UPDATE: The Iowa Senate approved the final House version of this bill on March 26, and the governor signed House file 2612 the following day. Original post follows.

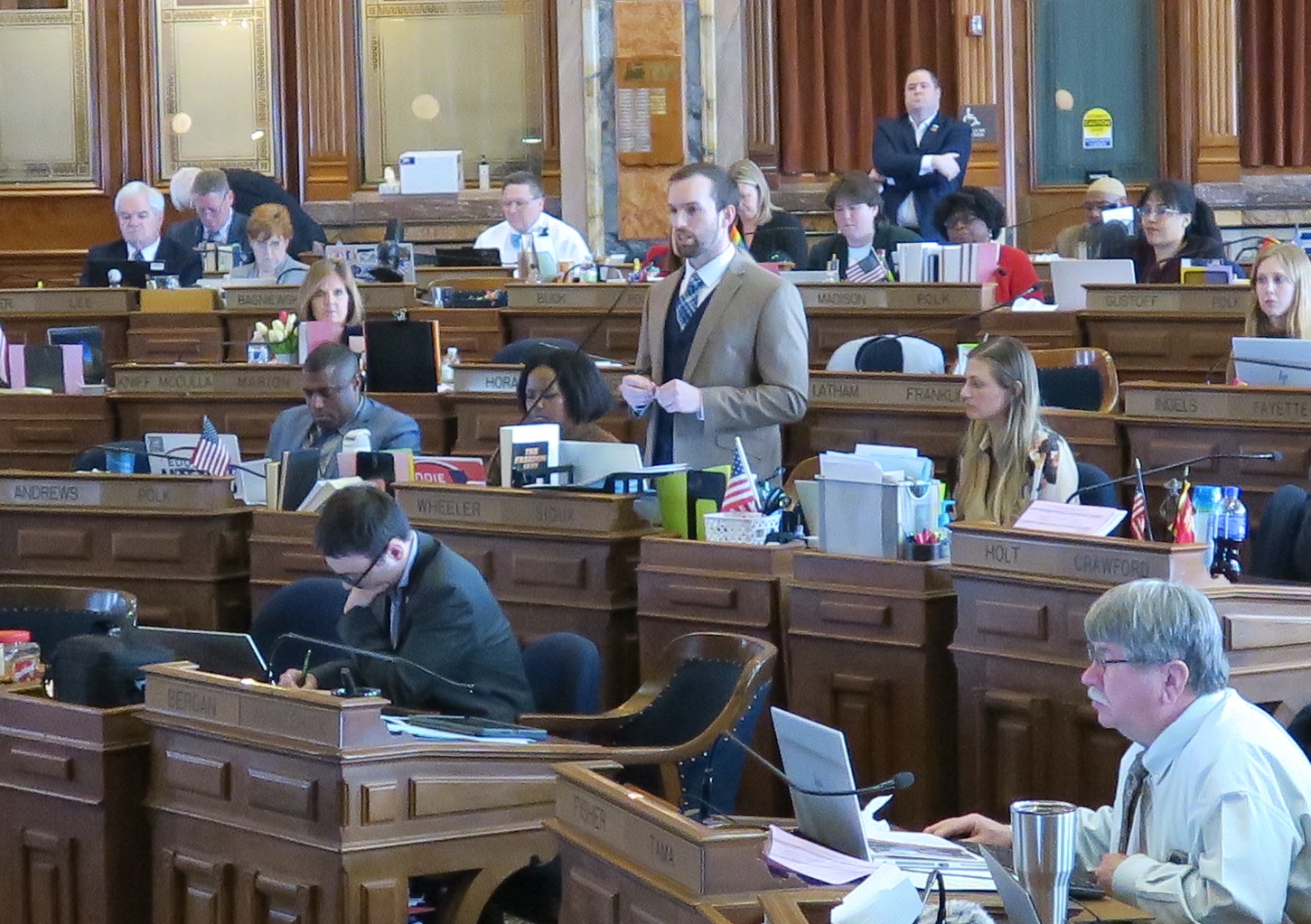

Iowa House leaders attempted to wrap up work last week on the thorniest issue of the 2024 session: overhauling the Area Education Agencies (AEAs) to comply with Governor Kim Reynolds’ demand for “transformational change.” Less than three hours after a 49-page amendment appeared on the legislature’s website on March 21, the majority party cut off debate and approved a new version of House File 2612 by 51 votes to 43.

State Representative Skyler Wheeler hailed many provisions of the revised AEA bill as “wins” for House Republicans during the floor debate. House Speaker Pat Grassley likewise celebrated “big wins in this legislation” in the March 22 edition of his email newsletter.

Nine Republicans—Eddie Andrews, Mark Cisneros, Zach Dieken, Martin Graber, Tom Jeneary, Brian Lohse, Gary Mohr, Ray Sorensen, and Charley Thomson—didn’t buy into the official narrative and voted with Democrats against the bill.

I doubt any of them will regret that choice. If House File 2612 becomes law, it could irreparably harm the AEAs’ ability to provide a full range of services to children, families, educators, and schools.

WHAT HOUSE REPUBLICANS SEE AS “A WIN FOR US”

The House amendment combines provisions on AEAs with language on teacher salaries and K-12 school funding for the coming year. House Republicans had previously sent separate bills on those three subjects to the Senate, but the upper chamber did not act on school funding—which by law should have been enacted by early February—and put less generous teacher pay numbers in its version of the AEA bill, approved March 18.

AEAs and special education

In his opening remarks on the House amendment, Wheeler walked through several provisions that he described as “a win for us.”

Those wins include:

- Creating a new task force (which Wheeler said “every stakeholder wanted”) to study student outcomes and how best to manage and fund various kinds of AEA services;

- Leaving “operational sharing” between school districts and AEAs intact;

- Establishing a new Division of Special Education within the Iowa Department of Education that is “significantly smaller” than Reynolds’ initial proposal. It will have at least thirteen positions in the agency’s Des Moines headquarters and up to five positions in each of the nine AEAs;

- Outlining AEA accreditation standards that incorporate goals for all students, including those with disabilities;

- Capping AEA top administrators’ salaries at 125 percent of the average salary of superintendents in the AEA region;

- Allowing AEAs to continue to provide professional development (if approved by the state Department of Education);

- Permitting school districts to use an AEA from a contiguous region;

- “Ensuring that schools use the AEAs for special education,” which Wheeler described as “the biggest piece of this whole thing.”

The House bill would keep 100 percent of special education funding flowing to the AEAs for fiscal year 2025, which begins on July 1. In year two and beyond, school districts would need to spend 90 percent of special ed funds with the AEA and could use 10 percent of that money to contract with other providers.

As will be discussed below, however, not all services affecting students with disabilities are part of the “special education” bucket. Some fall under media services. The House bill gives districts control over 60 percent of funds for media or education services in FY 2025, while only 40 percent of that money would need to be spent with the AEA. Beginning in July 2025, school districts could redirect 100 percent of media and education services funding away from AEAs.

The latest House bill certainly preserves a greater role for the AEAs in special education than Reynolds’ initial plan, which would have directed all special ed funding to school districts and allowed them to contract with any provider. It’s also an improvement on the Senate GOP bill, which would have required districts to spend only 10 percent of their special ed funds with the AEA in year two and beyond.

Teacher pay

Like the plan Reynolds outlined in her Condition of the State address, the latest version of House File 2612 would increase minimum salaries for both new teachers ($47,500 next year and $50,000 in year two and beyond) and those with at least twelve years of experience ($60,000 next year and $62,000 in subsequent years).

Wheeler also highlighted teacher pay provisions that include $14 million to increase salaries for support staff, sometimes known as para-educators or paraprofessionals. Neither Reynolds nor Senate Republicans sought to raise pay for those education workers. Grassley wrote in his email bulletin, “The Iowa House fought hard” to increase wages for “our paraprofessionals who do such important, difficult work.”

During the debate, Republican State Representative Chad Ingels called the teacher compensation language “maybe the most valuable part of this bill for rural Iowa students.” He cited the “tremendous difficulty” small school districts face in recruiting and retaining teachers. “It’s been an actual crisis. And it leads right to special education delivery,” because often teachers without special education training are assigned to special ed classrooms “under transitional or temporary licenses.”

Ingels became emotional when talking about para-educators. “While AEA personnel are extremely valuable, para-educators are there every day beside my kids. And they’re underpaid.” They could make more money working at Casey’s or Wal-Mart.

Ingels has two children with Down syndrome, who were born 12 years apart. He said his older daughter had the same para from K-12. “She did fabulous.” In contrast, his son, who is currently in 8th grade, has had ten different paras. “Those people all care, they’re helpful. But there’s no continuity. And that makes a difference.”

House Democrats unanimously supported the earlier teacher pay bill, which set a minimum $15/hour salary for para-educators. During the March 21 debate, several Democrats criticized the House File 2612 amendment for not requiring districts to pay paraprofessionals at least $15 per hour. When State Representative Ross Wilburn asked why the new amendment didn’t include a minimum hourly wage, Wheeler explained, “It’s very difficult to get good data on this,” and “we just don’t have good enough data on it.”

Wilburn noted the lack of data illustrates why Democrats and many stakeholders have been saying a task force should thoroughly study these issues before lawmakers impose major policy changes on the AEAs.

Since Iowa’s governor can item veto portions of appropriations bills, I asked Grassley following the debate if he was confident Reynolds would not veto any part of House File 2612.

He replied that he can’t speak for the governor, but said her office and Senate leaders are “well aware of how important” that $14 million appropriation is to House Republicans.

A written statement from Reynolds, issued minutes after the House approved the revised AEA bill, welcomed the vote “to further strengthen Iowa’s education system in meaningful ways.” The governor praised “Raising minimum salaries for new and experienced teachers” but did not mention the benefits of increasing pay for support staff.

Senate Majority Leader Jack Whitver struck a positive tone in his own March 21 news release: “I am happy to see progress on AEA reform, raising starting teacher pay, and education funding. Senate Republicans will discuss the new version of the bill next week and I am looking forward to a resolution on these issues.” That’s not a firm promise to send the latest House bill to the governor’s desk.

Public school funding

In an apparent nod to Reynolds, the new House bill would increase “supplemental state aid” (per pupil funding for K-12 public schools) by 2.5 percent, the level the governor wanted. Grassley acknowledged in his newsletter that his caucus would have preferred a 3 percent increase, the amount House Republicans voted for in February. At that time, Democrats unsuccessfully advocated for a 6 percent increase in state aid to K-12 schools, noting that state funding has lagged below the rate of inflation for at least a decade.

Republicans maintain that if you combine the 2.5 percent increase in per pupil funding with the $96 million going to districts to support higher minimum teacher salaries, $14 million for para-educators, and $10 million the legislature plans to allocate for “school safety” policies, it adds up to the equivalent of a 5 percent increase in supplemental state aid.

Yet several large school districts have already announced plans to cut staff in anticipation of state funding shortfalls for the coming academic year, House Minority Leader Jennifer Konfrst pointed out during the AEA bill debate. Democratic State Representative Adam Zabner warned colleagues “about one thing that this bill means for sure. This bill means the closure of Hills Elementary School.” Located in a small town, it’s the smallest school in the Iowa City school district, and the superintendent has recommended shuttering the facility to save money.

A straight 5 percent increase in state funding per pupil would give school districts more flexibility to address their own pressing needs.

GOP INSISTS “NOTHING IN HERE” HURTS SPECIAL EDUCATION

Many Democrats have remarked on the enormous number of Iowans who have contacted lawmakers this year, begging them not to blow up the AEA system. It’s a deeply personal issue for many families.

Advocates of House File 2612 have pushed back against any suggestion their proposal could harm special education or the AEAs. Wheeler slammed what he called “inflammatory” and “false” comments about the threat to disabled kids. He has a five-year-old autistic child, and he and his wife “have seen incredible growth in our daughter” thanks to AEA services. He said he would never push for any legislation that would harm the disability community.

Ingels decried what he called “fear mongering” that was “over the top. We are not dismantling the AEA system.” He noted that his own children “have benefited greatly because of the people that work at the AEA.”

Wheeler insisted in his closing remarks, “There is absolutely nothing in here that hurts special education.”

Grassley told journalists soon after the floor debate that maintaining “certainty for special ed services” was House Republicans’ “number one priority, and we held the line on that, and we were obviously successful.” The next day, he echoed the point in his newsletter: “Because this bill requires school districts to use the AEAs for special education services, there will not be any disruption to special education services.”

If only that were the case.

“THE PROPOSED CHANGES ARE ABOUT MONEY AND POWER”

Wheeler asserted in his opening remarks, “We don’t have any money coming out of the system.” He may have forgotten that under the revised House File 2612, school districts would have the option to spend 10 percent of their special ed funding with providers outside the AEA, beginning in July 2025.

Even worse for the AEAs, school districts would receive 60 percent of media and education services funding for this coming year, while just 40 percent would be guaranteed to flow to the AEAs. Beginning in July 2025, districts would receive 100 percent of funds for media and education services.

State Representative Sharon Steckman, the ranking Democrat on the House Education Committee, directed colleagues to read page 30, line 32 of the House amendment. It allows school districts to use media and education services funds “not required to be paid” to an AEA “for any school district general fund purpose.”

Wheeler characterized that approach as giving schools more “local control.” He denied it would lead to “massive losses” and called for trusting schools and superintendents, who know their own students’ needs “better than anybody.”

Steckman pointed out, “Media services deliver a lot of the special ed services to our families. So if AEAs have no idea what money they’re going to have coming in, how are they going to afford to buy those services?”

With state funding per pupil set to increase by just 2.5 percent, Steckman added, “if I were a superintendent, I’d give my staff a raise. I wouldn’t spend it with the AEAs, I’d use it to give my staff a raise, because I’m woefully underfunded by us.”

Ted Stilwill, a former director of the Iowa Department of Education and outspoken critic of plans to restructure the AEAs, told Bleeding Heartland via email,

While there may well be changes to the AEA system that could improve outcomes for Special Education students, none of the proposed changes provide any strategies providing any evidence of improving outcomes. The proposed changes are about money and power and have little to do with kids. Some districts will have more money, many will have fewer services. All districts will be more on their own for staff development and technology support and the money that provided to support those vital services will be sacrificed to maintain decent class sizes when times get tough—as they always do.

Several Democratic lawmakers warned about the potential impact on students.

“THE MOST VULNERABLE KIDS WE HAVE IN IOWA”

State Representative Molly Buck, who is a classroom teacher, said she worries about kids who need assistive technology devices to communicate. Those devices are currently delivered through vans funded from the AEAs’ media services bucket. “When those vans stop running, I worry about how they’re going to get their technology devices.”

“We are rushing through legislation that affects the most vulnerable kids we have in Iowa,” Buck continued. “Our most vulnerable population, the ones that can’t speak for themselves, the ones that can’t defend themselves.”

A speech pathologist in the Quad Cities wrote to State Representative Ken Croken about how the AEA bill could affect her work. He read her message aloud:

This person recently met with the assistive technology team from the Mississippi Bend AEA to problem solve for a non-verbal student. The team suggested three different communication options.

Assistive technology is crucial for some children with disabilities. If the AEAs lose much of their dedicated funding for media services, who will support speech pathologists, teachers, and para-educators to help students with communications? How will communication devices be maintained and kept up to date? How will old generation iPads get replaced?

Croken’s constituent also explained, “Many education classrooms and speech therapists use core word boards.” A picture is provided, and the AEA print shop (another part of media services) prepares the posters in color. “How will we get poster boards without these printing services? I need these boards in color, because the color indicates the type of word.”

Without the van services now provided through the AEA, “How will I obtain the materials that the assistive technology team recommended to me?” Will she need to waste time driving to and from the AEA office? “If I miss 40 minutes, I will not see six students for speech therapy that day.” It’s “almost impossible” for this person to pick up materials after school, because she often has IEP meetings during that time.

IMPACT ON OTHER AEA SERVICES

Several House Democrats spoke about other services that may suffer if AEAs lose part of their funding, such as professional development, crisis intervention, English language learning, science materials, and gifted and talented development.

Buck said that when she read through the new GOP amendment, “I didn’t find anything about challenging behavior teams or autism support teams, that show up and support teachers when a new student, or a new diagnosis is given to a student in your classroom.”

State Representative Tracy Ehlert said she “didn’t have adequate time to really dig into” the 49-page amendment before debate. “But at my first glance, it still doesn’t tell me what really happens with those birth to 5 services,” which so many families rely on when they have concerns about their child’s development. Her own family used those services.

Ehlert is an early childhood educator with extensive experience in child care. She mentioned that AEAs now offer response teams to help child care providers manage difficult behaviors. The team can “give them ways to work with that child, so that young child’s not at risk of being suspended or expelled from that child care program.” That would be stressful not only for the child, but also for the family that needs to find new care while much of Iowa is a child care desert.

State Representative Mary Madison read from another Iowan’s message. That person’s teenage daughter has an IEP “to address significant mental health needs,” including anxiety and depression. She was hospitalized with suicidal ideation in eighth grade, “and the only services immediately available upon her discharge were that of the AEA.”

The Iowan talked about the various special services the AEAs now provide, such as school psychologists, school social workers, special education partnership coordinator, gifted and talented programs, mental health consultants, and school counselors consultants.

Madison concluded, “You are taking a quality system and turning it into mediocre.”

Grassley wrote in his weekly newsletter, “This bill does not terminate any employees of the AEA’s” and “does not prohibit the AEAs ability to perform any of the services they do now.” But once AEAs lose guaranteed funding streams, it will be hard to avoid staff and program cuts.

“THAT’S HOW IT WORKS HERE”

This year’s entire AEA misadventure has been an object lesson in how not to make policy: from the cherry-picked data and flawed analysis used to justify the governor’s plan, to the exclusion of key stakeholders from discussions, to false claims about an impending federal takeover of special education.

The procedural tricks used to pass the AEA bill before House members went home for the weekend reached a new low.

Normally, amendments are published at least a day before Iowa House floor debate. Normally, members can speak for up to ten minutes on a bill, and a vote on final passage doesn’t happen until everyone who wants to weigh in has had a chance to speak.

On March 21, House Democrats received a draft version of the 49-page amendment at about 1:25 pm, Konfrst said. The public wasn’t able to start reading the text until the amendment appeared on the legislative website around 3:55 pm.

After hours in recess, the House resumed session at 3:53 pm. Republicans requested a quorum call and quickly passed a “time certain” motion cutting off debate on House File 2612 at 6:30 pm.

Time certain motions used to be extremely rare in the Iowa legislature. Years would pass without the majority party using the tactic. Since the GOP gained a trifecta in 2017, it’s happened almost every year in the House—sometimes more than once—to limit debate on controversial bills.

This was a particularly outrageous maneuver. AEAs are a topic of massive public interest, directly affecting tens of thousands of people. Iowans had at most two and a half hours to review an amendment with lots of moving pieces before the House voted on it. The chamber ended up debating the bill for less than two hours.

Grassley and other Republicans have denied springing new language on anyone. From the House speaker’s newsletter:

I know the Democrats are trying to say that the process was rushed because of the timeline of debate yesterday. Let me assure you – we have discussed these policies extensively with Iowans, educators, and as a caucus. There wasn’t anything in the final amendment that hadn’t been debated previously in the Legislature. We took a lot of feedback from Iowans in our crafting of this final package. We heard from parents, teachers, superintendents, the AEAs, the Department of Education and more.

Nice try, but not convincing. No one outside the House GOP caucus knew exactly what mix of policies would be in the amendment. Even subject matter experts need some time to read through a bill and understand the intended or unintended consequences.

A time certain motion might be justified in extremely rare circumstances: say, in order to finish work on the budget on the last day of the fiscal year. Or if the minority party was dragging out debate for days on a bill that had been in the public domain for some time.

There was no need to bring House File 2612 to the floor on Thursday. No legislative deadline loomed. The Senate had gone home already, so wouldn’t be able to take up the bill until the following week anyway. House members could have come back to debate the revised AEA bill on Monday.

Unless leadership worried that Iowans would talk legislators out of supporting the bill over the weekend. Remember, they only managed to put 51 votes on the board.

If House leaders felt they needed to pass the bill on March 21, why end debate at 6:30 pm? To all appearances, it was to let members watch the Iowa State men’s basketball team play in the NCAA tournament, starting at 6:35 pm. In addition, the time certain allowed GOP State Representatives Brent Siegrist and David Young to vote for the AEA bill, then drive to Omaha in time to watch the Drake men’s basketball game in person, shortly after 9:00 pm.

During the debate, Croken said out loud what many were thinking: “Why are we doing this? And more importantly, where’s the fire? I really don’t want our deliberations limited by the timing of a basketball game […].”

After the vote, I asked Grassley whether debate was cut off so people could watch the NCAA games. His response was a classic non-denial: “I haven’t watched one basketball game. I don’t even know who’s playing and when. And if I did I wouldn’t pick the games right anyways.” (About an hour earlier, he or his staff had just posted on the speaker’s Facebook page, “Good luck to all of the Iowa teams playing in March Madness!”)

Grassley went on: “That was done for the reason being that, again, we wanted to make sure that we achieved this goal by getting home. It was a number that had been batted around, several different numbers, and that’s where we landed.”

The answer insults everyone’s intelligence.

During his floor remarks, Ingels admitted the minority party hadn’t had a lot of input on this bill. “And that’s how this works here.” But he defended the hard work of House Republicans, who spent “close to fifteen hours sitting downstairs, hashing this over.” He said “that amount of discussion on any bill, or any topic, does not happen here. And Iowa needs to know that.”

With all respect, Iowans needed time to absorb the AEA “compromise” and reach out to their representatives about any concerns.

While speaking against House File 2612, State Representative Heather Matson told colleagues she was “devastated”: “What was built and strengthened over half a century could be torn apart in a matter of months for no good reason.”

Konfrst had little patience for Wheeler’s recitation of House “wins” in the bill: “It’s not a game. […] Don’t call this a game. Don’t talk about wins. Kids lose.”

6 Comments

Any chance senators will slow this train?

Is there now any realistic chance of slowing the process and opening the AEA topic for more study? The Republican trifecta seems determined to fix what’s not broken. Where’s the fire, indeed!

Iowapeacechief Sun 24 Mar 10:02 AM

Heritage & Co. have long been pushing to

end special-ed requirements, they like to run elections against teacher unions but they know that much of the increases in ed budgets over the 20C have to do with extending public school services to more kids and they of course want to cut all taxes. Part of the move to send public money to religious schools is an end run around human/civil rights protections for kids while undermining school worker power.

dirkiniowacity Sun 24 Mar 11:22 AM

reply to Iowapeacechief

I think there is a very realistic chance the Iowa Senate won’t take the House amendment. But the governor is determined to do something to blow up the AEAs, and it appears K-12 school funding is being held hostage to that.

Laura Belin Sun 24 Mar 12:30 PM

Maybe the House version is good

The House proposes that school districts keep almost all their allocation to AEAs (90%) and decide what to do with the remaining 10%. This is hardly a major change. And the bill comes with perks like higher salaries for teachers.

The journalist might be rightly outraged that deliberations were cut short by House members having family plans for the night, but all things considered, the House proposal is better than the Senate’s, and possibly an improvement over the state of the art.

Karl M Mon 25 Mar 8:19 AM

as I wrote

“The latest House bill certainly preserves a greater role for the AEAs in special education than Reynolds’ initial plan, which would have directed all special ed funding to school districts and allowed them to contract with any provider. It’s also an improvement on the Senate GOP bill, which would have required districts to spend only 10 percent of their special ed funds with the AEA in year two and beyond.”

That doesn’t mean it’s a good bill or an improvement on the current AEA structure. The post explains the many problems this could create for certain kinds of AEA services, including some affecting special education.

Laura Belin Mon 25 Mar 11:22 AM

Not a win for most of Iowa's children and youth in public schools

The allocation of 136 million in taxpayer dollars to subsidize students attending private schools while spending less than $200 more on per-pupil state aid raises concerns about equity and priorities in education. This decision to pay $7,636 per student disproportionately benefits 17,000 students attending private schools at the expense of those in public schools, including the 63,363 children and youth with disabilities in Iowa’s public schools. This allocation of funds prioritizes private education over the needs of the great majority of Iowa students who attend public schools, especially in rural areas, including those who require special education services.

iowaralph Mon 8 Apr 3:06 PM