Arnold Garson is a semi-retired journalist and executive who worked for 46 years in the newspaper industry, including almost 20 years at The Des Moines Register. He writes the Substack newsletter Second Thoughts, where this article first appeared.

The story of Iowa’s Arabella Mansfield has been widely mentioned in Iowa newspapers and historical accounts but seldom told.

Mansfield’s name appears every year or so on average in an Iowa newspaper somewhere, usually as a stand-alone sentence or short paragraph within a longer news article about women of achievement in general.

The reference most often includes a single fact: Mansfield was the first woman lawyer in Iowa—and in the United States.

What? The first female attorney in the U.S. happened in Iowa? How did that come about? Who was this woman and what is the rest of her story?

The fascinating answers to these questions require a deeper dig.

Early years

Belle Aurelia Babb was born on her parents’ farm near Burlington, Iowa in 1846, the second child of Miles and Mary Babb.

Two years later, gold was discovered in California, and Miles Babb along with thousands of men from across the country rushed West to become part of the action. He got a job as superintendent of a mining company, then died in 1852 in a mine tunnel cave-in.

However, Miles left provisions in his will for Belle, then 6, and her older brother, Washington, 8, to receive a good education.

Mary and the children moved about 30 miles west to Mount Pleasant, then highly regarded for its educational opportunities. As a reference point, Mount Pleasant, with a population of about 3,500, was somewhat smaller than Burlington but was the eighth largest city in the state and seven times larger than Des Moines in 1850. The largest city in Iowa then was Dubuque at about 13,000.

Mount Pleasant offered a respected high school as well as the highly regarded Iowa Wesleyan University, founded five years before the University of Iowa. Iowa Wesleyan was the first four-year co-educational college in the state and was widely known as the Athens of Iowa. The money Miles left enabled Mary to plan ahead by purchasing scholarships for her children’s future education at Iowa Wesleyan.

Washington enrolled at Iowa Wesleyan in 1860 and Belle followed in 1862. Around the same time, she also changed her name, combining her given name, Belle, and her middle name, Aurelia. The result: Arabella. The Civil War intervened and Washington joined the Union Army. He returned safely to Iowa Wesleyan in time to share the stage in graduation ceremonies with his sister – she, as valedictorian, and he as salutatorian, No. 2 in the class, behind only his sister.

While at Iowa Wesleyan, Arabella met John Mansfield, who would become her husband a few years later. Mansfield, who was two years ahead of Arabella in college, became a professor of chemistry and natural history at Iowa Wesleyan after graduation.

Arabella, meanwhile, also became fascinated with academia, taking a teaching position at Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa, after she graduated. It did not last long, however, with Mansfield possibly a factor in her decision. In a dramatic and pivotal move, she returned to Iowa Wesleyan after about a year. Before long, Arabella, her brother, Washington, and John Mansfield all were studying for the law at a local law firm in Mount Pleasant. Arabella, meanwhile, also pursued a master’s degree at Iowa Wesleyan.

John and Arabella were married in June 1868. A year later, both sat for examination for admission to the Iowa Bar at the Henry County Courthouse in Mount Pleasant.

Francis Springer, presiding judge of the Henry County District Court, conducted the proceedings. The two members of the examining committee were Col. George B. Corkhill and E. A. Vancise, both Mount Pleasant lawyers. Little is known about Vancise except that he was active in the state Republican Party. Corkhill, who wrote the examiners’ report, was clerk of the U. S. Circuit Court for Iowa and a larger-than-life figure. He later moved his law practice to Washington, D.C., where he would become the D.C. district attorney. He made a national name for himself as the prosecuting attorney when the federal government brought Charles J. Guiteau to trial for the assassination of President James A. Garfield in 1881.

Everyone in attendance at the Henry County Courthouse that day in June 1869 understood the importance and significance of what was happening. Women were not supposed to practice law in America. State statutes consistently contained language designed to prohibit it. All of this soon would begin to change.

In Iowa, the state code limited the taking of the bar exam to “any white male person.” Arabella, however, was both intelligent and clever.

She was not only fully prepared for the oral bar exam facing two prominent male attorneys but also was ready with a powerful argument to drop on Judge Springer about why limiting the practice of law to “any white male person” did not exclude women. She accomplished this seemingly impossible twist by citing a line in another part of the state code stating that “words importing the masculine gender only, may be extended to females.”

The line possibly was intended to provide for women as well as men to be included in laws specifying criminal offenses even if the language referenced men only. Oops.

Also, in fairness, accounts of this history differ. The two bar examiners credited Arabella with having “given the very best rebuke possible to the imputation that ladies cannot qualify for the practice of law,” suggesting that she did the research. Other accounts credit Judge Springer for finding the critical line in the state code and choosing to apply it to Arabella’s situation. It also seems reasonable to speculate that the two of them may have collaborated in advance on how to handle the gender issue at the bar exam.

Regardless, Judge Springer’s ruling went to the Iowa Supreme Court, which concluded – likely surprisingly to many observers – that “affirmative declaration that male persons may be admitted is not an implied denial to the right of females.”

Ultimately the words “white male” would be stricken from the code, thus opening the door to people of color as well as to women.

Welcome to the Iowa State Bar, Arabella Mansfield

Well, not exactly.

She was in, all right – the first woman admitted to the bar in the United States of America, almost a century after the country’s founding. But not everyone was welcoming.

Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune carried the flag for those who disapproved of Arabella’s achievement. In a lengthy diatribe entitled “Petticoats at the Bar” that was widely republished, the newspaper basically offered two arguments against the existence of female lawyers.

First, it urged male readers to think of their wife or the maiden of their dreams being engaged all day in “bullying a witness in a crowded courtroom, hectoring the judge, ranting til she is red in the face about the sufferings of the ill-used prisoner at the bar, flattering a stupid jury, visiting the Tombs to consult with their client, the eminent house-breaker or the distinguished pickpocket, discussing in public the foul details of his crime and going home to the domestic fireside cross, weary and hardened with the temper-trying labors of the day. We do not believe any woman could practice a year at the bar without losing almost every quality that makes a woman charming.

Second, the Tribune added: “But besides this, there is still a more serious danger.” It cited a recent occurrence in the British House of Lords as described in a London newspaper:

“The Shedden legitimacy case was resumed this morning for the 15th time before the House of Lords. The Lord Chancellor commented on the extreme prolixity [great word, look it up] of Miss Shedden’s address, which has now occupied 14 days . . .” Continuing, Miss Shedden soon “swooned and was carried out. Dr. Bond being sent for, testified that the lady was suffering from hysteria, brought on by nervous exhaustion.” The case was adjourned and continued to the next day “when, if Miss Shedden should be unable to proceed, her father will be heard.”

The Tribune then provided its own summation and commentary on the case: “When women undertake to argue cases before a jury, how often with the experience of Miss Shedden be repeated? An address 14 days long, and only cut off at last by hysteria! Need we say more?”

A number of newspapers in the U.S. and abroad took a different path, using Arabella’s married surname as a vehicle for commentary on her becoming a member of the bar.

In Wheeling, West Virginia, among other locations Arabella’s entry to the bar was lauded – “Mrs. Arabella Mansfield is one of the brightest ornaments of the Iowa bar. As she took possession of a Mansfield matrimonially, there is no reason why she should not occupy man’s field professionally.”

In Essex, England, and elsewhere, newspapers used the same gimmick with a different twist to lament her achievement — Under a headline, “A Hen-Counsel,” the newspaper noted that Arabella Mansfield and her husband had been admitted to practice law in Iowa. “We have no objection to a lady of the long robe practicing her powers of pleading and cross-examination on her husband, but we think her public exercise of the functions of barrister a decided trespass on Man’s field of labor. Let her confine her wiggings and her gown to her home.”

Two South Carolina newspapers appeared to be mostly going for a laugh in reporting Arabella Mansfield’s admission “to practice at the Iowa bar. Nothing new in this. We have heard of barmaids before,” the newspapers concluded. You can decide for yourself whether it was just a silly play on words – or whether it was intended to be a slam.

Regardless of how the local press in a given place had reacted to Arabella’s story, the whole country and then some had taken notice. The Arabella Mansfield story was reported in scores of newspapers throughout America and abroad, often with the headline, “Beauty of the Iowa Bar.” Despite the national news coverage, however, Arabella’s story did not produce much in terms of immediate change.

Progress for women in law would be slow

Three years after Arabella’s admission to the bar, Iowa’s next-door neighbor, Illinois, rejected the application of Myra Bradwell, founder, publisher, and editor of the Chicago Legal News and widely recognized for her legal knowledge, to join that state’s bar.

The Illinois Supreme Court declined admission to Bradwell because, it said, the state legislature had not intended women to be lawyers. “That God designed the sexes to occupy different spheres of action, and that it belonged to men to make, apply, and execute the laws was regarded as an axiomatic truth,” the court said.

Bradwell appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, where she lost 8-1 in 1873. It took another 17 years before Illinois finally decided that Bradwell was fit to be a lawyer. At this time, in 1890, there still were no more than about 200 women lawyers in America.

The second woman in America to become licensed to practice law was Belva Lockwood, four years after Arabella made it happen in Iowa. Lockwood completed studies in a law program at what is now George Washington University Law School in 1873, but, along with another female student, was denied a diploma. Lockwood appealed to President Ulysses S. Grant, ex-officio chancellor of the university, and received her diploma a week later, in effect making her a member of the bar. She also became the first woman admitted to practice to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1879.

In 1950, only 3 percent of the lawyers in America were women. The number reached 27 percent 50 years later, in 2000. Today, 155 years after the admission of Arabella Mansfield, the number of female lawyers is nearly 40 percent and many law schools have more women than men currently enrolled.

The rest of the story

Arabella Mansfield never practiced law.

It may be that she never intended to. Maybe she simply wanted to break down one of the most symbolic barriers to women’s equality. Maybe she wanted to be at the side of the man who soon became her husband, while both of them studied for the law – and maybe that is how she became Mrs. John Mansfield. Maybe she was trying to satisfy an insatiable love of education – two bachelor’s degrees and a master’s degree in all.

Or, maybe she found something else that seemed to her even more important than breaking down the door to the legal profession.

That would be women’s suffrage, where she turned her full attention soon after being admitted to the bar.

Within a short time, she was elected to serve as Iowa’s delegate to the American Woman Suffrage Association. In 1870, she served as secretary and temporary chair of the first Iowa Women’s Suffrage Convention and became a founder of the Iowa Woman Suffrage Association. She also was president of the Henry County Woman Suffrage Association.

She worked with Susan B. Anthony on suffrage issues.

Arabella had hoped for a woman’s suffrage amendment to the Iowa constitution, but that effort failed in the State Legislature in 1872. The battle for women’s suffrage would take another half century – beyond Arabella’s lifetime. She moved on again.

Arabella and John Mansfield became world travelers. They toured England, France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, Austria, and Scotland, attending classes and studying as they moved through Europe. Among other things, Arabella observed and studied the courts of Europe.

She returned to Iowa Wesleyan in 1873, where she was appointed as a professor of English literature.

In 1879, John Mansfield moved on from Iowa Wesleyan to a small, private college in Greencastle, Indiana, that later would become DePauw University. He became a professor of natural science. Arabella soon joined him there on the faculty.

Five years later, John’s health began to deteriorate. He suffered what was described then as a nervous collapse, possibly what is known today as bipolar disorder. He sought treatment in California.

Arabella took leave from DePauw to earn money for his care and her own support. She lectured around the country. She returned to Mount Pleasant to serve as principal of Mount Pleasant High School. She taught mathematics at Iowa Wesleyan.

Arabella returned to DePauw in the mid-1880s, initially, as preceptress of the Ladies’ Hall in 1886, then registrar, then dean of women. She also served as a professor of history.

After John’s death, she lived on campus in the women’s dormitory and gave Sunday lectures that were well received by students.

In 1893, she attended the Chicago World’s Fair and was recognized by the Congress of Women Lawyers as the first woman lawyer in America. She spoke to a small group of women who wanted to hear her story and became a charter member of the National League of Women Lawyers. This was, perhaps, the only time during her life that she was publicly recognized and honored for her accomplishment in becoming the nation’s first woman lawyer.

In 1894, DePauw was facing a financial crisis as well as a transition in leadership. Faculty salaries were reduced, and programs were reorganized. The dean of the School of Art resigned in 1893, and the dean of the School of Music the following year. Both programs, as well as several others, were struggling financially. The administration used the turnover opportunities to cut expenses.

Arabella was named dean of both the Schools of Music and Art. However, as an expense reduction, she would not receive a salary. Instead, she would receive a portion of the fees paid by students in both schools.

She sustained both programs until ill health forced her to depart from DePauw.

She died of cancer in 1911 at age 65 a few months after moving to the home of her brother in Aurora, Illinois.

DePauw’s Women’s Hall, built in 1885, was renamed in Arabella’s honor. It was destroyed by fire in 1933.

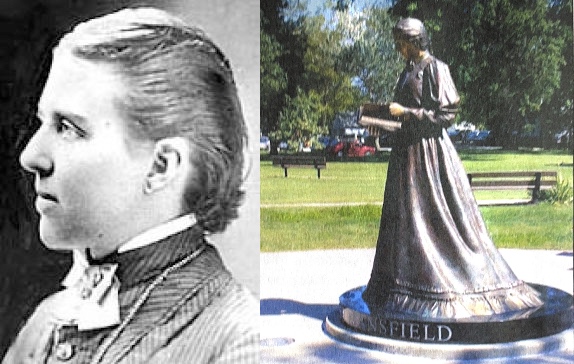

Iowa Wesleyan recognized Arabella with a large bronze statue on its campus in Mount Pleasant in 2008 — although the college closed in 2023.