This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

Theodore “T.S.” Parvin came to Iowa in 1838 with Robert Lucas, the first territorial governor, and soon settled at Bloomington—future Muscatine—to serve as district prosecutor.

His uncle, John “J.A.” Parvin, arrived less than a year later. Together they started one of the first schools in the territory. Both would achieve life-long reputations as champions of education.

J.A. was a founding member of the Methodist Episcopal church and the first temperance society of the territory. At first J.A. taught school and ran a general store. (Josiah, brother of J.A. and father of T.S., ran a hotel here for a while, too.) I’ll write about T.S. some other time.

In 1843, before we had mayors, J.A. was elected president of Bloomington. Starting in 1846, he served four years as clerk of the district court. In 1850 he was elected a representative to Iowa’s third General Assembly. There he won passage of the bill changing the name of Bloomington to Muscatine and supported efforts to prohibit liquor selling. In 1854 he was elected mayor of Muscatine.

I’ve been telling about the politics of race in Iowa leading up to the Civil War, laying out background for the equal-rights victories of 1868. I invite you now to watch the evolutions of J.A. Parvin and the Republican newspaper that backed him.

Early in 1856, Parvin was a delegate to the convention that organized Iowa’s Republican party. That fall the Muscatine Journal endorsed his candidacy for representative to the forthcoming state constitutional convention. It was a partisan contest.

October 20, 1856:

Mr. Parvin always acted with the democratic party until it became a covenant-breaking and slavery-propagating organization. He renounced his allegiance to it when the Missouri Compromise was repealed. He is now a Republican…and an ardent opposer of slavery extension.

October 24:

Mr. Parvin said he had been called a [N-word] “worshipper” and would vote for granting negroes the right of suffrage. This he denied and stated emphatically that he was opposed to extending the negro the right of suffrage. Thus have the lying mouths of contemptible politicians been closed, and Mr. Parvin stands today before his fellow-citizens with a clearer and better record than either of his opponents.

He won and was chosen president pro tem when the convention convened at the capitol in Iowa City on January 19. The delegates deliberated until March 5.

Acknowledging resolutions received from a convention of “colored” Iowans back in Muscatine, Parvin moved to consider “making provision for the education of the children of blacks and mulattoes.” Next he submitted a petition from 129 Muscatine citizens protesting “any provision again imposing upon the black population of this State the disabilities in regard to giving evidence in Courts, and the holding of property.”

As I reported last week, the controversy ensuing from these Parvin initiatives led to a decision by the convention to put a separate question in front of voters asked to ratify the new constitution.

“Thus the Republicans in the Convention avoided the delicate task of settling the question of negro suffrage.” (Erik M. Eriksson in Iowa Journal of History and Politics, 1924)

With 20-20 hindsight, are historians too harsh in their assessments?

Few questioned that most Iowans felt open hostility to the idea of full political citizenship for the Negro. To push this issue in the convention courted disaster at the polls for Republicans. On the other hand, they constantly preened themselves in public on their idealism and humanitarianism. … They cleverly extricated themselves from their dilemma by recourse to the most basic of all democratic processes—the referendum. With a vote of 23 to 10 the Republicans pushed through an amendment to have a separate ballot attached when the vote on ratification of the Constitution went before the people. The population of lowa rather than the Republican delegates would be forced to decide whether to delete the word ‘white’….

James Connor in The Annals of Iowa, 1970

The outcome? In August 1857, Iowans approved the new constitution and then put themselves on record for white supremacy: 49,387 to 8,489.

While Democrats tried to revive segregationist sentiment in the run-up to the regular elections in October, egalitarians kept their heads down. The new Republican party passed its big test, electing former Muscatine resident Ralph Lowe as governor.

But one former Democrat turned Republican paid the price for his outspoken role in the constitutional convention. A few days before his 50th birthday, John Abbott Parvin lost his bid for election to the state Senate.

Muscatine Journal (quoting the Davenport Gazette), October 24, 1857: “The Republicans elected their whole ticket in Muscatine county with the exception of Mr. John A. Parvin, their candidate for Senator. We much regret Mr. Parvin’s defeat, as he is a man of talent and sound judgment, as well as thorough going Republican.”

Next time: Dueling editors

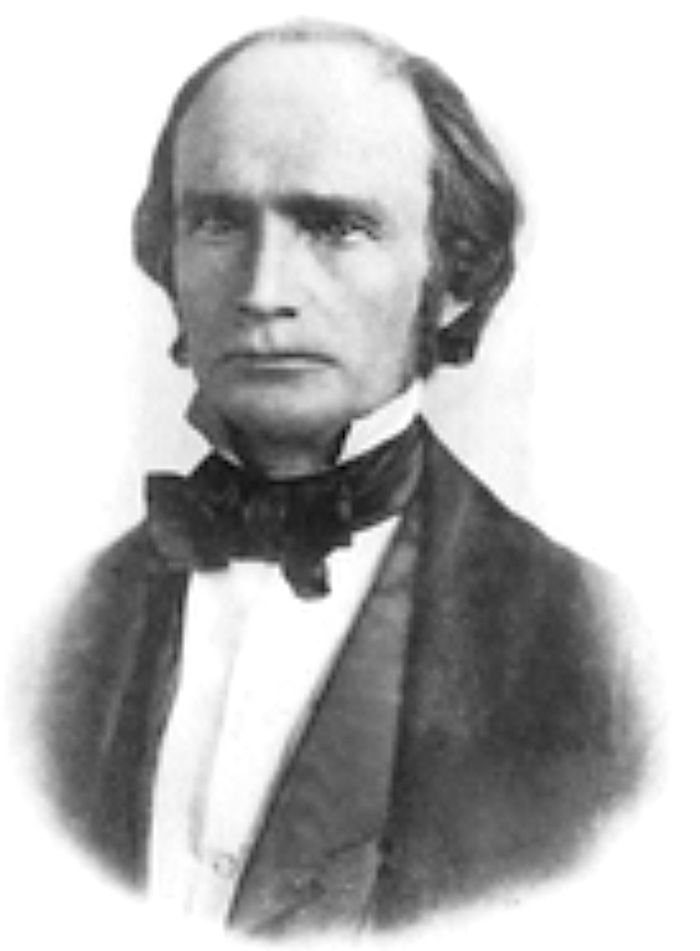

Top image: John Abbott Parvin (1807-1887)