This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

“We never had race trouble here.” I hear this often. I call it the Nice Iowans fairytale.

Take this comment posted on the Muscatine Journal’s website recently: “Throughout all of lowa, Black children regularly attended school with their White neighbors at this time, and at all times in history. lowa has never had any such thing as ‘segregated’ schools—ever.”

The commenter asserted that a “small pocket of [racists] tried to get the racism and segregation going, but this Court Case [the 1868 Iowa Supreme Court landmark Clark decision] reaffirmed that we lowans (as a whole) don’t do that.”

It is true that our state constitution got revised in 1857 to assure public education for all lowa youth; however, it made “separate but equal” perfectly legal until the Clark ruling, and not only in a few racist enclaves.

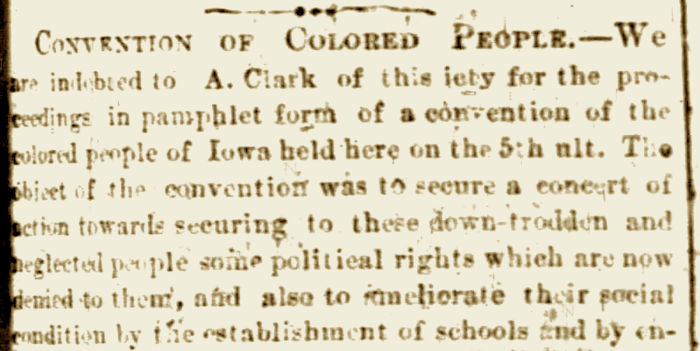

Muscatine Journal, February 6, 1857:

We are indebted to A. Clark of this city for the proceedings … of a convention of the colored people of Iowa held here….

It was resolved to petition the Constitutional Convention to extend the right of elective franchise to native born negroes and to bestow upon them all the rights and privileges of citizenship. … The committee on education recommended the utility of pressing forward to obtain education over every opposition, as upon this “depends the moral and political elevation of the colored race.”

The delegates convened at the capitol in Iowa City on January 26 and worked until March 5.

Historian Robert Dykstra: “Prompted by the recent colored convention’s resolutions, Muscatine’s delegate, John A. Parvin, moved that the committee on schools consider ‘making provision for the education of the children of blacks and mulattoes.’”

Parvin submitted a petition “signed by Henry O’Connor and 128 other Muscatine citizens—Democrats and Republicans alike—protesting ‘incorporation in the Constitution of any provision again imposing upon the black population of this State the disabilities in regard to giving evidence in Courts, and the holding of property.’”

Muscatine Journal, March 2, 1857:

We learn from a private source that there is no probability of this body changing the Constitution in regard to Negro suffrage. Some members are in favor of submitting the question separately and distinctly to the people at the same time a vote is taken on the Constitution, but it is doubtful whether even this will be done.

On March 6 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that people of African descent are not citizens of the United States, whether enslaved or free.

Despite intraparty Republican anxiety, a side question would appear on the ballot: “Shall the word ‘white’ be stricken out of the article on the ‘Right of Suffrage?’”

Muscatine Journal, April 17:

Not more than two thirds of the voters in the State will vote on it at all, and a minority of these will be in its favor. There is not the most distant probability that the measure will be adopted. Our main object, therefore, in this article is to repel the insinuation of the Democratic press that the Republicans claim negro suffrage as a tenet of their party faith.

The executive committee appointed at the January “colored” convention announced another convention for June 2 to be held in Muscatine.

Muscatine Journal, May 4:

From a circular handed to us by Alex Clark, we learn that it is “for the purpose of taking into consideration the proposition now before the people, shall the word white be struck from the new Constitution?”

Although we are not prepared to vote for negro suffrage, we approve of the course to be adopted by this convention. No harm can result from a discussion of this great question of human rights. We hope these advocates for the colored race will not be insulted or derided in any part of the State, but will be listened to with candor. If they can succeed by fair means in convincing a majority to vote for the proposition, we shall cordially acquiesce

In August 1857, Iowa voters approved the new constitution by 51 percent to 49 percent and put themselves on record for white supremacy “by the crushing margin of nine to one,” in the words of historian Robert Cook. A “colossal rejection of black suffrage,” in the words of historian Dykstra.

Call those voters racist, or just observe that they shared the prevailing attitudes of their day. Either way, the compromises that got the constitution passed at all actually reinforced the existing regime of exclusions against people of color.

Happily, a big shift in public attitudes occurred during the following decade. Sadly, it took a civil war to do it. The next constitution referendum was held in 1868, after the Clark decision. Those post-war Iowans removed most of the provisions privileging “white” citizens.

Spin it however you want, dear reader. Our history blows away the “No Racism in Iowa” fairy tale. Living up to equality aspirations has been a struggle.

Next time: The political price of Parvin’s petitions

Top image: From the Muscatine Evening Journal, Friday, Feb. 6, 1857.