Dan Piller was a business reporter for more than four decades, working for the Des Moines Register and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. He covered the oil and gas industry while in Texas and was the Register’s agriculture reporter before his retirement in 2013. He lives in Ankeny.

President Donald Trump renewed his eight-year tariff war last weekend by declaring tariffs of 25 percent on most goods from Mexico and Canada (10 percent on Canadian oil) and 10 percent on China. No sooner had the war been declared than we had a 30-day truce as Mexico and Canada promised various reinforcements of their border that supposedly will stanch the flow of fentanyl into the U.S.—policies both countries had announced weeks earlier.

Trump famously told us eight years ago that trade wars are “easy to win.” But if they’re so easy, why are we still fighting them eight years later? U.S. armed forces needed just half that time to subdue Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan in World War II.

Trump and his MAGAtoids can claim short-term victories with the Mexican and Canadian truces. But bigger hills remain to be seized. China might not be so easy to bully. Neither will be the European Union. To those of us of advanced ages, the 30-day truce was reminiscent of the occasional truces during the Vietnam War, when hopes were raised around the world only to be shattered by the resumption of bombings and guerilla ambushes.

TRADE WAR COULD BECOME A QUAGMIRE

Those young, eager Trump acolytes on Fox News might well spend time by googling “Vietnam War” and “Lyndon Johnson” as a possible preview of what may be in store for their hero. It’s possible to envision buddies Trump and Vladimir Putin at future summit meetings sharing doleful commiserations of their respective quagmires; Ukraine and trade.

Continuing the military analogy, Iowa is at the point of this latest front in the trade war. Mexico is the largest buyer of American corn. Canada, like Mexico, annually buys almost $30 billion of U.S. grain, meat, processed foods, and machinery. It also is the largest foreign buyer of ethanol. In addition, Canada supplies up to 20 percent of oil and diesel that is refined into Iowa’s motor vehicle and farm implement tanks.

Trump told reporters on February 2 that “We may have short-term a little pain” as prices rise due to tariffs, adding, “And people understand that.” But one of his biggest supporters, American Farm Bureau Federation president Zippy Duvall, outlined the limits of farmers’ “understanding” Monday with a plaintive cry of pain:

Farm Bureau members support the goals of security and ensuring fair trade with our North American neighbors and China, but, unfortunately, we know from experience that farmers and rural communities will bear the brunt of retaliation. Harmful effects of retaliation to farmers ripple through the rest of the rural economy.

In addition, over 80% of the United States’ supply of a key fertilizer ingredient — potash — comes from Canada. Tariffs that increase fertilizer prices threaten to deliver another blow to the finances of farm families already grappling with inflation and high supply costs.

On a less economically serious note, Trump’s trade policy could set back Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.’s drive to “make America healthy again” (presuming he can be confirmed as Secretary of Health and Human Services). About 60 percent of U.S. fruits and vegetables are imported, so tariffs may make those healthy choices more expensive.

UNCERTAIN PROSPECTS FOR HELP FROM WASHINGTON

As recent cabinet confirmation hearings plodded along, farm state U.S. senators have managed to do little to comfort the folks back home. They did extract a pledge from Secretary of Agriculture-designate Brooke Rollins that the Trump administration will again compensate farmers. During his first administration, Trump forked over about $28 billion in taxpayer-funded “trade mitigation payments” to farmers, when the first round of his tariff war drove corn and soybean prices under the breakeven water line. Rollins promised “something similar” if confirmed.

In December, Congress kicked in another $10 billion to farmers as part of a federal disaster relief package, putting the state of farmers in the same dire category as hurricane and wildfire victims. Farmers who have buried their self-consciousness about taxpayer aid with waves of “Farmer Appreciation” and “America Needs Farmers” promotions have reason to squirm about being more dependent on federal assistance than ever.

In Washington, farsighted agriculture lobbyists can only wonder if a political reckoning for taxpayer assistance to agriculture might be pending. For two years in a row, Congress missed the deadline for passing a new Farm Bill. The 2018 Farm Bill was extended for a second time. Meanwhile, House Speaker Mike Johnson hasn’t brought a new version to the floor, probably because of tightfisted “Freedom Caucus” members.

Agriculture and its farm state reps in Congress may sleep less easily these days. Although the Washington-obsessed cable news networks seem unaware, the U.S. now has a once-unthinkable trade deficit in agriculture that for 2024-25 will near $45 billion. Almost 18 percent of an American family’s food budget now goes for foreign produce, cheeses, nuts, wines, and beers.

Farmers who normally spend the winter months pondering the distribution of corn and soybean plantings on Iowa’s 24 million cultivatable acres, now have more heavy thinking to do. Corn prices exceeded $7 per bushel in 2021, when driven artificially high by Chinese purchases needed to rebuild their disease-ravaged hog herds. Then corn fell to barely $3 per bushel when China turned its attentions back to its new best corn and soybean friend, Brazil.

Since mid-2024, corn has staged a slow-but-steady rally to almost $5 per bushel. Some traders said the trend reflected international buyers stocking up before the expected Trumpian tariff onslaught. Soybean prices similarly fell from giddy highs of plus-$15 per bushel to under $9 per bushel last year, but scratched above $10 in the first weeks of 2025.

If those prices prove durable through the 2025 crop trading season, Iowa farmers might fashion a modestly profitable year after two consecutive years of industry-wide losses. But another possible scenario is a repeat of their collapse in 2018-2019 when Trump opened his first trade war with China and Mexico. If that comes to pass, then both grain and livestock production agriculture—which are heavily dependent on exports—will sink into the same dismal slog that the auto industry experienced a half-century ago. German and Japanese carmakers won the hearts of American drivers in those days with cars that weren’t visually attractive, but were cheap and fuel-efficient.

FARMER’S BIGGEST FOREIGN MARKETS COULD DISAPPEAR

Many farmers have shrugged off the tariff imbroglios with their “we’ve seen this before” attitude. But those whose knowledge of the sector goes beyond Fox & Friends understand that for agriculture, the world of 2025 is a much different place than at any other time in history. Whereas foreign markets once could be lost and reclaimed fairly easily, U.S. farmers now face the prospect that their biggest markets for grain and meat products may disappear for good.

As recently as the middle of the first decade of the 21st century, the U.S. controlled more than 60 percent of the world’s grain exports, and Iowa farmers boast that they “feed the world” was not idle. But since 2005, agricultural rivals have emerged to not just threaten, but take away America’s dominance of world grain markets. Trump’s tariffs will likely put the thumb on U.S. world grain market share, which fell below 40 percent by 2023.

Most of the world may not be fans of Russian President Vladimir Putin, but he has turned the miserably inadequate performance of Soviet-era agriculture into the world’s largest wheat exporter. Iowans may sputter at the thought, but much of the livestock-producing world considers wheat a perfectly good feed for cattle and hogs.

As for corn, Brazil has taken advantage of deforested land and two annual growing seasons to increase its share of world exports from 6 percent in 2005 to 30 percent by 2023. In the process, Brazil has passed the U.S. as the world’s largest corn exporter. China, having learned its Trump-imposed lesson about American export dependability, is cheering the Brazilians on with a new agricultural treaty signed in 2022. A $1.5 billion Chinese-owned seaport on the Pacific coast at Chancay, Peru will smooth the trip to China for Brazilian and Argentinian corn and soybeans, grain that the Chinese won’t need to buy from Iowa farmers.

(Some of the Trump-inspired grumbling about the supposed “Chinese control” of the Panama Canal may be rooted in the frustration that Brazilian and Argentinian corn and soybeans pass through the American-built canal en route to China, aided by Chinese-built ports and terminals adjacent to the canal.)

It goes without saying that the Chancay port also can be used to ferry grain from South America to Mexico’s tortilla and taco processors, heretofore largely dependent on American corn farmers. Some of the recent run-up in corn and soybean prices has been laid at the feet of dry conditions in South America this year. But savvy agrarians know better than to base long-term plans on bad weather somewhere else. As longtime Des Moines Register farm editor Don Muhm frequently cautioned younger reporters earnestly grinding out drought stories, “the paper the that carries that drought story likely will be wet from rain.”

If the effects of the tariff war were confined just to the estimated 40-50,000 working farmers in rural Iowa counties, the state could endure nicely. But more than 2,500 farm implement and tire manufacturing workers in Waterloo, the Quad Cities, Ottumwa, and Des Moines have been laid off due to unpromising outlooks for the sale of expensive farm tractors, combines, planters, and sprayers. The likely further consolidation of agriculture, which has already stripped much of rural Iowa of its young talent, could throw ominous shadows over the cubicles of insurance analysts in downtown Des Moines, Cedar Rapids, and Davenport.

CONTRA TRUMP, PAST TARIFFS DIDN’T FUEL ECONOMIC SUCCESS

Exactly how Trump, whose previous business ventures were real estate development and reality television, came to love tariffs as an agent of prosperity is a mystery. He cited William McKinley during the 2024 campaign and in his inaugural address. As example of an orthodox Republican for his time, McKinley would do well enough. But when Trump claimed in his inaugural address that McKinley “made our country very rich through tariffs,” well, golfer Trump hit that one into the woods.

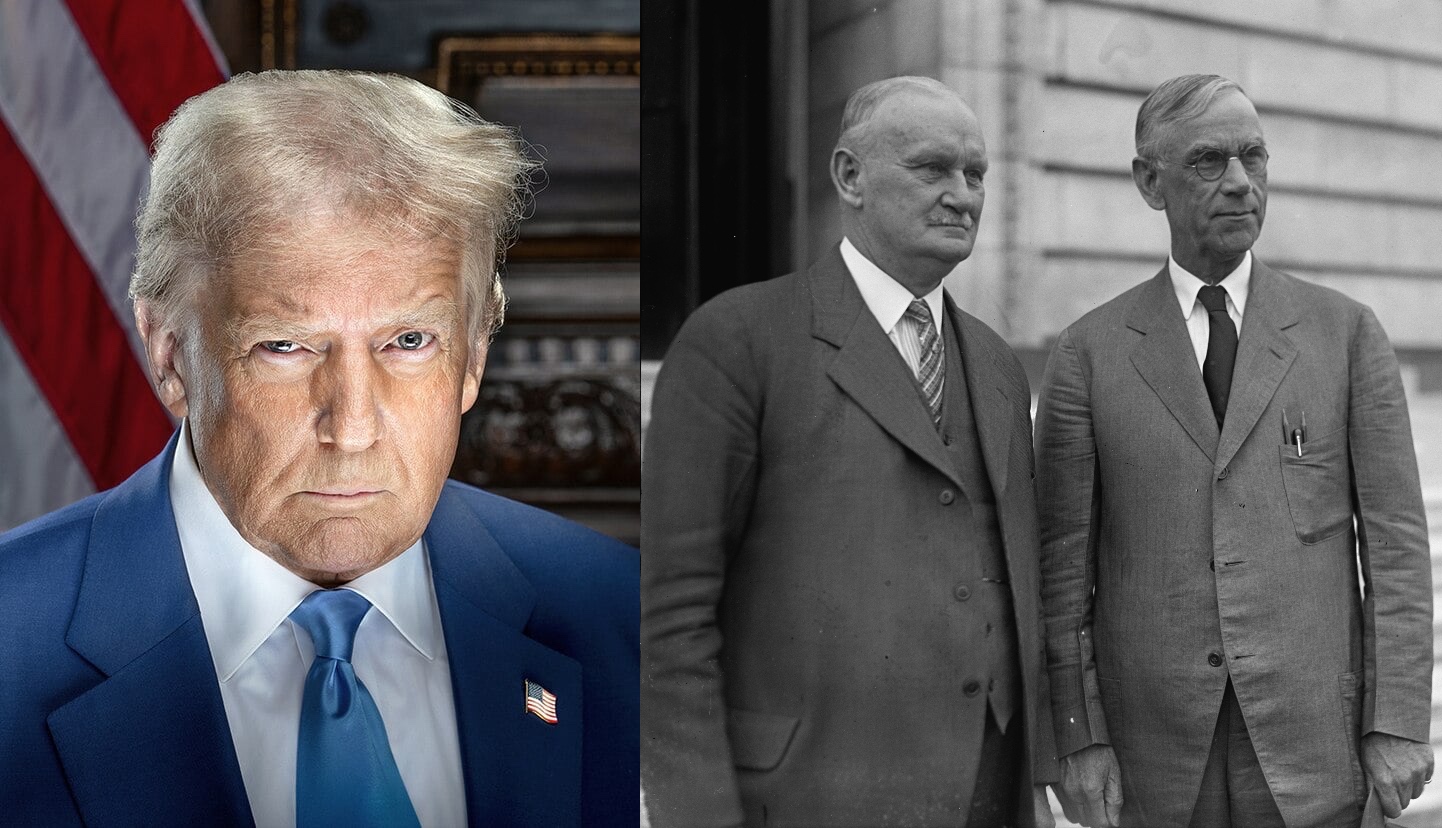

Portrait of William McKinley

McKinley used his position as chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee in 1890 to push through a tariff bill that raised duties from an average of 39 percent to just under 50 percent. Tariffs weren’t a radical invention; before the income tax was legalized in 1913, customs duties were the federal government’s prime method of raising money.

But the McKinley Tariff was a failure both politically and economically.

The higher prices caused by the tariffs were unpopular and resulted in McKinley’s Republican Party losing its congressional majority later in 1890. The backlash bounced Republican President Benjamin Harrison from the White house in 1892 in favor of Grover Cleveland.

Cleveland, who until Trump was the only president to be elected to two nonconsecutive terms, suffered bad timing in a manner that foreshadowed Herbert Hoover in 1929. On May 5, 1893—a mere two months after Cleveland’s inauguration—a 24 percent drop in the New York Stock Exchange set off what became known as the Panic of 1893. (In the 20th century the term “depression” replaced “panic” in the economic context.)

The remainder of the decade was known not for great wealth, as Trump asserted in his misguided inaugural history lesson. Rather, the 1890s brought widespread business and farm failures. Unemployment reached 18 percent by 1898. Political historians remember that period for the rise of the agrarian Populist movement, which was culturally and economically far removed from the plutocracies of McKinley, Cleveland and, in our time, Trump.

Cleveland was denied nomination for a third term in 1896 by Nebraska firebrand orator William Jennings Bryan and his “Cross of Gold” speech. McKinley was the Republican nominee, the upholder of sound money, the gold standard and tariffs. To beat the dashing Bryan, Wall Street moneymen had to outspend the Democrats by ten-to-one but they pushed the plodding McKinley to victory, and the U.S. economy proceeded wobbly back to prosperity.

Fuel for recovery came not from tariffs, but by immigrants who flooded eastern cities and helped build a new generation of skyscrapers. Extra capital came from newly-discovered gold in the Yukon, crucial in those days when the U.S. economy still ran on the gold standard.

REPUBLICANS RETURNED TO TARIFFS IN 1920S

The advent of the federal income tax in 1913 removed the need for tariffs as a government revenue-raiser. But the Republican Party’s old habit of protectionism returned in 1922 with the Fordney-McCumber tariff, which raised duties by 40 percent. The explosion of consumerism in the “Roaring Twenties,” led by the automobile and radio industries, spared the cities from the worst effects of the new tariff. However, farmers began what was to be their own 20-year Great Depression as their crucial export markets disappeared.

The weakness of agriculture in the 1920s was an early economic crack that led to the stock market crash in October 1929. Seven months later, in May 1930, a Republican-led Congress responded with the Mother of All Tariffs, the Smoot-Hawley tariff that raised duties by 50 percent. The act was named for U.S. Representative Willis Hawley of Oregon and Senator Reed Smoot of Utah.

Willis C. Hawley (left) and Reed Smoot standing together on April 11, 1929. The following year, they led efforts to pass the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. Photo from the Library of Congress is available via Wikimedia Commons

Like its predecessors, Smoot-Hawley was both a political and economic failure. Exports fell by two-thirds by 1932, and historians and economists widely cite Smoot-Hawley as a factor that made the Great Depression unnecessarily calamitous. Both Smoot and Hawley lost their seats in the 1932 election, a plebiscite that put Democrats in control of Congress for four decades and installed Franklin D. Roosevelt in the White House for more than twelve years.

TRADE POLICY CAUSED FARM TURMOIL IN TRUMP’S LIFETIME

If Trump obviously has misread (or never read) history in his admiration of McKinley and tariffs, his own memory should be a guide. President Jimmy Carter responded to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 by embargoing grain sales to the USSR. The embargo was a stake through the heart of Midwestern grain agriculture, which in the 1970s had profited lustily from sales of grain to the Soviets.

Carter had other troubles in his 1980 reelection campaign, most notably the seizure of hostages at the U.S. embassy in Tehran, Iran. But the ensuing “Farm Crisis” touched off by the grain embargo helped pad Ronald Reagan’s landslide. Farmland prices in Iowa, which had reached records in 1979, would not return to the same inflation-adjusted levels until 2009.

So, the historical and philosophical origins of Trump’s obsession with tariffs remain obscure, beyond their obvious use as leverage against countries he doesn’t like (which seems about everybody these days). Tariffs may also be popular with organized labor, angered by American jobs shifted overseas.

History shows that while tariff promises can help politicians win elections, their ensuing effects are toxic for those politicians and their parties. Trump would do well to have a resident historian close at hand. He’ll need one.

5 Comments

Thank you, Dan

Thank you for this lesson in agricultural economics and tariff history. This leaves me again wondering “What is the matter with farmers and rural residents?” They continue to vote overwhelmingly against their own economic best interest. It is perfectly obvious that tariffs against our best trading partners are a disastrous idea, but Trump put them right out there in the campaign and he still won their votes. You didn’t even mention the impact of mass deportations on livestock production and meat packing in Iowa. Similarly disastrous. The pull of cultural issues is even stronger than the pull of economic issues.

Miketram01 Fri 7 Feb 9:51 AM

What a great history lesson

Too bad the Republican legislators won’t let Iowa students receive such a lesson.

Wally Taylor Fri 7 Feb 11:20 AM

A side effect

Industrial agriculture is already doing awful things to the life support systems of the planet. The damage includes the massive farm pollution rolling through the Cornbelt, the destruction of the important Cerrado biome in South America, and far more. Trump’s agriculture-related decisions could make the situation significantly worse.

PrairieFan Fri 7 Feb 12:20 PM

time will tell

Time will tell whether DJT was truly serious about tariffs or if they were a negotiation ploy. After the inflation ridden Biden/Harris era hard-working Americans have had enough of runaway inflation. Watched Kamala Harris uncensored CBS interview and James Carville was spot on referring to her as a “7th string quarterback.” Justified my vote for RFK Jr. for POTUS.

ModerateDem Fri 7 Feb 2:42 PM

vote for RFK

Nothing could justify a vote for RFK, jr.

bodacious Fri 7 Feb 5:48 PM