Scott Syroka is a former Johnston city council member.

Democrats have a major opportunity to increase their appeal in rural America, thanks to the policy framework crafted by President Biden, which he laid out in his June 28 address on Bidenomics in Chicago, Illinois.

While Democrats have successfully embraced Bidenomics to pass legislation like the American Rescue Plan, Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, CHIPS Act, Inflation Reduction Act, and beyond, they haven’t done enough to champion Bidenomics through a rural-specific lens.

By using this framework to present a vision for an inclusive rural economy, rather than the trickle-down status quo of exploitation, Democrats can draw a clear contrast with their Republican opponents.

If they choose to seize this opportunity, Democrats can begin to stop the electoral bloodbath in rural areas, shrink the margins, and maybe even start to win again.

The forgotten history of America’s family farm movement and its fight for parity shows us how.

A RURAL ECONOMY THAT KILLS

Twenty-three years ago, 60 Minutes aired an excerpt from a suicide note that an Iowa farmer left for his wife and kids: “All I ever wanted was to farm since I was a little kid, and especially this place. I know now that it’s never going to happen. … I’m just a failure at everything it seems like.”

This year, New York Times journalist Elizabeth Williamson published an article with an eerily similar excerpt from a Wisconsin farmer’s suicide note: “I want my old life back, but I can’t get it anymore. Every thing I do fails.”

These farmers blamed themselves for their “failure”—even though that happened by design.

In the second half of the twentieth century, corporations lobbied Congress to transform agriculture from the once-successful parity system that farmers could raise a family on, to the failed dis-parity system that drives some farmers to kill themselves.

By taking up the fight for parity again as part of the Bidenomics framework, Democrats can make inroads in rural America.

Jesse Jackson speaks in Columbia, Missouri during his 1984 presidential campaign. “I looked out there, all these guys in hoods. Sort of a little moment there,” Jackson recalled. According to Slate, Jackson later realized that farmers arrived wearing paper bags over their heads to obscure their faces from farm bureau officials. The man in the blue jacket wears a button that reads “PARITY, NOT CHARITY”. Photo by Robert R. McElroy, available via Getty Images.

UNDERSTANDING PARITY

To understand how parity works, imagine a farmer, Sara, operated a farm after Congress and President Franklin D. Roosevelt first established the parity framework in 1933.

America had signed a new social contract with farmers like Sara under parity. In addition to risks farmers disproportionately shouldered, like natural disasters and war, we also acknowledged the inherent lack of price responsiveness in agriculture.

When there’s oversupply of crops and crop prices are low, we don’t start eating five meals a day instead of three.

When there’s undersupply of crops and crop prices are high, farmers can’t immediately produce more. Planting decisions are made far in advance, and farmers face constraints like the natural plant lifecycle.

This is a key difference between farming and other industries where you can hire or fire workers, expand or reduce hours, or open and close stores and factories to help manage supply.

We the people—through elected representatives and the U.S. Department of Agriculture—acknowledged these factors posed unique challenges. So we agreed to provide farmers like Sara the equivalent of a living wage.

In exchange, Americans received a safe, resilient food supply that helped protect our national security, strengthened the labor market, and stewarded our natural resources.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt (left) and Vice President Henry A. Wallace (right) in front of radio microphones in the early 1940s. Under their leadership, America created the parity system that led to rural prosperity across the country. Photo available via Henry A. Wallace Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of Iowa Libraries.

HOW PARITY WORKED

Family farm movement leaders like Cornelius Blanding, George and Patti Naylor, and Brad Wilson have explained how four key components together created parity.

First, we grew the middle class and established what was effectively a minimum wage for farmers. By instituting price floors that guaranteed a minimum price for Sara’s crops, America said, “We won’t let crop prices fall below what it costs you to actually produce those crops.” We told farmers like Sara she wasn’t on her own, and we promised to do our part by buying and storing any crops she produced beyond what the market would absorb. This predictability ensured that Sara could securely invest in the seed, farm machinery, and other inputs ahead of realizing a post-harvest profit.

Second, we prevented crop overproduction using targeted investments in inventory management infrastructure. Once you guarantee a minimum price, there’s an incentive for Sara to produce more than what’s needed. To counteract oversupply, the Secretary of Agriculture projected the crops needed to meet the country’s needs each year. Then, farmers like Sara worked with USDA to determine how much to produce, with oversight provided by local, democratically elected committees. This inventory management served as a countervailing force to price floors.

Third, we protected Americans from crop underproduction using price caps. Once you manage crop inventory, you increase the risk that farmers like Sara may underproduce due to unforeseen circumstances like war or natural disasters. By agreeing to price caps for crops, farmers said to America, “In exchange for guaranteeing us a price floor with the stability it provides, we consent to price caps with the stability for you that provides.” These price caps functioned in a similar spirit to how Bidenomics capped insulin and prescription drug prices for seniors on Medicare, preventing excessive price spikes.

Fourth, we built a resilient farm supply chain that protected American interests with strategic emergency crop reserves. If crop prices hit their price cap, it functioned as a trigger to release these reserves onto the market that America had previously bought from farmers like Sara and held in storage.

The release of reserves helped keep farm prices within the parity band between the price floor and the price cap. We see echoes of this resiliency model with how President Biden has used the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to help smooth oil prices.

A man holds a sign advocating for fair prices for Black farmers. According to NESAWG, Black farmland ownership plummeted as Congress dismantled parity, from a peak of 15 million acres in the early twentieth century to just 2.3 million acres by 1997. While the decline in the number of overall farmers was shocking, the decline among Black farmers was even worse, dropping from 218,000 to just 18,000. Photo by Farm Aid.

PARITY BRINGS PROSPERITY

Parity is like a four-legged chair. Without all the legs, the chair collapses. Prior to its existence, Americans suffered from repeated market failures in agriculture, just as they do today without parity.

However, during the parity years, rural and urban Americans alike saw increasing, shared prosperity as it boosted Americans’ fortunes in a fiscally responsible way while often generating a profit for taxpayers.

Accordingly, the success of shifting farm policy factored into FDR’s decision to elevate his secretary of agriculture to the vice presidency. That secretary was an Iowa Republican-turned-Democrat, Henry A. Wallace, who was born in Orient, Iowa before starting a farm in Johnston, beginning in 1914.

Henry A. Wallace (right), U.S. Secretary of Agriculture at the time, walks through a Johnston, Iowa corn field with corn breeder Raymond Baker (left) in 1935. As Secretary of Agriculture and eventually Vice President, Henry A. Wallace was a major champion of parity. Photo available via Henry A. Wallace Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of Iowa Libraries.

CORPORATE AMERICA FIGHTS BACK

However, not everyone liked parity. While ordinary Americans benefited from more money in their pockets, corporations viewed it as an enemy to be vanquished, the intricate history of which has been recounted by journalists like Luke Goldstein in The American Prospect.

In 1962, corporate executives from companies like Ford, Merck, and Sears published a report advocating for an end to parity to solve “the farm problem.”

They argued doing so would “induce excess resources (people primarily) to move rapidly out of agriculture.” Alongside the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, these executives successfully lobbied Congress to dismantle the parity system piece by piece over decades.

Similar in effect to lobbying for the end of a minimum wage for workers, corporations lobbied for the end of price floors for farmers. Since parity’s price floors were indexed to production costs, reducing and then eliminating them meant farmers struggled to survive.

By putting farmers out of work, corporate America could lower its costs by increasing its supply of workers. This forced migration of previously rural and rural-adjacent residents into cities helps explain the collapse of the rural economy.

By 1996, Congress destroyed the last vestiges of parity and passed a Farm Bill that eliminated already-reduced price floors for nearly all crops, in addition to ending most of what was left of public supply management programs.

The strength of family farms previously acted as a counterbalance to corporate power for workers. Even if you worked in a city, your negotiating power with your employer was strengthened by a strong farm economy. The absence of this counterbalance contributes to the general sense of precariousness that Americans feel today.

Democrats used to have a better understanding of this. Jamelle Bouie reported in Slate that former presidential candidate Jesse Jackson said, “[Rural Whites and urban Blacks] have always had more in common than other folks supposed… We’ve both felt locked out. Exploited and discarded.”

Jackson continued, “People saying about the family farmer exactly what they say about unemployed urban Blacks, ‘Something’s wrong with them. If they worked hard like me, wouldn’t be in all that trouble.’ Fact, more you get into this thing, more you realize that Black comes in many shades. We’ve found out we kin.”

General Motors workers hold picket signs outside of the Corvette Assembly Plant in Bowling Green, KY on September 16, 2019. At the height of the family farm movement in the twentieth century, farmers understood supporting labor’s fight for fair wages benefited farmers, just as labor understood supporting farmers’ fight for fair wages via parity benefited labor. Photo by Brian Walker, available via Shutterstock.

THE END OF PARITY LEADS TO A TRICKLE-DOWN ECONOMY

In addition to weakening labor, destroying parity also enabled corporate monopolies like ADM, Cargill, and Tyson to buy more and more grain for less than it cost farmers to produce. Since these corporations rely on large amounts of grain to operate, this amounted to farmers subsidizing the cost of some of their largest expenses.

Now, we’ve seen decades of a massive (and continuing) wealth transfer from farmers and Main Street to corporations and Wall Street. The Cargills alone have more billionaires than any other family in the world–fourteen as of 2015.

As more and more small farms have failed, the effects have spread through rural towns and mid-sized cities alike. According to PBS, rural America lost one business for every four farms that failed during the 1980s. The Quad Cities in eastern Iowa and western Illinois alone lost tens of thousands of manufacturing jobs as fewer farmers meant less demand for farm machinery and agricultural supplies.

Under today’s disparity agriculture system, Congress structures our farm economy as a trickle-down, corporate welfare program at the expense of ordinary Americans.

This has changed the economics of farming. Farmers became incentivized to get big or get out, plant fencerow to fencerow, and use more fertilizer and pesticides, which corporations have been happy to sell them.

Factory farming methods like concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, skyrocketed as corporations could now pay farmers below the cost of production for grain—like a form of wage theft—while family farming methods like sustainably raising livestock on pasture became less profitable.

Ted Cruz speaks at The Columbia Armory in South Carolina during his 2016 presidential campaign. Cruz is one of multiple Republicans to receive campaign donations from Pauline MacMillan Keinath. Keinath is believed to be the largest individual shareholder in Cargill and the richest person in Missouri. Keinath’s great-grandfather, W.W. Cargill, founded the company in 1865 in Conover, Iowa, which is known as a ghost town today. In addition to Cruz, Keinath has donated large sums to politicians like Todd Akin, Josh Hawley, Steve King, as well as organizations like Black Americans to Re-Elect the President (2020) and the Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life Candidate Fund. Photo by Crush Rush, available via Shutterstock.

THE RISE OF CHICKENIZATION

In his book, The Meat Racket, Christopher Leonard calls the rise of this new factory farm-friendly model of raising animals “chickenization.”

Aided by the end of parity, corporations like Tyson pioneered chickenization in the chicken industry. They have since imposed it on nearly every other sector of the farm economy.

To better understand how it works, imagine a farmer, Jorge, wants to raise chickens. Due to market consolidation he’s essentially forced to sell them to one of the Big Four chicken companies that form a monopoly: JBS (Pilgrim’s Pride), Perdue, Sanderson Farms (now Wayne-Sanderson after yet another industry merger in 2022), and Tyson.

Let’s assume that Tyson is the only buyer in Jorge’s area, which isn’t an outlandish assumption. Corporate monopolies such as Tyson have allegedly engaged in a variety of schemes to lower the amount farmers earn, including tactics like ceding control of certain regions of the country to each other to lessen competition.

In fact, these corporate monopolies are so effective at driving down incomes that after adjusting for inflation, the average chicken farmer earned less in 2020 than they did in 1990.

Leonard explains in his book that these effects ripple out beyond farmers themselves. In counties where Tyson operates, he found residents were “worse off in terms of income growth than their neighbors, even as Tyson’s profits increased.”

CONTRACT FARMING PROLIFERATES THANKS TO CHICKENIZATION

Regardless of these facts, Jorge plans to sell his chickens to Tyson because he has no other option. However, before he can, Jorge must sign a contract with terms favorable to Tyson. Sure, Jorge technically can choose not to, but what’s his alternative?

These contracts are a trojan horse through which Tyson can erode farmers’ freedom. Now that Jorge has signed the contract, Tyson strips away almost all decision-making power.

As Zephyr Teachout explains in her book, Break ‘Em Up, Tyson now controls a litany of decisions that previously would have been left to Jorge: what feed to use, what kind of chicks to raise, what medicines to use and when, which technicians to use, what lighting and watering schedules to adhere to, how to design and build chicken houses (which Jorge has to carry the debt for), when to upgrade buildings, what experiments to run on the farm, and more.

No longer can Jorge use his own ingenuity, wisdom, or common sense to determine how best to run his own farm on his own land.

Craig Watts (back right) stands with his wife Amelia, a teacher, and his three kids. Watts worked 24 years as a contract chicken farmer for Perdue, one of the Big Four chicken monopolies. After Watts blew the whistle on corporate misconduct, Perdue repeatedly attempted to intimidate and discredit him. Meanwhile, the Perdue family heirs have amassed a net worth of more than $3.2 billion. Photo by Craig Watts, available via Farm Aid.

CHICKENIZATION DESTROYS OPEN MARKETS

When Jorge does raise chickens to sell to Tyson, he’s forced to remove himself from open and competitive markets, and instead must participate in what’s called the tournament system of pricing.

Tyson argues the tournament system rewards performance because farmers earn more if they deliver fatter chickens relative to their neighbors. Left unspoken is how farmers like Jorge are supposed to better fatten their chickens when Tyson controls the major decisions about how to raise them.

In fact, Tyson has been accused of abusing this decision-making power and retaliating against farmers who complain. A farmer dared to question how little they’re paid? See how they like their check when Tyson gives them subpar feed or diseased chicks. Maybe they’ll think twice next time. Oh, and if any of these issues lead to a dispute between the farmer and Tyson, then the farmer must keep it a secret.

Jorge has heard stories like these, so he shuts his mouth and tries to stay in the good graces of Tyson. He usually manages to deliver some well-fattened chickens relative to neighboring farms. While that means a bigger check for Jorge, it doesn’t automatically mean that Tyson will be paying for it.

Instead, it’s Jorge’s neighbors ranked at the bottom of the tournament system that week who are forced to take home less pay, so the farmers ranked at the top can take home more. The tournament system keeps Tyson’s costs more predictable when it comes to paying farmers as a whole. But the payments individual farmers receive from Tyson can fluctuate wildly, without farmers being able to learn why.

CONTRACTS RESTRICT FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS

This scenario is possible because the contract terms also ensure that Tyson controls access to the most important data about each farm. Jorge is left in the dark when Tyson conducts experiments like trying a new mix of feed, which may affect his performance in the tournament system (and therefore his paycheck).

If Jorge tries to talk with neighbors about seeking better terms, the contract prohibits him from discussing key topics like prices or farm operations.

Tyson’s contract also requires Jorge to agree to arbitration provisions that force farmers to resolve disputes in what amount to private courts rather than public ones. Jorge is forced to forgo rights that most of us take for granted in our public court system. That includes various protections like the right to a public trial, right to a trial by jury, right to appeal, baseline rules of evidence, ability to join with others in a class-action lawsuit, and more.

This private court system of arbitration is governed by private judges who mete out verdicts while often being paid by the same corporations that farmers are seeking remedy from.

Jorge’s life—from how he runs his business, to what he’s able to provide for his family, to his very freedom of speech—is now largely controlled by Tyson thanks to the chickenization model propped up by today’s disparity system.

TOO MANY AMERICANS ARE LIVING UNDER TYRANNY

Even if Jorge wanted to get out of the chicken business, he can’t. From hogs to corn to soybeans and beyond, nearly every sector of the ag economy today features its own monopolies that reduce farmers to mere cogs in machines with less autonomy, independence, and prosperity compared to prior years.

Timothy Wise notes in Wired that today’s agriculture system is so lucrative for corporate agribusiness that they spend more money on lobbying than the defense industry. As farmers are driven to deaths of despair and our environment is pillaged, the rich get richer.

Across the country, too many Americans are living under tyrannical conditions thanks to this disparity agriculture system that serves only the wealthy few, and they can’t even speak out about it for fear of literally losing the farm.

Eleanor Roosevelt (left) chats with Henry A. Wallace (right). Roosevelt and Wallace shared strong views on issues like advocating for parity, with Roosevelt saying Wallace was “peculiarly fitted to carry on the ideals which were close to my husband’s heart.” However, they eventually grew apart due to growing foreign policy disagreements. Photo available via the Wallace Centers of Iowa.

ELIMINATING FARM SUBSIDIES WITHOUT PARITY IS MISGUIDED

Worse yet, instead of fixing it by restoring the parity system they broke, Congress uses farm subsidies in a half-hearted attempt to make farmers whole. These subsidies usually only recoup a fraction of farmers’ lost revenue compared to what they’d earn if corporations simply paid fair prices like they did before. At the same time, the burden of paying fair prices is shifted from corporations to taxpayers.

When farm subsidies don’t cover the gap between farmers’ production costs and their market price (which they don’t today), Congress guarantees that farmers will fail. Given that reality, calls to eliminate all farm subsidies without restoring a parity framework first are misguided and would only cause more harm.

This doesn’t mean that farmers like subsidies, or “charity.” They want parity. Indeed, thousands of farmers converged on Cedar Rapids, Iowa in 1985 for a taping of the Phil Donahue Show to deliver exactly that message. “We’re setting ourselves on fire out here,” one farmer exclaimed. She continued, “I don’t want your damn charity. I don’t want your subsidies. I want a price in the market!” The crowd thundered in applause.

This chart shows how even with subsidies in today’s disparity system, farmers come nowhere close to achieving the living wage-level of market prices that grew the middle class during the parity years. Chart by Brad Wilson, available via Democratic Party Farm Programs slideshow (slide 40).

DEMOCRATS CAN FIGHT FOR RURAL AMERICA AT THE FEDERAL LEVEL

Democrats should be leading the charge to fix this unjust system.

At the federal level, candidates could campaign to take on corporate monopolies like Cargill and Tyson and fight to restore parity as part of a rural Bidenomics agenda. Family farm movement leaders like Brad Wilson have suggested we could start by reintroducing price floors at something like 50 percent of parity prices and proceed to phase in full parity over a span of years.

As Democrats fight for parity, rural advocacy groups like Farm Action, Farm Aid, and the National Farmers Union offer additional commonsense ideas in line with President Biden’s efforts to promote competition and help small businesses.

That includes bipartisan policy ideas, like those put forth by Republican Senator John Thune of South Dakota and Representative Nancy Mace of South Carolina, in partnership with Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio and Representative Dina Titus of Nevada on everything from strengthening local meat processors to challenging corporations’ ability to force farmers to pay checkoff taxes that go toward lobbying against their own interests.

President Truman delivers a major address in front of 80,000 people at the 1948 National Plowing Match in Dexter, Iowa. He attacked the 80th Congress for its record regarding the American farmer, and specifically attacked Republicans for their opposition to parity. According to the Harry Truman National Historic Site, this speech is considered one of the most important of his 1948 Whistle Stop campaign that turned the tide of the election and returned him to the White House. Photo available via the Dexter Museum.

DEMOCRATS CAN FIGHT FOR RURAL AMERICA AT THE STATE LEVEL

At the state level, candidates could fight for ideas that complement parity in line with how Bidenomics focuses on empowering workers. That could mean new protections for farmers, deriving inspiration from past legislative proposals like former Iowa Attorney General Tom Miller’s Producer Protection Act.

These protections include ideas like banning companies from making contracts with farmers confidential, requiring contracts to be posted online to create a transparent market, banning companies from retaliating against farmers who complained or tried to join an organization like a growers’ union, as well as giving farmers the right to cancel any contract within three days of signing it so a lawyer has time to review it.

Candidates could further bolster this agenda by fighting for policies to revitalize local journalism, increase access to reproductive care via independent pharmacies, and protect individuals from having their property stolen by Wall Street. All of those ideas would strengthen rural America in particular, while benefiting the entire country as well.

A poster promoting an upcoming visit to Iowa by then-Senators John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson as they campaigned for the White House in 1960. The poster highlights the Democratic Party’s support for parity, which JFK would talk about at length during his visit. Photo available via the Pop History Dig.

A RENEWED DEMOCRATIC VISION FOR RURAL AMERICA

Working as a team, Democratic candidates at all levels can lead the fight for parity and once again build a rural economy that “grows from the middle out and bottom up,” in the words of President Biden.

If we build a parity system that is renewed for the 21st century, we can build a rural economy that helps to solve our biggest problems as a society.

That means an America where farmers, farm workers, and meatpacking workers can earn a living wage and enjoy increased labor protections, rather than suffer continued exploitation.

An America with lakes, rivers, and streams that people can drink from and swim in free of pollution.

An America where national security is strengthened with fair trade and resilient supply chains, rather than weakened by extremist ideology made more appealing to victims of disparity.

An America where small towns and big cities alike thrive from shared prosperity.

An America where you can stay where you grew up, and your ability to make a living isn’t determined by your zip code.

An America where farmers are rewarded for storing carbon, using less fertilizer and pesticides, and conserving natural resources, rather than penalized.

An America where Democrats start winning rural voters again. We can do all this and more if we borrow a page from the Bidenomics playbook. That means laying out a vision to reorient rural policy away from the status quo that breaks the spirit of rural America, and use it to break the power of the corporations that got us here.

American labor leaders Dolores Huerta (front) and César Chávez (back) in profile. Huerta and Chávez co-founded what would become the United Farm Workers (UFW) union. By fighting to restore parity and update it for the twenty-first century, Democrats can create a rural economy where farmworkers are strengthened too. Photo by Jon Lewis, available via Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

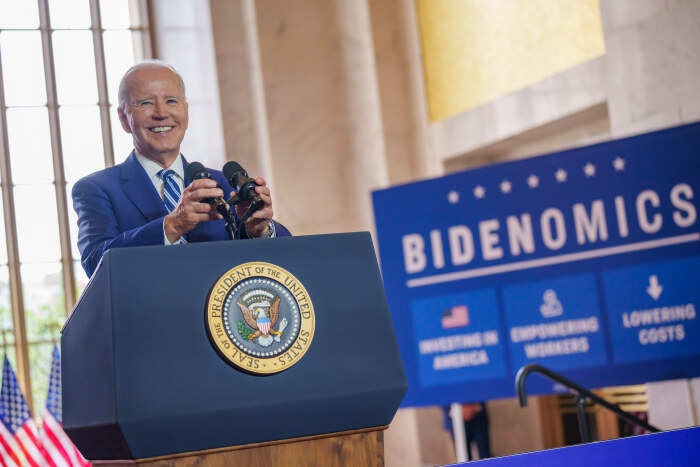

Top image: President Biden delivers a major address on “Bidenomics” — his vision for growing the economy from the middle out and the bottom up, not the top-down — at the Old Post Office in Chicago, Illinois. Photo by The White House, available via Twitter.

6 Comments

This is very interesting...

…but I would want to know a whole lot more about how natural resources fared under parity. Because I’ve seen photos of awful erosion and gullies from that era. And A SAND COUNTY ALMANAC, published in 1949, was largely about the Thirties and Forties, and it describes land and water abuse by farmers and landowners, in the Upper Midwest and elsewhere, as horrifyingly common.

PrairieFan Thu 20 Jul 1:27 AM

Capitalism is the problem that your solutions won't address

I’ve known Scott for quite a while going back to when he was a volunteer when I worked on the Edwards campaign. His decency and commitment to making the world a better place goes without question. But he’s barking up the wrong tree here. Scott’s hope is that “Parity” will inspire voters sufficiently to change our current dismal state of politics. This presumes that we actually live in a society where the majority rules. They don’t. A minority of very wealthy members of the owning class very largely determine what happens here. Don’t take my word for it. Gilens and Page conducted a study looking at nearly 1200 instances where “We the People” wanted something that organized business interests did not want. They concluded that the People have “no significant influence on the outcome.” We need far more than electoral mobilizations and a good place to start would be to raise consciousness about the true nature of the social order we live in and the range of solutions that realization opens up are far more promising.

Redragon52 Thu 20 Jul 8:59 AM

As far as you know...

…does it make any significant difference if a state has an initiative/referendum option? Iowa doesn’t, of course, but twenty-six states do.

PrairieFan Thu 20 Jul 3:42 PM

Economics versus Family Values?

Scott makes excellent points about rural and agricultural economics. The problem is that the Democrat have always had the superior economic argument, be it the Populist movement of the 1890s, the Roosevelt New Deal farm programs and rural electrification of the 1930s or Joe Biden’s drive to fix rural bridges and expand the broadband network. Those worthy achievements have fallen short politically to genius of the Republicans at using social and cultural issues to attach rural America at the hip of the Republican Party. Through the 1920s Republicans used the Prohibition issue to insure the votes of what was then known as the “Farm Belt” all while pointedly ignoring the suffering of agricultural and rural America. Rural Electrification, promoted by FDR and a Democratic congress, did little to break the permanent Republican majority in the countryside. It is no accident that the social issues of today, abortion, gay marriage and now school bathrooms and sports competition, are promoted most vigorously by the rural interests who still predominate in state legislatures and in Congress. The result is that city folks’ tax money will be used to fix rural bridges and broadband, all while rural-oriented governors and legislators approve of food, health and education policies that work to the specific detriment of urban America.

Dan Piller Fri 21 Jul 6:58 AM

Parity

The FDR/Henry A. Wallace Farm program (supply management/price support) had a built-in conservation (cropland setaside) element; and a BIG soil erosion control element.

The fence to fence program of the late 70s – 80s and the resulting monocrop/CAFO/ethanol model was promoted by the GOP and misguided Democrats. We’re left with farm consolidation and withering rural life quality.

11111 Thu 3 Aug 7:40 PM

Farm Parity

The NFO tried collective marketing in the late 50s-60s. It was subverted by Farm Bureau and right-wing folks. In theory, a good idea.

It did prove that a quasi-public system (USDA parity program) is the only way independent farmers can stabilize their sector of the food chain over time.

Farmer share of the food dollar otherwise shrinks !

11111 Thu 3 Aug 7:51 PM