This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

The first draft of history is the newspaper. Or used to be.

Certainly the Muscatine Journal archive is a main source about Alexander Clark, maybe the most important one. As early as 1853, the editor saw his neighbor’s life as news worth reporting. As Clark’s fame grew from local to national and beyond, John Mahin’s paper supplied evidence of what was said at the time about Iowa’s champion of emancipation and equality.

During the 1880s, Clark and his son worked at publishing a leading Black newspaper in Chicago, The Conservator. Bits of it quoted or mentioned in the Journal are some of the best remnants of an undertaking that put Clark on the executive committee of the national Black publishers association.

If you’ve followed these columns—this is No. 38 since early February 2022—you might be surprised, as I am, that a modern editor gives license to pursue my passion for the story of my “brother from another mother.” Mounting the soapbox has fed my determination to help win National Historic Landmark recognition for his 1878 house.

Writing week after week allows me to dig into details and explore the grand narrative in a public way. It’s an extraordinary opportunity to set the record straight where earlier tellings were sloppy.

I learned a lifelong lesson when a single misspelled name meant automatic F for the assignment. That was the rule in a newswriting class I took back when we aspiring journalists pounded stories on upright manual typewriters.

Accuracy was that important, the prof insisted. If you screw up names, readers won’t trust your other facts.

Several jobs involved me in writing and publishing, but a year at the Journal was my only experience of an actual newsroom.

“Two sets of eyes” was the rule where we stood to proofread pages. When you weren’t busy with something else, you took a turn scanning for errors and marking any found. Your initials went at the top to show you’d read and approved the page. Without two sets of initials, it wasn’t ready for publication.

More than once the editor tugged at the sheet I was scanning. “Sign it,” he’d say. “We need it now.” But I never did, not until I could certify accuracy. I accepted the industrial pace, but my initials were my reputation.

Some days I shake my head and wonder if J-schools still teach accuracy, but sloppiness isn’t intentional. My sympathies are always on the side of the rushed writer and the harried editor—too often the same person these days.

So, what middle initials?

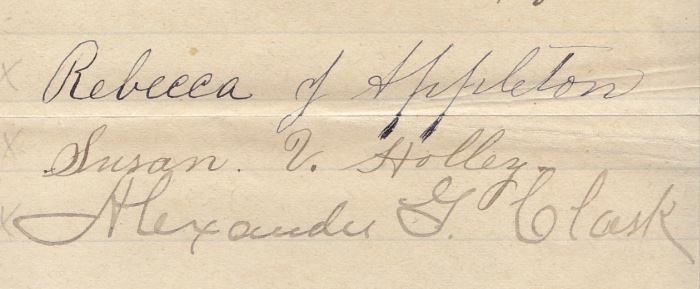

First: daughter Susan, known as Susie well past her marriage to the Rev. Richard Holley. Her middle initial was not the “B” shown in court documents when she integrated public schools in Iowa. In newspaper mentions throughout her life she is always Susan V. or Mrs. S.V. Holley.

Just last week I discovered a birth record from Davenport for their second daughter, born Nov. 29, 1881. Mother: Susan Virginia Holley. Maiden name: Clark.

Let the record henceforth show “V” not “B.”

Second: father and son. No middle initial for Clark senior. He was always known as Alexander or Alex or Aleck. Later in life he held fancy titles befitting the Masonic grand master (e.g., Worshipful) and “the Honorable” and “Excellency” when serving as Minister-Resident and Consul General of the United States to Liberia.

The son, Alexander junior, used middle initial “G” for Griffin, his mother’s maiden name. He went by Alex and A.G. As a lawyer and Mason he became known as Alexander G. Clark, Jr.

The father gained a middle initial about 80 years after his death—around the time his residence got rescued from demolition as a U.S. Bicentennial project and gained listing on the National Register as the Alexander G. Clark House.

Picky picky? Such details matter to historians and, no doubt, to officials at the National Park Service where we must make our case for upgrading Clark’s federal designation from state “significance” to national.

Our constitutional-law-historian advisor Paul Finkelman agrees there’s no “G” for Clark senior.

“There is no ‘G’ in the census for 1850, 1860, 1870, or 1880 and he is in Liberia by 1890,” he wrote. “The ‘G’ seems almost certainly an ‘invention’ of the 20th century. … So, because [the son] was ‘Junior,’ 20th century people assumed that Senior had ‘G.’ That would be the ‘modern’ convention. I know in the 17th and 18th centuries ‘juniors’ often had a different initial. In the 17th and 18th women were also ‘junior’ named for their mother. I suspect this is true for 19th as well. And I will say that in the piece I am writing.”

That’s the essay Finkelman is writing for a book to be edited by a scholar associated with the DuBois Institute at Harvard headed by Henry Louis “Skip” Gates, Jr. Talk about opportunity to set the record straight!

Next time: A typo cast in stone

Top image: The signatures of Alexander Clark’s children, 1891.