This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

Juneteenth is an easy holiday to miss if you aren’t watching for it. Still, we Iowans pride ourselves on being out in front on justice and equality, so this is for us.

You probably know it’s about the Emancipation Proclamation and the outpouring of jubilation when the long-delayed news finally reached Texas.

Did you know Governor Tom Vilsack signed a bill in 2002 declaring the third Saturday in June as Juneteenth National Freedom Day in Iowa? Then last year, amid a season of “racial reckoning,” President Joe Biden signed the bill designating Juneteenth a federal holiday.

The historic pages of the Muscatine Journal yield few mentions of the word. The first I find is a 1985 column by Aldeen Davis, titled “Texas has its own holiday.”

In 2004, Mayor Dick O’Brien declared June 19 as Juneteenth in Muscatine, and the Journal announced “Muscatine’s first Juneteenth Celebration.” In 2006 Alfred and Retha Monroe were honored as Juneteenth king and queen. In 2019, Muscatine Art Center hosted a Juneteenth event featuring presentations by pastors Jacque McCoy and Annabel Williams-Blegen.

That’s all I could find for Juneteenth, in searching back to 1840. However, looking up “emancipation” uncovers a different story. At least as far back as 1856, African American residents celebrated freedom anniversaries.

The colored citizens of Muscatine will hold a Celebration, to-morrow (1st of August,) in commemoration of the Emancipation of the West Indies. The citizens of Muscatine who feel desirous of witnessing the celebration are invited as spectators. The ceremonies will take place in the grove near J.J. Hoopes’. A dinner and several speeches will be given on the occasion.

August 3, 1857. The Journal reported a procession “in commemoration of abolishment of slavery in Jamaica” starting at Bethel A.M.E. church and ending at “Hoops’ Grove” with food and music and an oration by Pastor Cain and address by Alexander Clark.

Intriguingly, that article says the participants were “the colored citizens of Muscatine, with a number from other parts of the State”—citizens—at the very moment when Negro suffrage was on a state referendum ballot, along with ratification of an amended constitution. (Iowa’s voters would adopt the constitution and reject racial equality, both by large majorities.)

The August holiday marked Britain’s passage of the Slavery Abolition Act on August 1, 1834, proclaiming liberty for 800,000 people enslaved in its colonies.

So, before they were recognized as citizens—or even as persons with human rights “which the white man was bound to respect”—Muscatine’s Black community was holding freedom marches.

I find local celebrations throughout the rest of the 19th century. Sometimes they recalled President Abraham Lincoln’s “preliminary” proclamation, September 22, 1862, giving three months’ warning to the rebel slave states. Mostly they were held on or near January 1, the day in 1863 when the limited emancipation took effect.

Often the events were carried out by “our colored people,” but again and again I see reports of participation by a wider community. Sometimes it’s said “many” white people attended. Almost always with meals, often fundraisers, sometimes processions with brass bands, usually music and drama.

And always readings of the Emancipation Proclamation and Declaration of Independence. The 1877 proclamation reader was “Miss Susie Clark,” daughter of Alexander Clark. In 1890 and 1892, his granddaughter Clara Appleton read the proclamation.

Not surprisingly, Clark himself often took a main role. His absence might be noted if he was not present in Muscatine; speaking elsewhere, the orator always in demand.

Sometimes white speakers and performers are mentioned. Clark’s friend Henry O’Connor was a favorite; Pastor A.B. Robbins another.

January 1880: “The speaking was short—A. Clark occupying only about ten minutes time and G.W. Van Horne less time.”

In September 1889, Clark addressed “fully 1,000 people” at Ottumwa:

[F]rom the 22d of September, ’62, to the first of January, ’63, five million of bondsmen made free by this proclamation, and we rejoice to-day, this proclamation of the martyred and sainted Lincoln, and the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the federal constitution have become a part of the fundamental laws of the land; the proclamation declaring their ratification has been promulgated to the world.

Journal editorial, January 2, 1863: “So magnificent a New Year’s gift has never till now been heard of. An act of single man more just, more right, more sublime, we will search for in vain among all the records of history. … Emancipation has been declared. The year comes upon us to commence the cycle of a better, nobler era—an epoch which we may be proud of having witnessed, and to which the coming generations will look back as we do upon the 4th of July, 1776.”

This year, more than ever before, I saw publicity for Juneteenth events and exhibits in our area. I didn’t attend any, but I resolve to do better next year.

Next time: Aleck’s prize squash

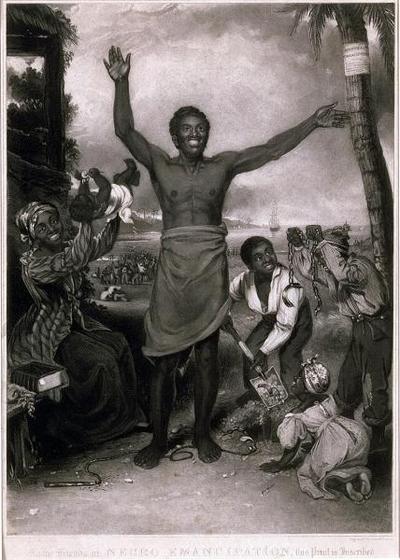

Top image: Engraving by David Lucas after a painting by Alexander Rippingille (1796-1858), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.