This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

September 1974. One building or the other might have been doomed.

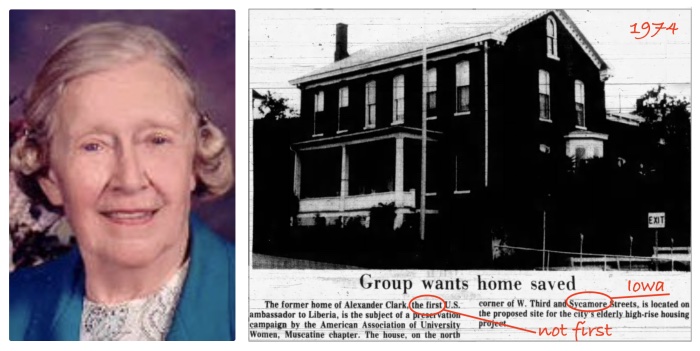

The fate of the historic Alexander Clark House was at stake. So was the long-planned and much needed apartment high-rise that now bears the name of the Muscatine resident one historian calls “the most important African American leader who almost no one has heard of.”

An official of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) wrote to James Tracy, chair of the city’s Low Rent Housing Commission: “Thank you for your telephone call advising us that a group in the Muscatine area has advanced a proposal to preserve one of the older homes on the…property as an historical site. It is indeed unfortunate that this movement was started at such a late date in the life of your project….”

Delay could jeopardize already troubled federal funding, HUD warned.

Tracy promptly wrote on behalf of his commission to the director of the National Advisory Council for Historic Preservation: “Preservation of the Alexander Clark residence will eliminate critically needed low cost quality housing for Muscatine’s inflation-riddled elderly. We seek not to forget or desecrate the memory and importance of [Clark]. We only seek to provide housing and fitting memorialization….”

About the same time, the national preservation official received research findings compiled by a few Muscatine women. Adrian Anderson, State Historic Preservation Officer, wrote:

Alexander Clark, according to the attached historical summary, may well be the most important contributer [sic] to the black sufferage movement in Iowa since the Civil War. The proposed project would, by destroying a building owned and presumed to be the residence of Mr. Clark, remove from public benefit a point of inspiration and cultural identification.

“[T]he community has not accorded Mr. Clark the recognition due him, even in the course of our investigations here,” Anderson wrote. “Notification of the existence of a building associated with Mr. Clark was not sent…until 11 September, 1974, prior to a public meeting to discuss the project. No one bothered, during that meeting, to mention the information had been sent to the State.”

In October a HUD official in Des Moines wrote to U.S. Secretary of the Interior: “Properties which appear to be eliglible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places have been identified in the proposed site of a project to provide Low Rent Public Housing for the Elderly in Muscatine, Iowa.” He requested a determination “as expeditiously as possible.”

That month Mayor Ronald Hansen also wrote to the Secretary of the Interior: “This letter accompanies a great deal of information attempting to reconcile the apparent conflict between the [Clark residence] and the proposed elderly high-rise.… The need for such housing has been extensively documented…during the past five years.”

“The [city] was first made aware of the historical significance two (2) days after the September 7 Notice to Bidders. This information came as a complete surprise…since this location had been designated for the elderly high-rise project for over a year and well known throughout the community.”

The mayor said Clark’s achievements “must be recognized [but] directed toward the man and not the building. In weighing this factor against our critical need for improved housing facilities for the elderly, it is the continued position of the [city] to proceed with this project with appropriate memorialization of this site as quickly as possible.”

Anderson’s letter had concluded with this stark judgment: “The lack of any expression of support for the preservation of the building by members of the black community is also a factor to consider, since the white community does not appear interested enough to provide promise of financial support.”

But the Clark story had been found just in time. The campaign to save the home had just begun.

In November the U.S. Park Service determined the property eligible for listing in the National Register—a process completed for the house in October 1976 after relocation a half block away.

The woman who did the bulk of the research for both the 1974 intervention and the formal nomination was Elizabeth “Bette” Veerhusen. She searched newspapers and records at Musser Public Library, copying by hand and typing at home.

Duffy DeFrance, children’s department head, assisted her. “I was a history major…. Bette loved history and preservation. She was very upset that the Samuel Clemens house had been demolished.”

“Bette took lots of notes. She wrote in tiny handwriting.”

DeFrance’s memory is part of a photo exhibit opening February 16 at the Muscatine Art Center. “Faces of Hope” features portraits of the first residents of the Clark House high-rise. Photographer Bob Campagna served as the housing agency director during planning and construction. The photo directory he made “as a way of creating community” was to launch the career he has pursued ever since.

Campagna will tell his side of the story on March 23 at the Art Center.

Next time: Women who saved Clark’s house

Top image: Elizabeth “Bette” Veerhusen (1923-2004) Her obituary said: “She received the Excellence in Preservation Award for the Alexander Clark House by the City of Muscatine in 2003.” Photo with caption, Muscatine Journal, September 18, 1974.