This post was supposed to be a book review.

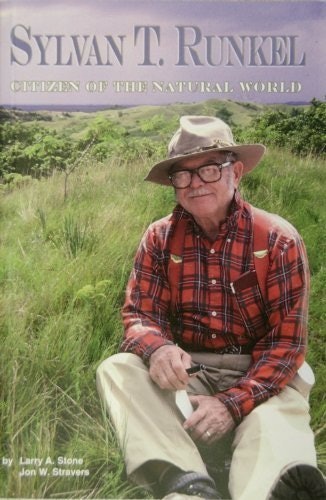

I bought a copy of Sylvan T. Runkel: Citizen of the Natural World at the Okoboji Writers’ Retreat in September, thinking it would be perfect to review for my Iowa wildflowers series. Runkel co-authored some of the best Iowa wildflower guides, and I’ve used Wildflowers of Iowa Woodlands and Wildflowers of the Tall Grass Prairie countless times.

Co-authors Larry Stone and Jon Stravers both knew Runkel and interviewed many of his friends, relatives, and former colleagues while researching their biography. As expected, I learned a lot about how the famous conservationist grew to love the outdoors and became passionate about native plants and natural landscapes.

The book also struck a chord with me as I’ve been coping with the most physically challenging year of my life.

As a child, Sylvan Runkel explored the wooded Mississippi River bluffs near his family’s home in Moline and spent ten summers with grandmother Becky Jane, who lived a frontier lifestyle in a literal log cabin in Illinois. Becky Jane taught Sylvan and his sister about many woodland and wetland plants.

Sylvan got a forestry degree from Iowa State University but struggled to find a steady job in that field during the Great Depression. His big career break came after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt created a Civilian Conservation Corps. Sylvan’s favorite forestry professor was put in charge of CCC work on private land conservation in Iowa, with a focus on reducing erosion to avoid a Dust Bowl scenario on our farms.

As a CCC camp supervisor, Sylvan worked on tree-planting and forest management projects, then moved to the newly-formed Soil Conservation Service in 1935. In that role, he wrote newspaper columns and traveled the state educating landowners about erosion control, soil health, and wildlife habitat.

His life changed course during World War II, when Sylvan enlisted in the Army Air Corps as a 35-year-old with young children. For about two years he remained stateside, learning to fly gliders and serving as an instructor for other glider pilots. Then he received combat training and was sent to England in the spring of 1944. Sylvan was part of a D-Day wave of gliders, on a mission to land behind enemy lines in France.

But the glider he was on crash landed, killing the pilot and at least two other crew members. Sylvan suffered several broken bones in his leg as well as a broken elbow and broken teeth. He lay on the field helplessly as a German bullet smashed his kneecap hours later. It took days to get back to a military hospital in England, then months before he was well enough to return to the U.S.

Sylvan spent the better part of the next three years in military hospitals, undergoing a dozen operations and repeated courses of treatment for a bone infection. Eventually his knee was fused, forcing him to walk with a limp for the rest of his life.

As I continued to read about Sylvan’s work with the Soil Conservation Service and other passions in life (Scouting, camping in mountain country, relaxing at a primitive cabin in the Boundary Waters), I found myself returning to the chapter about his wartime service and recovery. How did this man with a permanent disability stay in a physically demanding job, let alone lead children and adults on nature hikes and backpacking trips in his spare time?

When an SCS coworker once asked him why he limped, Sylvan replied wryly that he was thankful he was limping—it was either be limping or be dead.

“I guess I would be classified as a sidehill gouger,” he later joked. “I can walk around a hill one way, but the other way is pretty tough.” Sylvan somehow kept his positive outlook, despite his long hospitalization and painful injuries. “What cannot be cured, must be endured,” he believed.

Sylvan’s first wife died in the late 1940s after a long bout with undulant fever. He was a single father to three children for years, then remarried and had three more children during the 1950s. He regularly took his kids hunting or on nature walks. While in his 60s, Sylvan hiked to the top of Mount Baldy in New Mexico (12,441 feet elevation) three times with groups of Boy Scouts.

When he was preparing for a trip, Sylvan regularly hiked around Des Moines to get in shape. “You could always see him, the years he was getting ready to go, in his training,” [Scouting friend Bill] Darby said. “He walked a 5-mile stretch…a regular route. You’d see him every morning out there.”

I’m dumbfounded just typing out those words.

Early this year, I severely fractured my ankle in the most boring way possible: slipping on the ice while walking my dog. The injury was nothing like what Sylvan Runkel went through, but it was life-changing. I went from walking three to five miles a day to not being able to walk for the rest of the winter and most of the spring. The pain (worse than anything I had experienced) gradually subsided over the next several months, but one of my broken bones healed at a slightly wrong angle and will eventually require more surgery. In the meantime, I will be walking with a limp for many more months, possibly for the rest of my life.

I can’t convey how disruptive this injury has been, physically and mentally, to my work. It obliterated my ability to cover the Iowa legislature’s 2022 session in the usual way. Months later, I was unable to pull together many of the stories I would normally write during an election year. Aside from the many hours spent at doctor’s appointments and physical therapy, I’m so much slower at everything now. Even though I can walk the dog again without assistance—for a few miles some days—it’s uncomfortable, and takes twice as long. At home, I don’t concentrate as well, which has affected my productivity as a writer.

I have found it hard to stay in a positive mindset, especially since learning that even in the best-case scenario following future surgery, I will never be able to do some activities I used to enjoy, like running. During the spring, summer, and fall, my injury mostly put me off wildflower spotting on trails and prairies like I’ve done regularly for the last twelve years.

This book by Stone and Stravers forced me to face facts. Dealing with a much worse injury for decades, Sylvan Runkel kept going out there with his walking stick, leading groups through the fields or the woods or the Loess Hills or more rugged terrain out West. He wasn’t focused on not being able to jump trains or climb trees and mountains, the way he did as a young man.

I’ve been feeling apprehensive about having to navigate snow and ice this winter, and was too worried about balance issues to get back on a bicycle this summer. Sylvan regularly flew small planes after almost losing his life in a crash.

In retirement, he kept up a busy travel schedule with conservation and education work, and served on many state or nonprofit boards. He helped preserve many natural areas and raised public awareness about the unique Loess Hills landscape. And he kept hiking.

Sylvan liked to find a trail where he could shout out the names of his favorite plants: “RATTLESNAKE” fern in the woods, or “RATTLESNAKE” master on the prairie, or “WAHOO” tree along a fencerow. He would approach the plant while talking quietly, then grin with delight when his outburst startled his companions.

Sylvan sometimes brought home edible plants and roots. He and his wife Bernie once served friends a dinner including “wild leek soup, evening primrose roots, spring beauty bulbs, creamed milkweed on toast, steamed nettles, morel mushrooms, and cattail shoots.” Another biologist recalled his colleague demanding to stop the car when he saw cattails blooming near the side of the road. “The two men got out and gathered a bag of cattail pollen for Sylvan to add to his next morning’s pancake batter.”

I’m so glad I was able to meet Larry Stone in Okoboji and buy a copy of his book. Learning more about Sylvan Runkel inspired a Thanksgiving Day resolution: I will be grateful for the mobility I have, and I will get outdoors more often during 2023. Maybe the brace I’ve been fitted for will help me walk more confidently on uneven ground. If not, I’ll get a walking stick.

Top image: Photo of dried native plant arrangement provided by Mike Delaney, using plants and seeds from his restored prairie in Dallas County. The tall plant in the middle is big bluestem. The tall plants on either side of that are Indian grass. The light brown near the center of the bouquet is Missouri goldenrod. The darker seed heads near the right are stiff goldenrod. The large pods on the left are common milkweed. The small darker berries near the lower left are coralberry.

2 Comments

Grateful for this post

Laura,

I am grateful for this honest and clear-sighted post. And so sorry that the injury has had such lingering consequences.

I like the idea of a walking stick. I recently read Kim Stanley Robinson’s, The High Sierra: a love story. He talked about how walking sticks have kept him active and upright in the Sierra through his 60s and (hopefully) through his 70s, too. May you have many ambles in your future shouting the names of old botanical friends.

Steve Peterson Sun 27 Nov 10:17 AM

Thank you for sharing, Laura...

…and I’m so sorry about what happened to your ankle.

I’m sure other readers are also hoping hard that the long-term results of your injury will turn out to be at the very mildest end of the range of possibilities. And may you and your walking stick travel far and happily.

PrairieFan Thu 8 Dec 5:24 PM