This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal in December.

Reconstruction after the U.S. Civil War. That’s where I’m headed in this series, what I’m pondering as I write this year-end column.

I was raised on the Watch Night tradition started by Moravians and adopted by Wesleyans in England and brought to America. Black Americans gave new meaning to Watch Night on December 31, 1862, praying and watching for President Lincoln to make good on his call for freeing slaves in the rebellious South. It came to be Freedom’s Eve.

Muscatine Journal, December 30, 1865:

The colored people of this place will celebrate Emancipation Day (next Monday) by a parade with music during the day and by speeches and other exercises at Hare’s Hall in the evening. Monday will be the second anniversary of President Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation. The blacks have abundant reason to hold the day in grateful remembrance, as the dawn of the time when the bondage of their fellow-countrymen was ended.

Muscatine Journal, January 3, 1866: “During the day a procession passed along the principal streets and in the evening appropriate exercises took place in Hare’s Hall, which was decorated with flags, portraits of President Lincoln and evergreens. The hall was crowded with people, about two thirds being white.”

The reporter praised Alexander Clark’s reading of Lincoln’s proclamation.

Would I know about the remarkable leadership of Alexander Clark had our family never come to Muscatine? Or the difference between the Methodist Episcopal denomination of my youth and the African Methodist Episcopal Church, in which Clark became an international figure? Or the emancipation celebrations that united residents here, at least for a time? I wonder.

Because I was raised on Civil War lore, I did know Iowa sent more soldiers per capita to free the slaves than any other state. My Grandmother Clark was devoted to caring for the veterans; her father had been one.

It was Christmastime at Marion Street Methodist, four blocks from our home in West Boone. A good storyteller, my father was in charge of the children’s sermon that morning, and I was happy to be his accomplice.

He started off reciting words from a popular carol: “I heard the bells on Christmas Day / Their old, familiar carols play.”

We all knew the words, even the kids, because it was a hit of the season on the radio, recorded by Bing Crosby and others.

Dad continued the recitation, smiling sweetly. But then, solemnly, he intoned a new stanza instead of the words we knew. That was my cue. Pulling on gloves, I reached behind the piano and lifted out the square of sheet metal we had hidden.

“Then from each black, accursed mouth / The cannon thundered in the South, / And with the sound / The carols drowned / Of peace on earth, good-will to men!”

On “cannon thundered” I grasped and shook with all my might. A rumble-roar filled the sanctuary, surprising us all. Everyone agreed afterward that the effect really worked.

And then another strange verse.

“It was as if an earthquake rent / The hearth-stones of a continent, / And made forlorn / The households born / Of peace on earth, good-will to men!”

The pretty carol was actually part of a sad poem about the ugliness of war, Dad said, about our country’s tragic Civil War. Ugly reality is often hidden underneath pretty wrappings, he said.

You probably recall the upbeat ending.

“God is not dead, nor doth He sleep; / The Wrong shall fail, / The Right prevail, / With peace on earth, good-will to men.”

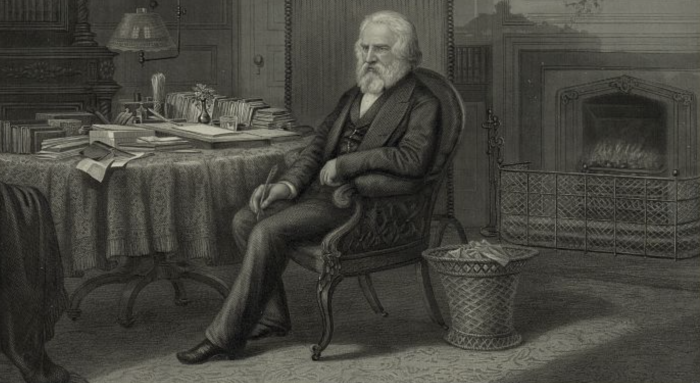

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote that poem in 1863, I learned, and I thought of his sadness often during the Civil War centennial years that followed. And every year at Christmas.

Wrong shall fail and Right prevail? Do the good guys really win in the end?

When wars end—and they do—what then? Get over it? Just move on?

Or enforce “peace” until the losers and their grandchildren forget the bitterness of their loss or else acknowledge they were wrong? Or else submit for now but rise again later to fight again some other day?

As if an earthquake had shattered us. Reconstruction plus assuring rights for four million new citizens was the nation’s challenge at the Civil War’s end.

Muscatine Journal, January 13, 1866: “We believe that the Governor [William Stone] expresses the sentiments of a large majority of the people of this State on the re-construction policy. It will be seen that he is strongly in favor of negro suffrage, and recommends … an amendment to the Constitution of this State striking the word ‘white’ from the article on suffrage.”

“Let us have peace” became a victorious general’s campaign slogan. As President, Ulysses S. Grant made Christmas an official federal holiday in 1870, an attempt to unite North and South. (Grant was a Methodist, by the way.)

Reconstruction after conflict. No easy answers, then or now. Starting wars is so much easier than ending them.

Next time: Boldly for equal rights

Top image: Longfellow in his study, engraving by Samuel Hollyer (Library of Congress).