This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

When the nation celebrates our 250th anniversary in 2026, let us observe Alexander Clark’s 200th birthday, too.

By 1890, when President Benjamin Harrison appointed him minister to Liberia, the Muscatine man was known throughout the U.S. as “the colored orator of the West.” His speeches and writings exhorted Americans to live up to the all-are-created-equal demands of the Declaration of Independence. It was one of his favorite themes.

People ask what Clark might have said about this or that, were he with us today. From all evidence I’ve seen, I am pretty sure he would quote stirring passages from the report of President Trump’s 1776 Commission, but he would not embrace the whole thing.

I’m also pretty sure he would skewer his fellow Republicans’ weaponizing of 1776 for their school-board battles against threats they perceive from so-called Critical Race Theory. (Unless he’d become a Democrat.)

Several readers warned me we won’t be able to tell the stories of Iowa’s Black History if we give in to lawmakers who would block every teaching that might make white kids feel bad. But I digress.

I’ll just say I believe Clark would stand with Waterloo native Nikole Hannah-Jones as surely as he championed fellow Black journalist Ida B. Wells when her reports of lynching shocked readers of their time.

In her preface to the controversial anthology The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story, Hannah-Jones writes: “Even as a teenager, I understood that the absence of 1619 from mainstream history was intentional. People had made the choice not to teach us the significance of the year.”

Along with other Muscatine folks, I attended her talk and book signing at her old high school last November. It was my second time hearing her speak. Please learn more about our fellow Iowan if you aren’t proud of her yet.

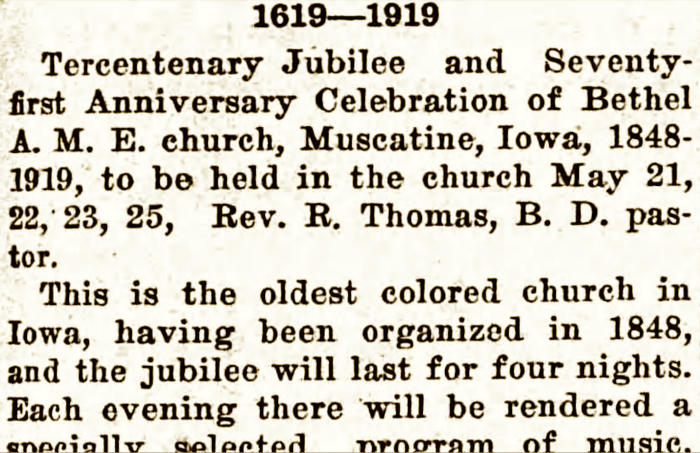

Lest you fear “reframing” our shared story at 1619 might be a new and divisive idea, I refer you to the full name of a four-day event that got lots of attention in Iowa in 1919: the Tercentenary Jubilee and Seventy-first Anniversary Celebration of Bethel A.M.E. Church.

From the Muscatine Journal (March 25): “The occasion will commemorate the landing of the first negroes in America three hundred years ago, and the establishment of the African M.E. church in Muscatine, almost three quarters of a century ago.”

From the Iowa Bystander (March 28): “This is the oldest colored church in Iowa, having been organized in 1848. … One among the pastors of note who served this church was Rev. R.H. Kain [sic], a man of great energy and decided ability as a ready and eloquent speaker. He was sent to Congress and served two terms and was later elected fourteenth Bishop of the A.M.E. Church. He died in 1887 in Washington, D.C. … Some of the pioneer members were Hon. A. Clark, afterwards U.S. minister to Africa, and who died in Africa in 1891, and B. Mathews. Among the members who came with the inflow after the war were R. Hainey, Rosetta Watson, Abram Seabrooks, Peter Townley and Sawyer Lamb.”

Readers who are following along will recall I introduced Bishop Cain as an Iowa pioneer earlier. Watch for these other names to reappear as I dig further into the story of Alexander Clark’s historic congregation.

From the Journal (May 23): “The pageant constituted the second night’s program of the tercentenary jubilee…. The negro race was traced from the early Bible to African days, through the dark days of slavery up to the American negro citizen of today. Three hundred years ago the first negro arrived at Jamestown, Va. Several southern plantation scenes in the days of slavery were shown to illustrate the event and its results, and the characters sang many of the songs of the plantation ‘darkies’ of that day.”

Speaking of “centering” slavery.

The third night’s speaker was the Rev. D.W. Brown of Oskaloosa, Bethel’s pastor in 1912 and 1913. “He told of many interesting experiences in his early life when he was a slave and declared that success only crowned the efforts of those who took pride in themselves and their work.”

I’ll tell you what got more attention than that four-day celebration, though. A one-week run of D.W. Griffith’s cinematic blockbuster “The Birth of a Nation” got huge attention in 1916. Along with a full-page ad, there was unabashed ecstacy from the Democrat-run Muscatine News-Tribune and only slightly less enthusiasm from the Republican Journal, which inserted a subhead claiming “Not Reflection on Negroes.”

Brought back to the A-Muse-U in 1922, the Journal reported: “This big spectacle is being shown here in its entirety, with its accompanying symphony orchestra, its effect paraphernalia and its trained mechanicians…down to the smallest detail that amazed New York and other cities.”

Speaking of divisive narratives.

Top image: From The Bystander, March 28, 1919.