Dan Guild is a lawyer and project manager who lives in New Hampshire. In addition to writing for Bleeding Heartland, he has written for CNN and Sabato’s Crystal Ball, most recently here. He also contributed to the Washington Post’s 2020 primary simulations. Follow him on Twitter @dcg1114.

Polling is fundamentally broken, and political forecasting is broken as a result. As a result reporting on politics is broken and focuses on minor differences in polling, rather than discussing what the candidates believe and want to accomplish in office.

Some of the biggest misses in 2016 and 2020 came from what were once thought to be gold-standard pollsters. The most accurate pollsters turned out to be firms with right-wing associations like Trafalgar. The 2020 polling misses were not uniform—they were not as large in Nevada or Georgia—and no one is really sure why. There are various theories.

Let’s start with the data.

THE RECENT HISTORY OF POLLING ERRORS

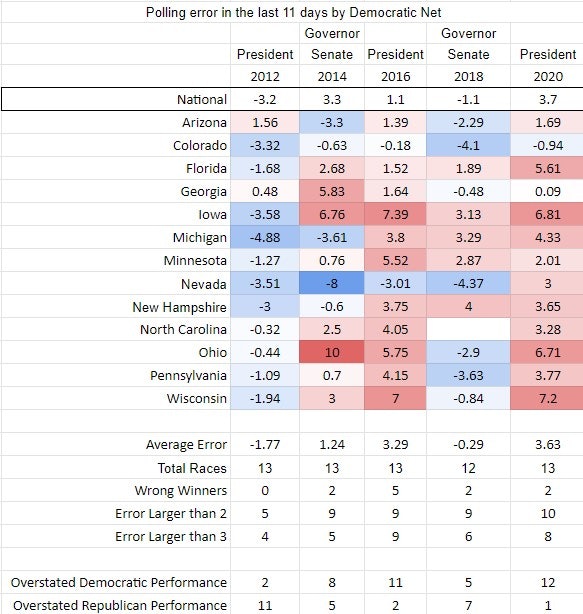

This chart calculates the average error of polls released within the last eleven days before the election. For example, Arizona polling overstated Democratic performance by 1.39 percent in 2016. Alternatively, polls in Colorado understated Democratic performance in 2012 by 3.32 percent.

A few takeaways from this chart:

A 3-point lead is not very big.

In the last three election cycles, more than half of the late polling in battleground states was off by more than 3 points. Why does this matter? When I break out the current data for U.S. Senate races below, you will find a large number of close races.

As a result, the history of the last ten years suggests control of the Senate is a tossup right now.

In three of the last four elections cycles, errors have not been uniform.

In 2016 and 2020, almost all of the error was in one direction. Conversely, most of the error in 2012 was in the opposite direction. We should expect polling to miss in one direction.

Polling has missed most consistently in the Midwest and Rust Belt.

Many of those states (Iowa/Michigan/Ohio/Pennsylvania/Wisconsin) now have closely fought Senate contests.

NO CONSENSUS ON THE MOST RELIABLE POLLSTERS

Because some conservative pollsters performed well in 2016 and 2020, they have found PAC/media money to fund themselves. They account for as much as half of the polling in key battleground states, and those pollsters are having an enormous effect on how these races are viewed.

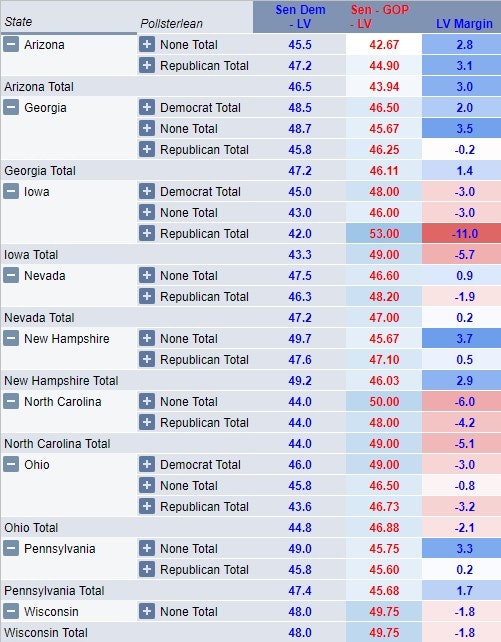

The next chart shows polls released within the past eighteen days, broken out by the partisan lean of the pollster.

In some states, there is little difference between Republican pollsters and those from the mainstream media (see in particular Arizona). In North Carolina, Republican polls are actually more favorable to Democrats than neutral pollsters.

But in the key battleground states of Georgia, Nevada, New Hampshire, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, the differences are significant. Ohio, for example, is a surprise tossup state according to the neutral pollsters.

That Iowa is close is a shock – and Republican pollsters may be making the race between Senator Chuck Grassley and Democratic challenger Mike Franken look less close than it actually is.

Here is the problem, though. Ignoring conservative pollsters (such as Trafalgar Group, Insider Advantage, Rasmussen, Cygnal, and Wick) has made averages less accurate in recent cycles. Wick was one of the most accurate pollsters in 2020. They surely have had their own misses (Trafalgar’s last 2018 poll in Georgia missed by more than 10 percent, and their last 2018 poll in Ohio missed by more than 7 percent).

Before 2016, we had a sense of which pollsters to listen to and which to ignore. That is no longer the case. The relatively few pollsters who did well in 2016 and 2020 were not as accurate in 2018.

THE BIG STORY NOT BEING COVERED

In my opinion, the big story of 2022 is that Democrats are competitive despite relatively high inflation and an unpopular president. History teaches us that the Democrats should be getting killed. Right now, the data does not support that conclusion.

In fact, if you look at polling from neutral pollsters, the Democrats are well-positioned to win Senate seats in states that were the key battlegrounds in 2016 and 2020. That is very surprising.

Recent history predicts that the party with an unpopular incumbent president should expect significant losses in Congress. It happened in 1994, 2006, 2010, 2014, and 2018. And it may yet happen this year.

But by and large, election coverage is not discussing this dynamic. Instead, you get stories like this Washington Post article about vulnerable House Democrats. The piece cites two polls, both reputable, to support the tried-and-true narrative of Democrats in disarray. However, my own average of nationwide polling shows the generic ballot is essentially tied.

Why are reporters missing this dimension? The first table I posted above hints at the likely reason. Reporters are scared to write a story about Democratic candidates doing better than they should be doing, because they were burned in 2016 and 2020.

And that is how polling broke political reporting.

This disconnect could fuel threats to our democracy. Polling misses give rise to conspiracy theories. If I were a conservative, I wouldn’t believe the polls after 2020 and 2016. If the polls underestimate Democratic performance in 2022, many Republicans will scream that the election was stolen.

But the crisis goes deeper than that. Polling drives media reporting of campaign events. For instance, coverage of the presidential debates in 2020 often concluded that the debate was a tie, and therefore a win for Joe Biden, since he was well ahead. But that analysis drew from polling that turned out to be wrong. The election was actually far closer than we realized during the 2020 debates.

How should reporters be covering the polls? They should emphasize how close this election is, and that we don’t know and have no way of knowing who is going to win, given how close the recent polling has been. That is what these surveys can tell us.

My hope would be for campaign reporters to stop trying to predict the future and instead focus on the salient issues, so voters can make informed decisions.

Top photo: U.S. Senate candidate Mike Franken speaks to an audience in Sioux County on October 21. Cropped from an image posted on the candidate’s Facebook page.