Rick Morain is the former publisher and owner of the Jefferson Herald, for which he writes a regular column.

President Joe Biden’s recent pardon of his son Hunter Biden has reignited the debate over the presidential pardoning power. And argument over this constitutionally protected prerogative of the president will not go away with Donald Trump’s return to power next month. Trump already has used the pardoning power for the benefit of his political cronies during his first term (2017-2021).

Biden is reportedly mulling whether he should go further in light of Trump’s threats to bring charges against some of his political enemies after he returns to office in 2025. In light of those threats, Biden is reportedly considering preemptive pardons for former U.S. Representative Liz Cheney, former Representative and now Senator Adam Schiff, former Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Anthony Fauci, and General Mark Milley, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Trump has butted heads with all four of the above in recent years. Preemptive pardons for one or more of them would assure they would not face prosecution for actions they have taken in opposing the president-elect, whether legitimate or not.

Hunter Biden received his father’s official clemency not only for federal tax and gun charges for which he was awaiting sentencing, but also for any federal crimes he might possibly have committed between January 1, 2014, and December 1, 2024. President Biden granted the pardon despite his promise not to do so, a move that dismayed many of his supporters.

The pardon for the possible crimes of those eleven years is an example of “preemptive” pardoning, an unusual use of the pardoning power but not unprecedented.

After the Civil War, President Andrew Johnson pardoned large numbers of Confederate officials and soldiers. President Gerald Ford pardoned former President Richard Nixon after Watergate. President Jimmy Carter pardoned Vietnam draft dodgers. President George H.W. Bush pardoned former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger. Trump pardoned Sheriff Joe Arpaio of Phoenix, among others, who was charged and convicted, but had not yet been sentenced.

A strong case can be made to eliminate or restrict the president’s pardoning power. It would be difficult, since the Constitution states that the president “shall have Power to Grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” The power is absolute; there’s no constitutional provision for overriding it. Changing the power would require a constitutional amendment.

When the Founders drafted the Constitution in the summer of 1787 in Philadelphia, they debated whether to limit the president’s ability to pardon. They considered making treason an exception to that power, and also mulled requiring Senate approval of any presidential pardon. But neither suggestion survived the Founders’ debates.

The pardoning power is so strong that it remains unclear whether a president can pardon himself for federal offenses. That possibility seems illogical to most Americans, but the question has yet to be decided by the courts. It will remain an open one until some president—might it be Trump?—initiates a self-pardon. At that point, the question will have to work its way through the judicial system.

The U.S. Supreme Court may have opened the door for a self-pardon when it ruled in July that the president is immune from prosecution for official acts he or she takes, even if those acts break the law.

The Founders’ reasoning for writing an unlimited pardoning power into the Constitution sounds quaint today. They created the power to pardon as a check against unfair or erroneous court decisions. They anticipated that a president who went beyond that boundary, using the pardon to keep his or her associates, friends, or family members out of jail, would face impeachment.

That theory has been proven wrong, as presidents of both parties have shown little compunction about doing precisely what the Founders thought would not happen. To my knowledge, Congress has never considered impeaching a president for issuing pardons, whether justified or not.

To put it bluntly, the pardoning power enables a president to invalidate any federal court conviction, no matter how justified. That surely goes beyond what the Constitution’s authors intended. It certainly upends the balance of power among the three branches of government.

Even though altering the pardoning power would be a steep uphill climb, some members of Congress have attempted to do it in recent years. Just last week, Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson promised that reform of the pardoning power system is “on the way, and it cannot happen soon enough.” That remains to be seen: Johnson appears totally devoted to President-elect Trump, and seems unlikely to limit Trump’s power in any way.

Bottom line: for the foreseeable future, presidents will continue to enjoy unlimited power to grant clemency, commutations, amnesty, and pardons to anyone convicted of a federal crime or in jeopardy of such a conviction.

In hindsight, the pardoning power looks to me like an error on the part of the Constitution’s drafters. It has turned out to be not a benign limitation on erroneous courts, but rather an enormous tool for autocracy, if a president chooses to use it in that way.

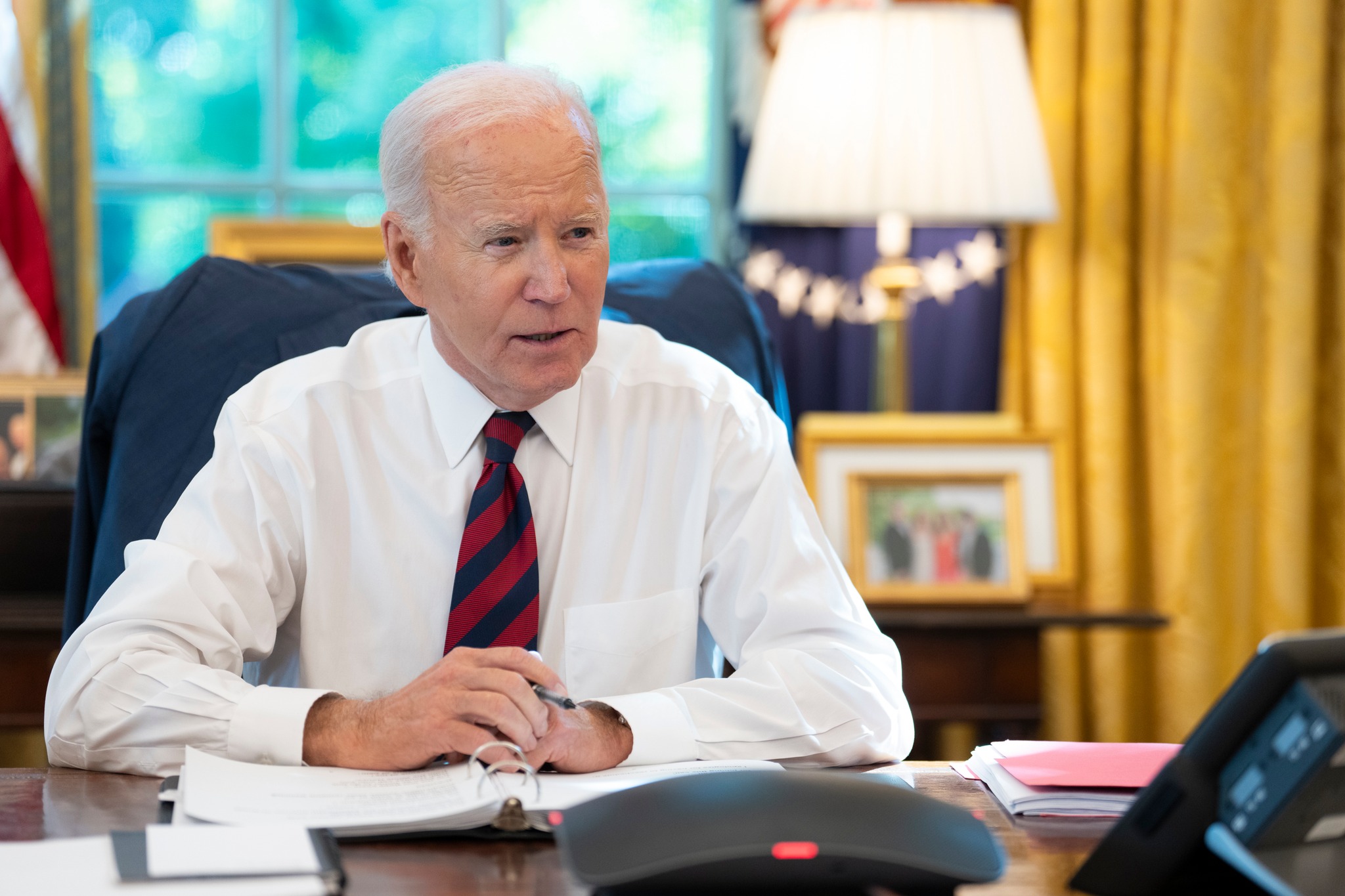

Top image: President Joe Biden participates in a phone call with Jewish faith leaders, rabbis and members of the Jewish community for the High Holidays, Wednesday, October 9, 2024, in the Oval Office. (Official White House Photo by Cameron Smith, originally published on the president’s official Facebook page)

1 Comment

It just happened

“The pardoning power is so strong that it remains unclear whether a president can pardon himself for federal offenses.”

The blanket pardon to Hunter is President Biden pardoning himself. Hunter Biden just got a blanket pardon for the 2014-2024 period. He was the strawman who brought $20 millions of bribery money to the Biden family from Romania, Kazakhstan, Russia, Ukraine, and China. And the corruption deals started in 2014.

This is supported by a 2023 public congressional report: “Since taking the gavel in January, the Committee on Oversight and Accountability has accelerated its investigation of the Biden family’s domestic and international business practices to determine whether the Biden family has been targeted by foreign actors, President Biden is compromised, and our national security is threatened. Records obtained through the Committee’s subpoenas to date reveal that the Bidens and their associates have received over $20 million in payments from foreign entities.

Below is a timeline that details key dates in our investigation.

The main points of interest are:

1) Romania: On September 28, 2015, Vice President Biden welcomed Romanian President Klaus Iohannis to the White House. Within five weeks of this meeting, a Romanian businessman involved with a high-profile corruption prosecution in Romania, Gabriel Popoviciu, began depositing a Biden associate’s bank account, which ultimately made their way into Biden family accounts. Popoviciu made sixteen of the seventeen payments, totaling over $3 million, to the Biden associate account while Joe Biden was Vice President. Biden family accounts ultimately received approximately $1.038 million. The total amount from Romania to the Biden family and their associates is over $3 million.

2) China- CEFC: On March 1, 2017—less than two months after Vice President Joe Biden left public office—State Energy HK Limited, a Chinese company, wired $3 million to a Biden associate’s account. This is the same bank account used in the above “Romania” section. After the Chinese company wired the Biden associate account the $3 million, the Biden family received approximately $1,065,692 over a three-month period in different bank accounts. Additionally, the CEFC Chairman gives Hunter Biden a diamond worth $80,000. Lastly, CEFC creates a joint venture with the Bidens in the summer of 2017. The timeline lays out the “WhatsApp” messages and subsequent wires from the Chinese to the Bidens of $100,000 and $5 million. The total amount from China, specifically with CEFC and their related entities, to the Biden family and their associates is over $8 million.

3) Kazakhstan: On April 22, 2014, Kenes Rakishev, a Kazakhstani oligarch used his Singaporean entity, Novatus Holdings, to wire one of Hunter Biden’s Rosemont Seneca entities $142,300. The very next day—April 23, 2014—the Rosemont Seneca entity transferred the exact same amount of money to a car dealership for a car for Hunter Biden. Hunter Biden and Devon Archer would represent Burisma in Kazakhstan in May/June of 2014 as the company attempted to broker a three-way deal among Burisma, the Kazakhstan government, and a Chinese state-owned energy company.

4) Ukraine: Devon Archer joined the Burisma board of directors in spring of 2014 and was joined by Hunter Biden shortly thereafter. Hunter Biden joined the company as counsel, but after a meeting with Burisma owner Mykola Zlochevsky in Lake Como, Italy, was elevated to the board of directors in the spring of 2014. Both Biden and Archer were each paid $1 million per year for their positions on the board of directors. In December 2015, after a Burisma board of directors meeting, Zlochevsky and Hunter Biden “called D.C.” in the wake of mounting pressures the company was facing. Zlochevsky was later charged with bribing Ukrainian officials with $6 million in an attempt to delay or drop the investigation into his company. The total amount from Ukraine to the Biden family and their associates is $6.5 million.

5) Russia: On February 14, 2014, a Russian oligarch and Russia’s richest woman, Yelena Baturina, wired a Rosemont Seneca entity $3.5 million. On March 11, 2014, the wire was split up: $750,000 was transferred to Devon Archer, and the remainder was sent to Rosemont Seneca Bohai, a company Devon Archer and Hunter Biden split equally. In spring of 2014, Yelena Baturina joined Hunter Biden and Devon Archer to share a meal with then-Vice President Biden at a restaurant in Washington, D.C. The total amount from Russia to the Biden family and their associates is $3.5 million.

Beyond this timeline, here are links to our First, Second, Third, and Fourth Bank Memorandums that provide detailed descriptions and show actual bank records and wires. (…)”

Karl M Thu 12 Dec 5:13 AM