Herb Strentz was dean of the Drake School of Journalism from 1975 to 1988 and professor there until retirement in 2004. He was executive secretary of the Iowa Freedom of Information Council from its founding in 1976 to 2000.

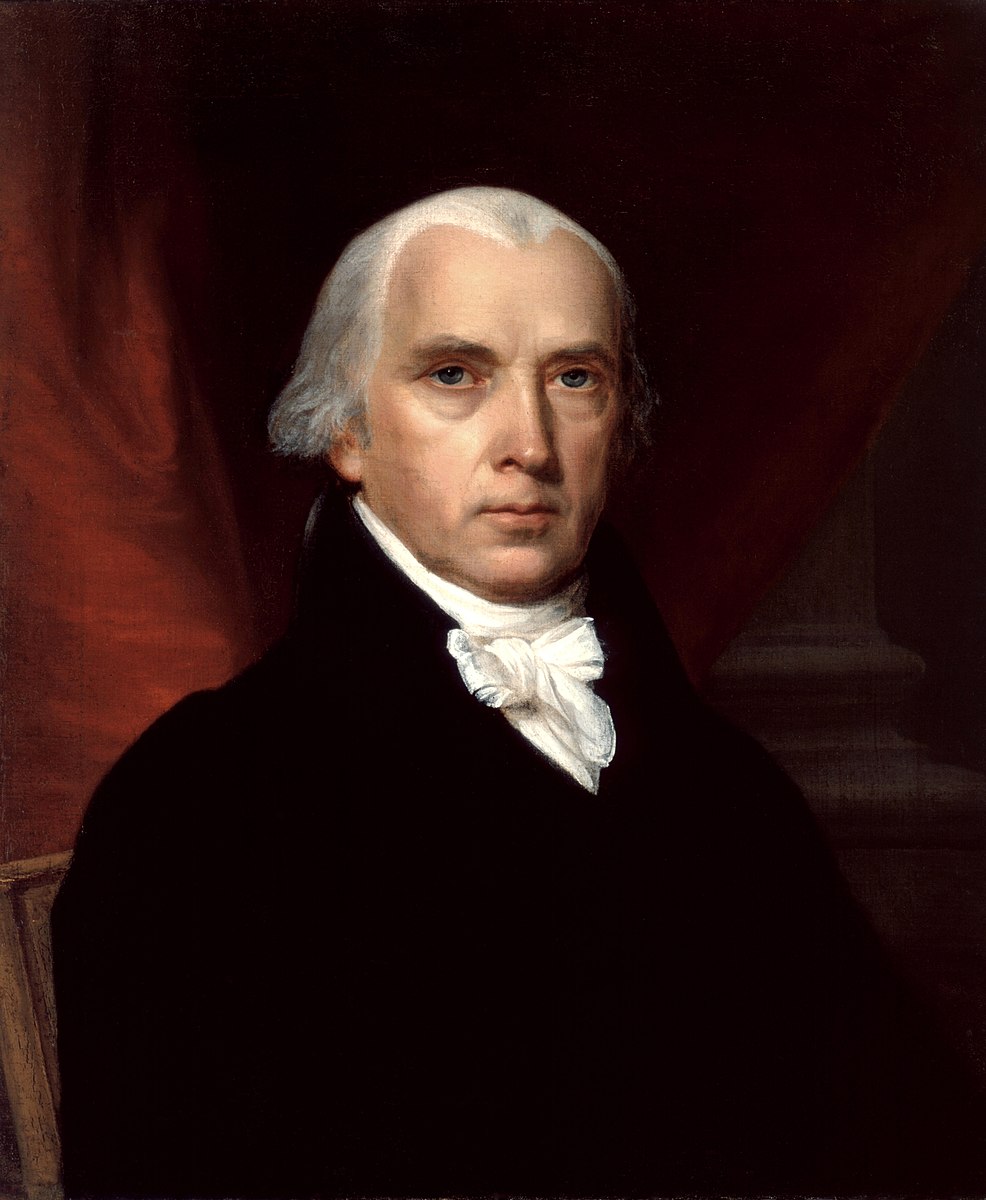

James Madison, a key figure in adopting our Bill of Rights and our fourth president from 1809 to 1817, seemed to foresee the Donald Trump phenomenon and the farce and looming tragedy of the 2024 election.

In 1822, Madison wrote, “A popular Government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy; or perhaps both. Knowledge will for ever govern ignorance: and a people who mean to be their own Governours, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.”

Journalists cite Madison’s concerns as an argument for access to government meetings and public records so a “watchdog press” can hold government accountable and also serve as “The Fourth Estate” of government.

The context for Madison’s warning, however, was praise for public schools and his relief that, “The liberal appropriations made by the Legislature of Kentucky for a general System of Education can not be too much applauded.”

(Those rightly troubled by how Governor Kim Reynolds, the Republican-controlled Iowa legislature, and the MAGA movement have attacked public schools should feel free to use the Madison quote.)

The catalyst for this post, however, is the relevance of Madison’s fears of “farce” and “tragedy” with regard to the presidential election — including the Minneapolis Star-Tribune’s recent refusal to offer its readers an endorsement for president.

A national trend affecting “The newspaper Iowa depends upon”

You’d think the now locally owned Star-Tribune—once under the same Cowles family ownership as the Des Moines Register—might have some insights worth sharing about Minnesota Governor Tim Walz, the running mate of the Democratic presidential nominee, Vice President Kamala Harris.

We’ll return to Madison and the role of the press as “The Fourth Estate” and a “watchdog” of government. But let’s begin with the decline of editorial commentary.

For some insight, I checked with the respected Poynter Institute in St. Petersburg, Florida, and heard back from Rick Edmonds, who for several years has been tracking the decline of papers generally with some focus on cutbacks in editorials—commentaries that for almost two centuries have been called the heart and soul of newspapers.

Edmonds wrote in June 2022 about the decline of editorials among Gannett-owned newspapers. In March of that year, the Gannett-owned Des Moines Register announced it was cutting back its daily opinion section with editorials and letters to the editor to only Sundays and Thursdays. In effect that has meant cutting back from several hundred editorials a year to 52 on Sundays and, in practice, to fewer than a dozen on the 52 Thursdays. The decline in published letters to the editor likely would be even greater.

Edmonds reported on reasons that Amalie Nash, a former editor of The Des Moines Register, gave for the cutback in editorials. Nash was Gannett’s senior vice president for local news and audience development. She joined the non-profit National Trust for Local News this year.

Not the best of reasons

One of Gannett’s justifications for reducing editorial comment was: “Readers do not want to be lectured at or told what to think.” To put it another way: “We should not have poorly written, off-base editorials that turn off readers. But rather than improve on sharing our perspective, let’s just do away with most editorials.”

Another reason: “Routine editorials, point-of-view syndicated columns…consistently turn up as the most poorly read articles online.” To put a different spin on it: it shouldn’t be surprising that online readers click more often on sports and the comics than on editorials. But if a well-written and soundly based editorial hits home with some citizens and just a few decision makers, that warrants running it.

These reasons for cutbacks seem more like expedient excuses for saving money, as opposed to decisions made with the goal of providing more value to readers.

Edmonds wrote, “I received tips or complaints from a half-dozen retired editors, who see the changes as a veiled cost-cutting move and abdication of the principle that a newspaper needs to stand for something and say so regularly.”

The article also offers comments from Lucas Grundmeier, editor of the Des Moines Register opinion pages. To their credit, he and executive editor Carol Hunter have worked to offer helpful editorial perspectives outside the Sunday-Thursday constraints.

Curiously, while it is the press that has lauded itself as a “watchdog” of democracy, it was not the press that characterized itself as “The Fourth Estate.” Rather it was government observers in England around the time of Madison’s benchmark 1822 letter.

Back then the English appended the press’s status as “The Fourth Estate” to the three estates common in England and European nations: the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners. In England that would be the Anglican Church (lords spiritual), the crown (lords temporal) and parliament.

And, as good fortune would have it, Madison’s letter and “The Fourth Estate” notion were followed a few years later by the precursor of newspapers of the 20th and 21st centuries—the “Penny Press” of the 1830s and 1840s.

The Penny Press was just that, priced at a penny an issue instead of 6 cents to attract readers—and welcoming immigrants so castigated by MAGA today. The first penny paper was Ben Day’s New York Sun in 1833. Soon following were Horace Greeley and the New York Tribune, Henry Raymond and the New York Times, and James Gordon Bennett of the New York Herald.

The answer is in your hands

The “Fourth Estate” notion fit in nicely with those editors and even more so with publishers like Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst in the late 1890s and early 1900s. What a glorious time for the press! For a century or more, print journalism had the hometown and beyond audience to itself and could readily cope with the arrival of broadcasting as a fellow member of the Fourth Estate 30 or 40 years into the 20th century.

So far, however, the print folks have not coped as well with the internet, a dominant purveyor of information and, sadly, misinformation, and a gobbler of advertising revenue. The number of daily newspapers is expected to drop by more than a third from 1,748 in 1970 to fewer than 1,200 this year.

The 15th and 16th centuries helped usher in thoughts and technology. Centuries later, the printing press helped foster democracies, as better-informed publics sought to govern themselves.

The 21st century may usher us out of self-governance, thanks in part to misinformed publics driven by self-interest and fear.

Rays of hope are difficult to discern if we probe the internet and other sources for information about how bad things are. In an oddball way, one can find hope in most of the obituaries in the Sunday New York Times. They often tell of lives well lived, and people who made so many contributions and accomplished so much for others that you wonder why you’ve never known about them.

Such people may yet help our society escape the divisiveness and fears Trump foments.

There’s the fable about the youth who will confront a supposed wise person about whether the bird in his hand is alive or dead. Depending upon what the wise one says, the kid will free the bird or crush it to prove the wise one wrong.

The wise response to the kid is, “The answer is in your hands.”

So it will be, come November 5.

For my part, it was good to revisit the 2005 book by Iowan Michael Gartner and the Gannett Newseum: Outrage, Passion & Uncommon Sense: How Editorial Writers Have Taken on the Great American Issues of the Past 150 Years.

As the late public television news anchor Robert MacNeil (1931-2024) said of the book, “May it stiffen the spines of editorial writers timidified by dying newspaper competition.”

5 Comments

Excellent

This is an eye opening piece on why journalism matters. Besides a variety of editorial voices, journalism also brings us investigative pieces like some of the work of Bellin. About the Register, I hope it recovers some of its past glory, and does not end up as a skeleton in Gannett Newseum.

Karl M Sun 6 Oct 5:54 AM

Opposing Views: How Much?

Points well taken. From my perspective as a news reporter, I always wondered about the long-term effects when newspapers enlarged their editorial sections to include an op-ed page. The original idea was to expand editorial commentary to include outside voices, particularly from those people and groups whose opinions and ideas previously had receive little exposure. What happened, in many cases, is that op-ed pages became receptacles for single and special interest groups. When I covered large corporations, I discovered that many of their PR departments put a great emphasis on production of op-ed pieces that could be used in multiple newspapers. In this way, the original, worthy intent of the op-ed page was being perverted. Today those special interests no longer need editorial or op-ed pages, they have the internet.

Dan Piller Sun 6 Oct 6:55 AM

reply to Dan Piller

I think op-ed pages still serve a purpose. A lot of activists or nonprofits don’t have any other way to get their perspective in front of a large audience. Editorial page editors should prioritize running those commentaries rather than the ones corporations try to place in multiple papers.

Laura Belin Sun 6 Oct 11:22 AM

Poor Des Moines Register and Tribune

I too miss the daily op-ed page in the Register. I switched to online version a couple years ago, but well remember reading the paper version for over 50 years. I subscribe to the CR Gazette, largely to read the sports and “insight” page.

Gerald Ott Sun 6 Oct 1:52 PM

No title

Wonderful article, Herb. Now could someone please explain to me why the register continues to publish Greg Ganske on the OpEd page? I feel like he’s had 12 published pieces in the last year! And the Register highlights his articles in their online edition. What progressive public figure has been published as often?

cbhubbell Wed 9 Oct 5:00 PM