This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

Alexander Clark’s daughter entered history in 1867 as the 12-year-old Iowan turned away from her neighborhood school because of skin color. Her father sued Muscatine’s school board and won. In 2019 the modern successors named the Susan Clark Junior High School.

Susan was born December 6, 1854. Her father had been an equal-rights activist all her life.

“[F]or the first time, so far as is known, they formally spoke up for themselves. … Alexander Clark, lowa’s most influential black spokesman, had evidently instigated the document. … Clark’s petition reached the floor of the house on January 17, 1855.” (Robert Dykstra)

The petitioners asked lawmakers to repeal the harsh 1851 update of Iowa’s 1839 Act to Regulate Blacks and Mulattoes—in “misspelled but forceful words” to quote historian David Brodnax.

We your petitioners deem it onnessary to say anything about the injustus of the Law, or its oppresstive influences upon us as free Colord Citizens of the United States of America, but we will submit it to the honest consideration of your Honorable body ever hoping that the god of heaven may gide and direct your acts in favor of Justus and opprest humanity.

Susan’s mother Catherine and sister Rebecca were among the 33 signers, and we’ll learn of others. I’ve known about the petition almost 20 years but wondered only recently about the unknown legislator in this passage by Robert Cook: “Midway through the turbulent winter session, Dr. Reasin Pritchard, an anti-Nebraska Whig from Muscatine, presented to the house a petition praying for repeal of the exclusion law.” (Baptism of Fire: The Republican Party in Iowa, 1838-1878)

A 39-26 vote blocked consideration. “Of those registering their desire to receive the petition, twenty-five were fusionists.”

Anti-Nebraska refers to opposing slavery in new territories. Fusionists refers to the coalition that elected James Grimes as governor in 1854; they would create the Republican Party of Iowa in 1856. But Dr. Reasin Pritchard? How had I missed this guy?

Jacob Pritchard was a Black man known better than Alexander Clark in the early days, judging by his frequent newspaper ads for various enterprises. For example: “Pritchard’s Refreshment Saloons [in] rooms under Hare’s Hall…ready to dispense every variety of edibles and luxuries to the hungry…Oysters, pastry, &c., always on hand.”

Jacob was among the first trustees of Bethel A.M.E. church and Clark’s partner in bringing the Black masonic order west of the Mississippi. And he was a signer of the 1855 petition. But Reasin? Apparently no relation.

Have you heard the expression “go the way of the Whigs”? It’s the political version of “go the way of the dodo”—a thing of the past. The Whigs elected two presidents during their two decades as a major party, then dissolved in 1856 over the issue of slavery.

From a report of their county convention (Muscatine Journal, July 15, 1854): “There would be a U.S. Senator elected at the next session of the Legislature, and the Whigs considered it important that he should be an anti-Nebraska man.”

Candidates got grilled, and Pritchard’s answers were satisfactory.

“At the same time he took occasion to say that he had been falsely accused of being a political Abolitionist. He had never belonged to such an organization. He was opposed to slavery in sentiment; he was opposed to its extension; but he was also opposed to meddling with it within the States; he was opposed to stealing ‘[N-words],’ and against all ‘underground railroad’ operations.”

Rep. Pritchard took office in December and helped elect James Harlan for U.S. Senate. Harlan was president of Iowa Wesleyan College and a member of the new Free Soil Party.

Muscatine Tri-Weekly Journal, January 17, 1855: “The Muscatine county delegation have not much to say, though they are always awake to the interests of their constituents and the State at large. They vote right. Mr. Pritchard has spoken on several important questions, with considerable effect.”

He voted in the 35-32 majority for “suppression of Intemperance.” He “opposed with very strong arguments” a motion favoring Dubuque railroad promoters over initiatives downstream. He introduced a bill to extend the city limits of Muscatine. He voted to elect delegates to a convention to revise the state constitution.

What kind of doctor was he? I don’t know. What else can we learn? He advertised a sale of “fine sheep” having been in Ohio “for many years engaged in the Wool Growing Business” (1852), and he showed the “Best pen of sheep” at the First Annual Fair of the county Agricultural Society (1853). That’s about it.

Journal of the House of Representatives (Iowa City, July 2, 1856): “J. Scott Richman is duly elected to fill a vacancy in Muscatine county, caused by the decease of Reasin Pritchard.”

As Judge Richman, he would rule in favor of Susan Clark in 1867.

Next time: No picture of Susan?

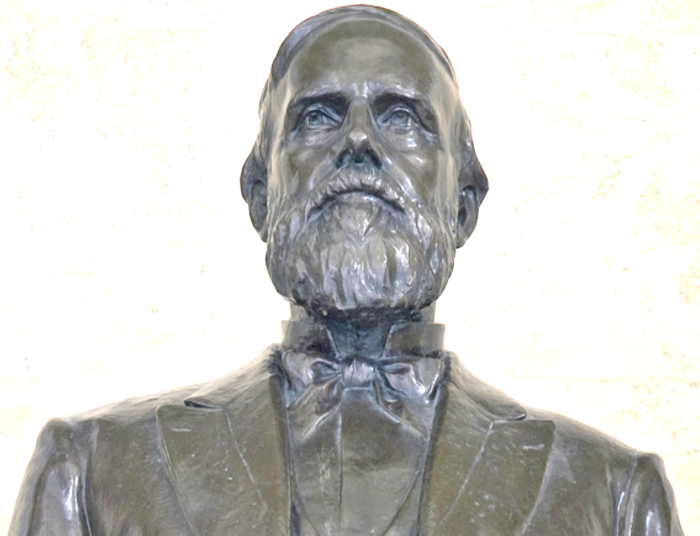

Top image: James Harlan’s statue represented Iowa in the U.S. Capitol’s Hall of Columns for 104 years until replaced in 2014 by a statue of Norman Borlaug.