This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

According to Portrait and Biographical Album of Muscatine County, Iowa (1889), Editor-publisher John Mahin “was secretary and manager of the Soldiers’ Monument Association of Muscatine County which erected the beautiful shaft to the memory of the heroes who fell in the cause of Union and freedom upon Southern battle-fields, and which now ornaments the court-house square of Muscatine.”

Author Lee Miller, while researching his 2009 book, Crocker’s Brigade, “noticed a conspicuous disparity between the number of names displayed on the memorial and the actual number of Muscatine County soldiers who died during the Civil War.” (Blurb on his second book, Triumph & Tragedy, 2012.)

“The explanation was that when the memorial was built in 1875, the full account of Iowa’s Civil War dead had not been completed. Miller became chairman of the Muscatine County Civil War Memorial Committee and raised over $270,000 for a new memorial.… This new monument bears the full complement of 513 names of Muscatine County men who died in the Civil War.”

Lee’s research showed early 20th century plaques had not solved the problem of 60-plus names left off in 1875, so he started an initiative to add missing names. Then it turned out the marble column was deteriorating dangerously.

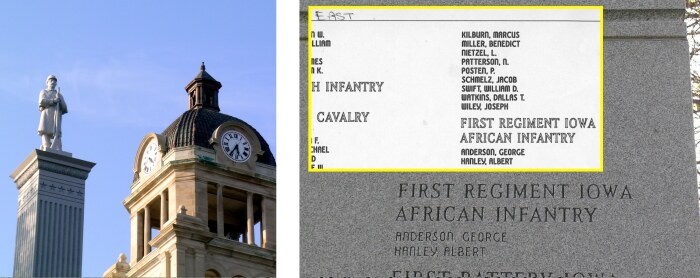

The rededication on July 2, 2011, was a grand and solemn occasion. As the emcee, I apologized for a particular honest mistake, a wrong name caught too late. We had listed a wrong brother as having died in the war. Even worse, those brothers were two of only five local residents who served in the regiment Alexander Clark helped organize.

Iowa’s “colored regiment” had never been acknowledged at the courthouse square. Kent Sissel, restorer of Clark’s house, had urged us not to overlook the Black soldiers again. The 1st Iowa Infantry of African Descent (later 60th U.S. Colored Troops) was created in July 1863. Clark, their main recruiter, won sergeant-major rank although a disability kept him from serving.

E-mail from Lee, Dec. 16, 2009: “Two of these soldiers, John Anderson and Albert Hanley, died while on duty. Why these two names were not included on the monument can be only speculation.”

April 2011 e-mails between Lee and me:

Dan: “I fear I found a boo-boo! We listed George Anderson and Albert Hanley, but the online roster says the Anderson who died was John. Do your records show otherwise? Maybe I gave you the wrong name and never caught my mistake. I’m really embarrassed to be just now seeing this. I sure hope I’m wrong! Do you know if the names have been engraved yet?”

Lee: “This is not your fault! I prepared the list and evidently put George’s name on instead of John. I even checked and double checked the list and still missed it. Unfortunately, the engraving is done now so we will have to live with it. If you look very carefully at the names that were engraved on the old monument you will find a lot of misspelled names including several with wrong first names. In our defense, I believe we did a very good job of correcting many of these and adding a lot of missing names. I’m also sure that if we did a ‘very careful audit’ of each and every name with courthouse records we would probably find some more boo-boos. This doesn’t excuse my mistake on this one though.”

Dan: “Not gonna blame you, Lee! I’d read through ALL the names looking for typos, but I had a special interest in getting these two right, so I should have double-checked that we had the right guys, just to be sure. A good reminder that good spelling isn’t enough. Sheesh…”

Later I wrote: “I told Kent about this and he said he thinks it should be possible to fill George ‘with granite dust and epoxy’ and re-do as John with good result, invisible and permanent.” We did not try it.

The new monument was guaranteed “forever” according to the makers. They claimed the Vermont granite “will last an eternity.” It should last “several more centuries,” Lee agreed.

Some innocent errors become historical injustice. We hear the word “reckoning” in debates about trying to make up—somehow—for historical wrongs. I ponder reckoning.

My latest boo-boo was in last week’s column. Paul Finkelman requested this correction: “That’s the essay Finkelman is writing for the book Lost Lives Recovered, Lost History Gained, being edited by Donald Yacovone, who for many years was the research manager at the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute at and an associate at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, both at Harvard University.”

I had embellished Paul’s private note: “I am writing a scholarly book chapter on Clark for a collection, being edited by Donald at Harvard’s DuBois Center.” I jumped to the wrong conclusion and wrote “to be published by.”

Crow is best eaten warm, they say.

Next time: Worthy to be trusted with the musket

# # #

Top image: The Civil War monument at Muscatine County Courthouse. Close-up: The wrong-name typo laser-cut in granite; inset shows paper proof when it could have been fixed. It should say John, not George.