often a journalist is actually relying on the work of another journalist. […] Ethical journalism is more than just avoiding plagiarism. In digital journalism, attribution is incomplete without a link.

It didn’t take me long to find examples of furious journalists whose scoops had been poached.

Danny Sullivan “broke a tasty story about a woman suing Google” in 2010. “No one had written about the case before I put my article up. I know. I checked before publishing. There was nothing out there.” Yet the next day, “I discover our story is everywhere, often with no attribution.” Click through for Sullivan’s depressing tale of “How The Mainstream Media Stole Our News Story Without Credit.”

For an entertaining read, try this not-safe-for-work rant by tech blogger M.G. Siegler. He recounted how “every single other publication linked to my story” about Apple acquiring a platform, while the Wall Street Journal ripped off the story without mentioning him. When Siegler complained, a Journal representative explained that their policy is to credit if they “match” a scoop before receiving outside confirmation. However, once a company confirms information first reported elsewhere, “we don’t usually credit.” Just like the Cedar Rapids Gazette.

Siegler’s experience revealed strong differences of opinion in the media world. Mathew Ingram argued persuasively against the Journal’s conduct in his article, “Is linking just polite, or is it a core value of journalism?” Excerpt:

I’ve argued before that I think this failure to link is a crucial mistake that mainstream media outlets make, and also an issue of trust: since the Journal must know that at least some people saw the Siegler post, why not link to it? The only possible reason — apart from simply forgetting to do so — is that the paper would rather try to pretend that it was the first to know this information (and it also apparently has a policy of not linking if a WSJ reporter can independently confirm the news).

Is that the right way to operate online? I would argue that it is not, especially in an environment where trust matters more than so-called “scoops.” I think that is the kind of world we are operating in now, since the half-life of the scoop is so short. But if scoops don’t matter, then why should it matter if the WSJ credits Siegler or not? I think that failure to link decreases the trust readers have, because it suggests (or tries to imply) that the outlet in question came by the information independently when they did not.

To my surprise, a number of reporters defended the Wall Street Journal’s approach. Ingram shared their comments in in this compilation of Twitter posts on the controversy. One of the apologists was Felix Salmon of Reuters. He expanded his thoughts on the Siegler/Journal dustup in this piece for the Columbia Journalism Review:

[I]f you’re matching a story which some other news organization got first, it’s friendly and polite to mention that fact in your piece, while linking to their story. But it’s always your reader who should be top of mind — and the fact is that readers almost never care who got the scoop.

There’s one big exception to that rule, however. Often, a reporter spends a long time getting a big and important scoop, which comes in the form of a long and deeply-reported story. When other news organizations cover that news, they really do have to link to the original story — the place which did it best. Otherwise, they shortchange their readers. […]

As for crediting the news organization which broke some piece of news, that’s more of a journalistic convention than a necessary service to readers. It’s important enough within the journalism world, at least in the US, that it’s probably a good idea to do it when you can. But most of the time it’s pretty inside-baseball stuff. And in the pantheon of journalistic sins, failing to do it is not a particularly big deal.

Salmon’s perspective makes no sense to me. So what if readers don’t care who got the scoop? As Ingram pointed out in response to Salmon and others, “many readers may not care whether we are fair or spell people’s names right, but we do it anyway.”

No one claims it’s admirable to poach someone else’s scoop. That’s as far as the consensus goes, though. Some journalists consider matching without attribution “an ethical issue,” whereas others believe that “if you verify information yourself […] it’s merely courteous to link.”

Since Buttry has put a lot of thought into these matters, I sought comment from him about a hypothetical scenario in which someone gets a scoop related to the University of Iowa. After reading that story, a journalist working for another media outlet goes to university officials to confirm the news, then reports the story without indicating who had the exclusive. Buttry replied by e-mail,

I’d say that this falls more into a matter of courtesy (to readers as well as other journalists) than ethics. To rip something off without attribution and without doing your own work clearly would be plagiarism. I don’t like the practice of playing catch-up without acknowledging the earlier work, but if you’ve done your own reporting, I don’t see it as a matter of ethics. It’s a reflection of a long-standing arrogance that too many news organizations and journalists practice of trying to appear as the authority on a topic, when we know that we are just one of many voices on most topics. I understand the competitiveness that overrides professional courtesy in acknowledging the first journalist or organization to break a story. But I don’t think competitiveness should override good judgment. As noted above, I think it’s discourteous to readers not to link to other sources of news on the same topic. If they’re reading your story, they are interested in this topic. You should link to your sources of information, even if you verified the information they provided. Readers might be interested in reading multiple sources, and you should provide links.

Plagiarism is not the only form of unethical behavior in publishing. In the academic world, “harvesting someone’s footnotes” refers to looking up original sources found by another scholar, then citing them in your own research without crediting the person who brought them to light. If you wouldn’t have known to look up a primary source without seeing it used elsewhere, the researcher who made the discovery deserves some attribution.

Like harvesting footnotes, matching a scoop misleads the reader. An author standing on someone else’s shoulders should not create the appearance of having uncovered information independently.

I followed up with Buttry: “So you still see it as only a matter of courtesy, even if ‘your own reporting’ would never have happened without the rival journalist’s scoop?

How is it ever ok not to let readers know that you followed up on or re-reported news no one would know about if the other person hadn’t published the exclusive?”

Buttry explained further,

I regard a journalist’s primary obligation as being toward the reader/viewer/user etc., rather than toward other journalists. In academia, the readers and peers are the same people in most cases (and actually read citations), so the ethical standards are different. For instance, works of journalism are never footnoted, so the attribution standards in the two fields are significantly different (though links, to me, provide better attribution than footnotes, so if journalists start using links more, I think we’ll achieve higher standards).

I will agree that this is a matter of ethics, but I think there is considerable area between “unethical” practices and the best ethical practices. So I don’t think it’s “OK” to duplicate someone else’s reporting without acknowledgment, but I don’t think it’s unethical if you did the reporting to get the information first-hand. […]

I apply the term “unethical” only to the most egregious behavior: plagiarism, fabrication, failure to verify, failure to correct errors, promiscuous and frivolous use of unnamed sources, serious undisclosed conflicts of interests. […]

I regard this attribution matter as being in that middle area, falling short of the best ethical practice (identifying who broke the story first) and unethical practice (using someone else’s information without attribution or verification).

I hope this helps clarify. I’m with you 100 percent that they should identify and link to your work. I just don’t use the word “unethical” to describe their failure/refusal to do that.

Ivor Shapiro, ethics editor for the Canadian Journalism Project and journalism chair at Ryerson University, believes matching is not morally wrong, but lazy.

“It’s quite frequent that people start thinking in an ethical frame of mind about something (when) it’s really about a degree of excellence.”

My father used to say, “Reasonable minds can differ.” Maybe matching scoops without attribution is not unethical, as I believe and as the ethics codes of NPR and the Center for Investigative Reporting suggest.

Maybe the practice is just lazy and impolite, an arrogant way to conceal that you got beaten to a story but “not a particularly big deal” compared to other journalistic sins.

If so, I wonder why a good newspaper would settle for that standard, when giving credit in these situations requires little effort and few words. Gazette columnist Waddington showed how it’s done in a December takedown of “GOP cronyism”: “A records request to the University of Iowa by the Associated Press found $321,900 in no-bid contracts awarded to [Matt] Strawn’s consulting company.”

See how easy it is?

I asked media critic Jay Rosen whether journalists covering someone else’s scoop should give credit to the reporter who broke the story. He hasn’t published on that topic but commented, “To me those are not specifically journalism questions. They are human decency, ‘being a fair and reasonable person’ questions.”

True that. Also true: what M.G. Siegler said.

FEBRUARY 26 UPDATE: Something is very wrong with the Gazette newsroom’s culture, judging by the reaction to this post. Investigative reporter Erin Jordan asserted that matching other reporters’ work without attribution is “accepted practice,” based on her eighteen years of experience in the field. Jordan considers it nothing more than a “pet peeve” for a reporter to dislike having his work stolen in this way. Two colleagues at the Gazette “liked” her comment (Vanessa Miller and Jessie Hellman).

Jordan is incorrect, as shown by the various ethics guidelines and commentaries I linked to above, showing that many journalists consider it important to give credit when someone else’s scoop happened before the rival journalist did “his own legwork to confirm the story.”

In addition, the AP Stylebook (a reference used by by many media outlets) calls for journalists to give credit to other organizations when “they break a story and AP matches or further develops it.”

Even more astonishing, Jordan told the AP’s Foley, “You should be proud of your many scoops and not take this personally.” What an entitled mindset: don’t take it personally when I lift your work without giving you credit. Challenged on her attitude to copying another journalist’s work, Jordan responded, “It’s not copying if you get the document or interview yourself. But I guess we’ll have to agree to disagree.” Miller liked that comment as well.

What is so hard to understand about the fact that you didn’t do work “yourself” if you sought a document or an interview solely because of another person’s scoop? Another person following the Twitter discussion, who’s not even a working journalist, pointed out the obvious: “If you did not know doc existed or was relevant prior to that on your own, then you owe credit. Jschool day 1.”

Jordan also said matching scoops without attribution has been accepted practice at the Des Moines Register. I am seeking comment from the Register’s Executive Editor Amalie Nash about the newspaper’s attribution policy. Is it like NPR’s, or do they take the Cedar Rapids Gazette/Wall Street Journal approach of letting reporters pretend they didn’t get the story idea from someone else, as long as they “independently confirm”? At this writing, Nash has not responded to my inquiry. I will update as needed. I hope current and former reporters for the Register will contact me confidentially with information on whether matching without credit was tolerated or encouraged there.

I went back and looked at Jordan’s interview with Iowa Watch about an investigative piece she published last August. The story exposed “pros and cons of Student Tuition Organizations,” which benefit from “one of the highest tax credits on Iowa’s books.” Click through to read how proudly Jordan described her work on that investigation. Then imagine how she would feel if someone else used her tips as a shortcut to re-report the conclusions, giving no credit to her or to the Gazette.

Meanwhile, Gazette reporter Brian Morelli chimed in that “reporters are the only one who notice or care who beats who on a story,” and that “most readers couldn’t tell you which publication they read something in, much less who wrote it.” Gazette sports reporter Jeremiah Davis liked both of those comments. I have more respect for the Gazette readers than the newspaper’s staff do, apparently. Look, it’s not complicated. You don’t have to get there first to do good work advancing a story. Nevertheless, the person who broke the news should get credit for putting the story on your radar.

Stealing is not ok, even if readers don’t know and don’t care about it.

By the way, within two hours of publishing this post, I noticed that Morehouse had blocked me on Twitter. Blaming the messenger isn’t the healthiest way to take constructive criticism, but thanks anyway for reading.

SECOND UPDATE: Amalie Nash, the Des Moines Register’s executive editor and vice president for news and engagement, replied by e-mail,

Your article brought up an interesting question. The Register does not have a specific policy on that, but we agreed it’s something worthy of discussion. I agree with the policies your article cited in terms of crediting when the information is exclusive and isn’t simply one outlet getting it a little faster. If we ever use information from another media organization that has it first, we obviously credit the information to that organization. But we haven’t talked a lot about specifically citing “as first reported in XX.” I’m not aware of the situation arising often in my two years here, but there could be circumstances I’m not aware of. As an AP member, if they break or exclusively report a story, we typically publish their story instead of expending the resources to match it.

Bottom line: We’ll be discussing this more in depth at our next managers meeting, and I’m glad to keep you posted.

9 Comments

Speaking as a former journalist

I agree with you that reporters should acknowledge if their first contact with a story came from another media source. For me, the deciding factor was always “how would I feel if I was the one whose scoop was being used without being acknowledged”? It’s laudable that the Gazette reporters did their own reporting once they knew the story existed; that’s far more responsible than just rewriting something without confirming. But I would not have felt comfortable doing so.

Now that we know the reporters are following Gazette policy by doing so, though, the obvious follow-up question is are they actively discouraged from giving credit in print. Clearly Morehouse had no problem acknowledging the work that AP did on the Barta story on Twitter. Did his editors tell him not to include that in print (or did they edit it out)? And has that happened in the past with Vanessa Miller?

I believe the Gazette is privately owned by its employees. I wonder if and how that factors into their policy. I feel it’s a definite factor in the high quality of its news coverage in general.

By the way, it’s a minor point but I believe Morehouse was referring to Gazette sports editor J.R. Ogden when he referenced “JR”.

rosalita Thu 25 Feb 11:13 AM

thanks for that

Certainly, seems more likely he was referring to his editor.

You raise a good follow-up question. Based on my communication with them, I see no indication that Gazette reporters are trying to give credit but are having those phrases removed during the editing process. It appears that they do not consider it necessary to cite someone else’s work once they have confirmed the facts.

desmoinesdem Thu 25 Feb 12:33 PM

Never a journalist, but...

I agree with you 100%. And as a reader, I do care about attribution. I pay attention to details like that. ( I also kept reading and thinking, what would Jay Rosen say? And then you had the quote. Thank you!)

As I was reading, I wondered if there’s a place for ethics certification in the media, a little symbol that could be placed on a website to let readers know whether or not that publication adheres to certain standards. Maybe many people wouldn’t care. But some journalism school that teaches the difference might sponsor it, and raise the profile of the issue among jounalists and digital media (and maybe even among readers) to make it a valued thing. It certainly seems like it should be taught as part of ethics (which should be mandatory for journalists — as just about for all professions, in my opinion). Just an idealistic thought….

x Thu 25 Feb 12:54 PM

Slow. Hand. Clap.

Now I know why I like this blog so much. Unlike you (academically trained), I was trained as a journalist (general assignment/investigative) in the DM Register newsroom of 1966 until the Michael Gartner era. Anyone who would’ve come to Housh, Kluender, Paul, Eyerly, or Kong without proper attribution would’ve left holding their a## in their hands.

That you’d even have to mention such issues, signals our descent into the click-bait wars where they don’t care if you read it as long as you click-it. (speaking from the media owner, not the reporter perspective.)

Are our journalism schools down with this? Drake J-School during my days there certainly had clear attribution rules.

(Well, that was pre-Internet old timer!!)

Right. In the digital realm, people believe that the rules of the “natural world” are suspended.

Look at the music world since napster. Most people would never walk into a record store and steal my CDs of the shelf, but online, all it takes is two clicks and its yours–possibly without having to pay anything.

The human capital of time spent developing your craft, practicing and producing it and then presenting it for consideration/payment seems to have been negated in the digital age.

The new age of digital property owners consider our work, whether journalist or jazz musician, to be just data to be procured at the lowest possible price point.

Again, I haven’t been in a collegiate level j-school program for a long time. Curious how these topics are covered.

Thanks again. J-school spirits of the past are smiling on you.

dbmarin Thu 25 Feb 6:08 PM

I am hoping to hear from some journalism teachers

I want to know what they are teaching students in j-schools about attribution these days.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Lynda Waddington blogged for years before joining the Gazette. I have read that bloggers are more generous than traditional journalists are about linking to other news sources.

desmoinesdem Thu 25 Feb 9:59 PM

True that!

Bloggers started out as special interest community gathering points in cyberspace. The whole idea was to crowd-source information, on issues of relevance to that community. Newspapers are closed, competitive, and increasingly time/resource strapped operations that are proprietary down to their DNA.

dbmarin Fri 26 Feb 8:09 PM

Sorry

Didn’t mean to single-space.

dbmarin Thu 25 Feb 6:10 PM

One more Thought

Seeking Readership as a goal has given way to merely seeking (click-worthy) attention. Attention, no matter how brief, means you get paid on the internet. The internet doesn’t care if you stay to read the entire article.

When your goal is to grab attention rather than cultivate true readership, crediting originators, no never mind giving <> some “attention” is literally bad business.

dbmarin Thu 25 Feb 7:53 PM

I think time pressure is a factor too

Newsrooms have been cut back so much, reporters are over-extended. It’s easier to match someone else’s story than to put in the effort to break new ground.

desmoinesdem Thu 25 Feb 10:07 PM