Early this month, Lee Tesdell invited me to the Prairie Strips Field Day he hosted at his family’s century farm in northern Polk County. I’ve visited many prairie restorations in progress, but this was my first encounter with a prairie strip in the middle of rowcrops.

Lee has long employed conservation practices on his farm and is five years into his prairie strip project. Every year, he finds new native plants in the corridor.

Before the program started, I snapped a few photos of the common milkweed plants clustered around the farm entrance. They were starting to bloom.

A llama was checking me out. Lee raises lamb for the Iowa Food Cooperative, and explained that he bought Lennie a couple of years ago to be a guard llama for his sheep. (Apparently llamas will chase off coyotes or aggressive dogs.)

Tim Youngquist of Iowa State University, who helped Lee seed his land, was on hand to talk about the prairie strips program. He’s on the left here. On the right is Jordan Giese, a graduate student who is researching the impact of prairie strips on bird populations. Jordan attached location devices to several pheasant on Lee’s property and found that one of them sheltered in the prairie strip vegetation for much of the winter.

Tim and other ISU researchers have found “that by converting 10% of a crop-field to diverse, native perennial vegetation, farmers and landowners can reduce sediment movement off their field by 95 percent and total phosphorous and nitrogen lost through runoff by 90 and 85 percent, respectively.” This conservation practice is not just for organic farms; “integrating small amounts of prairie into strategic locations within corn and soybean fields — in the form of in-field contour buffer strips and edge-of-field filter strips — can yield disproportionate benefits for soil, water, and biodiversity.”

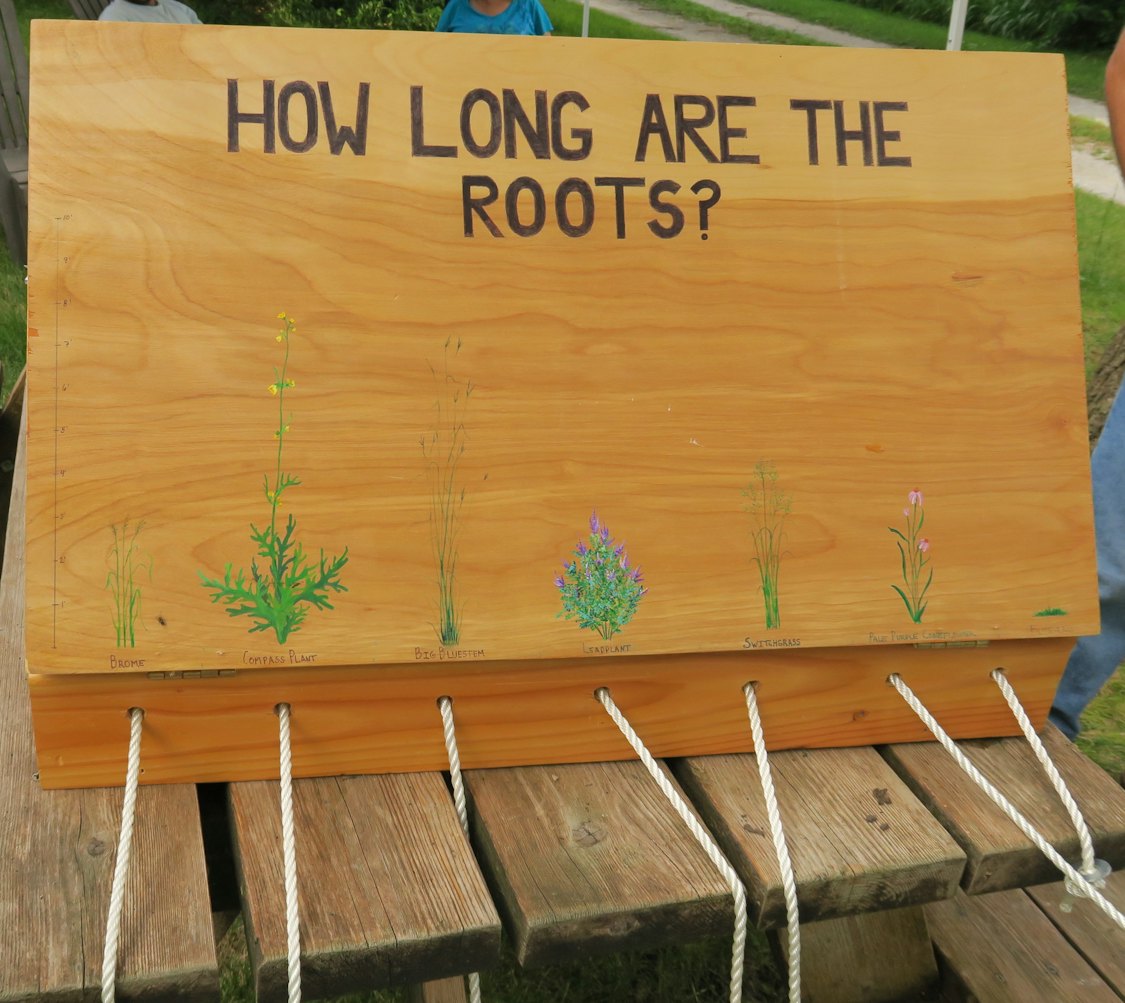

Tim brings this teaching tool to his prairie strip talks. Volunteers pull on the ropes to illustrate how shallow the roots are for Kentucky bluegrass or brome, compared to native prairie plants. For instance, compass plant and leadplant roots go more than ten feet underground, anchoring the soil and capturing more rainfall.

ISU’s Prairie Strips website explains,

Grasses such as smooth brome, tall fescue, orchard grass, and Kentucky bluegrass are widely used to provide ground cover in agricultural areas of the U.S. Corn Belt, but they are relatively weak-stemmed and prone to laying flat under heavy rain. They are useful for grassed waterways that are intended to convey water while preventing erosion. In contrast, native tall-grass prairie communities are typically dominated by stiff-stemmed grasses and erect forbs (i.e., wildflowers) species that are less prone to collapse under heavy rain and more effective in providing resistance to water flow and sediment movement. […]

While plantings of perennial monocultures are beneficial in keeping roots in the ground for the entire year, they will not have as diverse and abundant root systems as diverse plantings. Thus more time will be required to provide soil health benefits such as breaking up compaction, improving infiltration, and raising soil organic matter. For this reason, they are also less resilient to weather extremes.

Lee shared a little of his family farm’s history and held up examples of tile used to drain fields in the early 20th century (the ceramic example) and today (plastic). Tiling contributes to dirty waterways in Iowa and downstream by moving rainwater and pollutants like nitrates quickly off the land.

Lee seeded his prairie strip on land that had formerly been a terrace designed to reduce runoff. He used a mix containing about 60 different prairie species, purchased from the Allendan Seed Company in Winterset. He has identified about 30 of those, finding new wildflowers every year.

The most diverse sections of his prairie strip are at the north and south ends. In the middle, the brome grass planted decades ago remains stubbornly dominant, as you can see in this picture. During our group outing, Tim and Lee discussed a possible spring burn to help knock back the brome next year.

Lee rotates crops, and this year, the field running alongside the prairie strip (on the right side of this photo) is in soybeans. The large group of yellow and orange flowers near the north end of the prairie strip are ox-eye, and beyond the strip, corn was already well above waist height.

Some of the soybean plants had small pink flowers open.

The farmer who planted Lee’s beans this year accidentally planted some in the prairie strip. Some soybeans are growing in this photo alongside the bright yellow black-eyed Susans.

This colorful plant is unfortunately an invasive vetch, probably hairy vetch (cow vetch is a related species). There was a lot of vetch near the north end of Lee’s prairie strip.

Turning to the native plants, quite a bit of hoary vervain is blooming in this area.

This one was new to me. I think it’s an unusual pink variation of hoary vervain, though someone in the Iowa wildflower enthusiasts Facebook group suggested that it could be narrowleaf vervain instead.

Speaking of pink, lots of wild bergamot, also known as bee balm or horsemint, was blooming or on the verge of blooming.

These deeper pink flowers are purple prairie clover.

Sad to say, I was so excited to photograph other plants that I missed the patch of Virginia mountain mint Tim and Lee pointed out to some others in our group. But I did capture some wild quinine, which is one of Lee’s favorites.

Staying with the white color scheme, here are some prairie sage plants.

Rattlesnake master was blooming in several parts of the prairie strip. The brown remnants of last year’s rattlesnake master are visible to the lower right in this image.

I couldn’t recall seeing Illinois bundleflower before, so was excited when Lee pointed out some patches of this native plant.

A closer look at Illinois bundleflower leaves:

More Illinois bundleflower blooming:

I’ve only seen windflower, also known as thimbleweed, a few times elsewhere. These plants are thriving on Lee’s property.

Some windflowers are blooming, while others have seedheads forming in that characteristic thimble shape:

A closer look at one flower:

A lot of giant ragweed was growing the south end of the prairie strip. Lee’s son was helping to pull up this native (but undesirable) plant before it blooms.

We missed the peak of the pale purple coneflowers.

I was wary of this plant, thinking it might be the dreaded wild parsnip. But it was in fact the native golden Alexanders, which bloomed a few weeks earlier.

Other plants had yet to bloom. Here’s Lee’s photograph of whorled milkweed, which he’s seeing this year for the first time on his property. He called it “a new milkweed that doesn’t look like milkweed!”

This stiff goldenrod will be blooming in August. I forgot to photograph some ironweed plants, which also hadn’t begun flowering.

This common evening primrose plant on the left may not produce any flowers this year, as it’s been ravaged by beetles. The black-eyed Susans were doing fine, though.

More cheery yellows: ox-eye (lower right) in full bloom, near black-eyed Susans.

The gray-headed coneflowers were out in force.

Mostly gray-headed coneflowers in the foreground; mostly ox-eye in the background.

Heading back to the north end of the prairie strip, Tim showed us a bird’s nest embedded in the plants, a little ways off the ground. It didn’t seem to be in current use; he speculated that red-winged blackbirds may have built this nest.

UPDATE: On July 24, Lee tweeted this photo of a compass plant blooming in the prairie strip.

1 Comment

Lovely photos, nice prairie strip!

I’m not sure wild quinine is native to Polk County, but it’s definitely native to part of Iowa, and the same is true of Illinois bundleflower. It’s fun to see this much floral diversity in a farm planting.

Frankly and unfortunately, what also impresses me is the lack of herbicide drift damage in these photos. There was a lot of drift damage in the last prairie strips I visited, and I’m hearing about drift damage this year to prairie flowers in various locations.

I hear anecdotes about farm herbicide drift damage each year, and often see damage myself. The stories and sightings this year have included damaged veggies, gardens, wildflowers, trees, shrubs, and vines. And I also hear about spraying that happens when the winds are too high. And there’s also the issue of oak tatters.

Iowa needs reporting on herbicide drift. The topics could include everything from whether IDALS or the DNR has any real idea how much non-crop drift damage there is every year, to the reasons why so many rural Iowans (understandably) don’t report drift damage to the official system. It could be an interesting story. But in 2022 Iowa, there are so many stories. Journalists have so much to cover, and too little time and funding.

PrairieFan Wed 27 Jul 1:20 AM