This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

“Look! They included Susan, and with a photo we haven’t seen!” my wife exclaimed while perusing a Sunday newspaper article about “17 Iowa women who changed the world.”

“Starting with this school year, the combined middle schools of Muscatine have a new name marking an old decision that changed lives for many, including a 12-year-old girl who didn’t want to stop learning: Susan Clark Junior High School.” (Des Moines Register, March 29, 2020)

The Register was celebrating “the progress women have made in the 100 years since getting the vote.” The photo illustration, as it appeared to be, was credited to West Des Moines Historical Society.

When I contacted her, the writer replied: “It is not a photo of Susan, but a rendering of what she would have/could have looked like.… I have updated the caption to reflect that. Sorry to get your hopes up!”

I contacted the creator. He called it “merely a ‘period’ picture.” The online caption now says “rendering.”

Jean and I had been active in the school naming effort. For years we and others had been on a quest for an authentic picture of Susan at any age, at any period. We will never know what she looked like until someone discovers a photograph which likely exists somewhere.

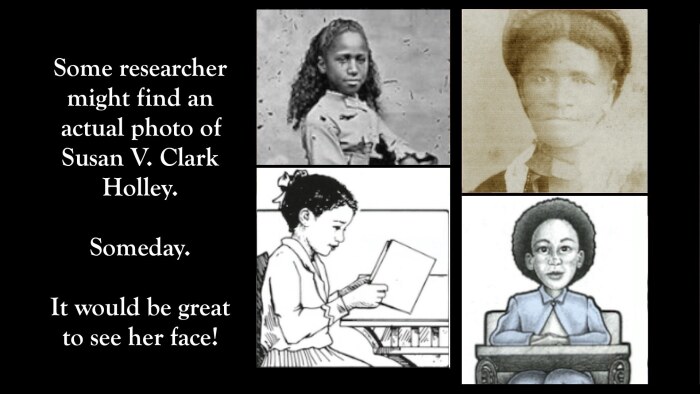

Meanwhile, several artists have presented “renderings” from their imaginations. First, the Duffy DeFrance mural at the Clark House apartments (1979). Then a line drawing in Outstanding Iowa Women: Past and Present by Ethel Hanft and Paula Manley (1980), and drawings by Mary Moye-Rowley in The Goldfinch, a publication of the State Historical Society of Iowa (1996).

Right now we are working with another artist on a children’s book project. (More about that later!)

From a column by Gil Dietz, editor of the Muscatine Journal (July 5, 1975):

Does anyone have a copy of a photograph of the Muscatine High school senior class of 1871? Susan Clark, daughter of Alexander Clark, was a member of that graduating class. Susan was the first black person to graduate from high school in Muscatine, and perhaps the first in the state of lowa. In 1867, when the Muscatine high school had refused to enroll his daughter, Alexander Clark sued for her admission to the Iowa Supreme Court and their ruling in that case established the law prohibiting discrimination in lowa public schools.

Dietz tells that Bette Veerhusen “who has done extensive research on the Alexander Clark family, has been unable to locate any photographs of Susan.”

Dietz then says: “A Muscatine Journal story in 1871 indicates that a commercial photographer took a picture of the class, but that was long before photographs were published in the newspaper.”

“The high school does not have a copy of the photograph, and neither does the public library. Somebody in Muscatine might have one of the pictures in a family album. If a photograph of that class is ever found, Mrs. Veerhusen would very much like to see it.”

I cannot find such an 1871 news item, nor any more clues to that photo or any other.

Clues for searchers: As an adult, she was known by her married name, Mrs. Richard Holley (or Holly). By the time of her death in 1925, she had been known as Mrs. S.V. Holley most of her life. Before that, even as a young adult, she was called Susie.

Can it be that there really is no photograph? Susan was a 20th century woman, prominent in church and community affairs throughout her life, statewide in Iowa and later in Chicago. We still consider it possible she might yet be identified conclusively, perhaps in a group photo.

Well, there is that one photo, the one Drake University Law School used for advertising its 2018 week of “Clark 150” events commemorating the 1868 Iowa Supreme Court ruling in Clark v. Board of Directors. It shows a Black woman in a bonnet—maybe Susan?—along with an authentic portrait of her father.

That image had proliferated after being used in the 2012 Iowa PBS documentary “Lost in History: Alexander Clark.” The registrar at Muscatine Art Center, which holds the print, had warned the filmmakers not to represent it as Susan. She called it the portrait of an unidentified African American woman taken by a Muscatine studio. The period wasn’t clear but appeared an unlikely fit for Susan.

But when the show came out, she filled the screen—whoever she was. Solemn-voiced narrator Simon Estes intoned the words (probably of writer/producer Marc Rosenwasser): “This is thought to be the only photograph of the teenager at the center of the historic case.”

From a slide on the video loop that plays in the entrance hall at Susan Clark Junior High: “Some researcher might find an actual photo of Susan V. Clark Holley. Someday. It would be great to see her face!”

Next time: Whites and Blacks together?

Top image: The photo portrait that does not show Susan V. Clark, plus some artists’ images imagining how she might have looked.