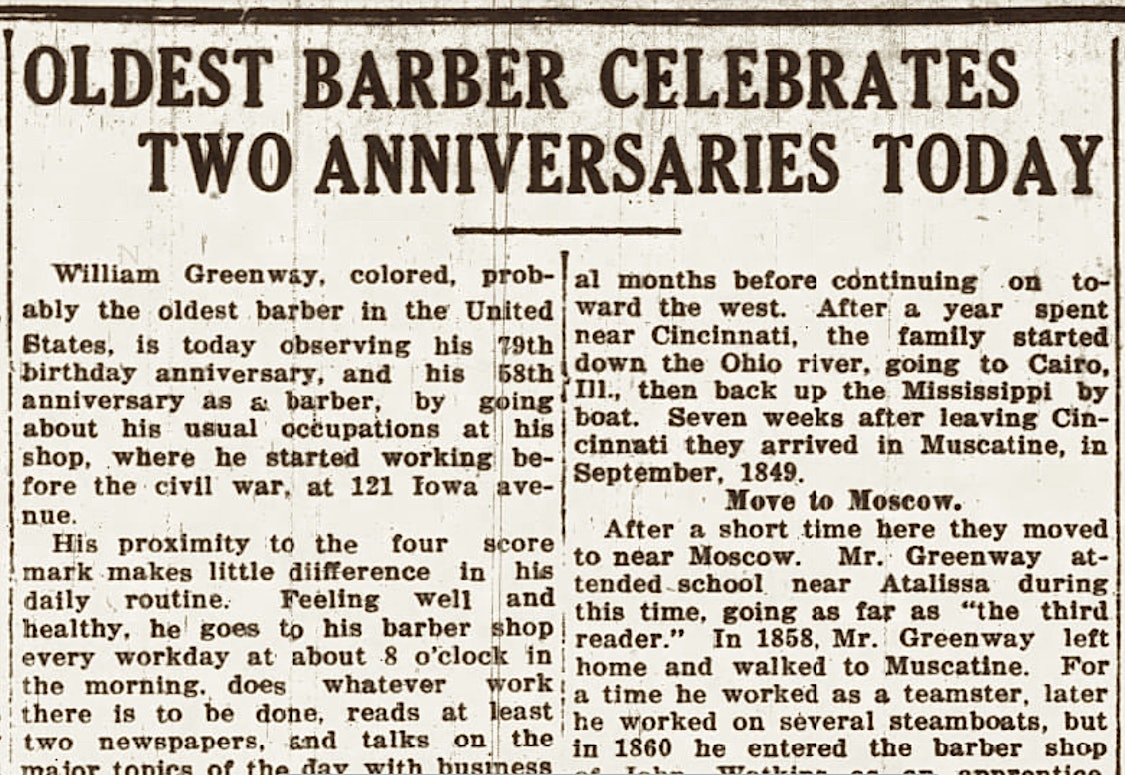

This column by Daniel G. Clark first appeared in the Muscatine Journal on August 23, 2023. Above: Muscatine Journal and News-Tribune, September 23, 1919.

Recently I told John Jelly’s 40-years-later account of a “colored man” bringing food for a “freedom seeker” hidden on a farm in northern Muscatine County in 1855. From not much evidence, I concluded that man must have been William H. Greenway (1840-1930).

Then I discovered Jelly had exposed young Greenway a decade prior to his 1896 letter to historian Wilbur Siebert. That version of the little-known story identifies Jelly as Atalissa correspondent.

Muscatine Weekly Journal, February 5, 1886: “Taking a short cut across the field from one house to another, I came across a spot of ground which will ever be memorable to some of the old settlers, the land then being owned by Dr. A.M. Vanpelt, who would rather have been engaged in hiding runaway slaves than eating Rambo apples or drinking sweet cider. It was here in the middle of a cornfield where Tom, a runaway from Missouri, was quartered for six weeks with a hogshead for a shelter, while his master was all over the country looking for him and stopped at the house and enquired if they had seen the boy and put an advertisement on the gate post offering a reward of $500 for his capture and return. There is probably no one living now in Iowa who knows anything of the circumstances, unless it be Uncle Billy Greenway, the popular barber on the Avenue, Muscatine. He was then a boy and lived with his parents in a house on the farm (long since pulled down.) It was he who was entrusted with the important task of taking Tom his daily rations and keeping him posted as to the whereabouts of his master and when it would be safe for him to proceed on his way to Canada, and now I suppose Billy could tell all about how Tom got as far as Davenport in the night (this was just before the railroad was built) and how he crossed the river between sacks on a wagon and how he got transportation from Rock Island through to Canada and of the letter telling that Tom had arrived safe in Canada and at last he was free and a man.”

Those “circumstances” were indeed a well-kept secret. Yet, as I reported, Jelly’s 1896 letter names various people who might have played some part in the dangerous enterprise. Siebert’s transcription, if not Jelly’s handwriting, mispelled Greenway as Greening, a slip that hid the story until the magic of online searching.

Uncle Billy? The nickname appears again in a eulogy by Frank Richman.

Muscatine Journal, September 1, 1930: “He lived a long and useful life, and, as I would judge it, a happy one. I feel honored in testifying before those who have not known him and of him for many years of his life, as I have known him. … Possibly no man lives out his life without creating some enemies. If William Greenway, the deceased, ever had any, I never heard of it, and if there ever were any, I believe their enmity to have been without cause. It is in no spirit of irreverence, but rather to emphasize a thought, I would say that if St. Peter keeps his books aright, as I assume he does, there are no entries in red ink on the debit side of Billy Greenway’s account. His friends addressed and spoke of him as ‘Billy’—the nick-name was not used in the sense of an undue familiarity. It was uttered rather as an expression of and in harmony with a personal affection for him by the speaker.”

A brave tribute from the president of the county bar association, described at his own death in 1934 as “dean of Muscatine attorneys.” An intentional kindness when Greenway’s sons were in the news for repeated allegations of violating Prohibition liquor laws and various financial troubles.

Words of a true ally, from a time when news items routinely identified persons as “colored” or “negro”—as if to make a point.

E.F. “Frank” Richman’s father was J.S. Richman, who was the defense attorney for freedom seeker Jim White in 1848 and in 1867 the district court judge who ruled against the Muscatine school board in the Susan Clark case—the desegregation precedent upheld by the Iowa Supreme Court.

So many dots to connect! I’m wanting to learn more about the Van Pelts and locate their farm site, if not Jelly’s memorable “spot of ground” where a man on the run found shelter in and around a barrel in a cornfield.

The Muscatine County site deserves listing in the Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, a program administered by the National Park Service.

The inaugural Iowa Underground Railroad Ride, September 15-17, features a southwestern route. Let’s hope it’s headed our way some year soon. Learn more at https://www.iowaundergroundrailroadride.com.

Next time: Alexander Clark’s initiation to the bar