Longtime advocates for access to public records in Iowa expressed concern this week about new administrative rules proposed by the Iowa Public Information Board.

The draft rules would spell out requirements for acknowledging and responding “promptly” to public records requests, but would also create a new excuse for government bodies that fail to provide timely access to records. Nothing in Iowa’s open records statute, known as Chapter 22, authorizes the board’s proposed language on “unforeseen circumstances,” nor is that concept consistent with Iowa Supreme Court precedent.

A NEW SECTION OF ADMINISTRATIVE CODE

The Iowa Public Information Board was created in 2012 and charged with enforcing the state’s open meetings and open records laws for local government entities and most of the state government’s executive branch, other than the governor and governor’s office. Its nine members are all appointed by the governor, subject to Iowa Senate confirmation.

The board has generally been sympathetic to government bodies accused of violating Chapter 22 provisions. It has dismissed most open records complaints filed against state government agencies, sometimes voting to dismiss complaints even after finding that state employees violated the law—provided that the agency promises to do better next time.

The board proposed the following new administrative rules on open records.

Some provisions could be helpful to those seeking public records. Government bodies “shall give a high priority to fulfilling requests,” and “must acknowledge” receipt of records requests within two business days. Certain state entities have occasionally ignored records requests for weeks or months, rather than expressly refusing to provide material.

The proposed rules would require acknowledgements to “include the name and contact information of the person responsible for processing the public records request.” Some state government entities funnel open records requests through email accounts that don’t include any state employee’s name or contact information, which can make it difficult to follow up on outstanding requests.

The rules also make clear that government bodies should not hold up an entire batch of records over difficulty in providing a copy of one part of the request.

Most of the problematic wording relates to reasons that justify a delay in handing over public records.

“UNFORESEEN CIRCUMSTANCES”

In a 2013 case known as Horsfield (or Horsfield Materials v. City of Dyersville), the Iowa Supreme Court held unanimously that the city’s “substantial and inadequately explained delay in responding” to an open records request violated state law. In keeping with a “longstanding administrative interpretation” of Iowa Code Chapter 22, justices found that “records must be provided promptly, unless the size or nature of the request makes that infeasible.”

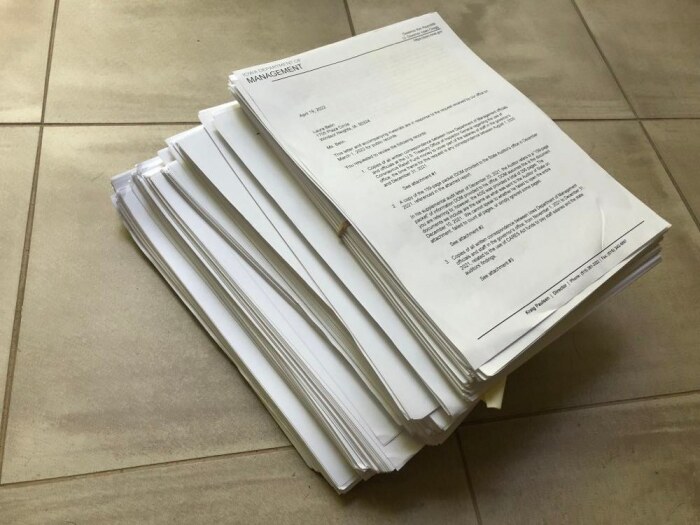

That’s a logical standard. If a request yields hundreds or thousands of pages of responsive records, it may reasonably take several weeks to compile and review the material. I have occasionally waited six to eight weeks to receive a large volume of records, such as documents related to an Iowa Attorney General’s opinion in 2017 or a late judicial appointment in 2018, or a batch of records pictured at the top of this post, which the Iowa Department of Management mailed to me in April 2022.

On the other hand, a delay of weeks or months is not reasonable if the custodian could have pulled the material together much more quickly.

Red flags went up for me and others upon reading this part of the Iowa Public Information Board’s draft administrative rules.

497—11.6(22) Factors affecting timely compliance. In assessing whether a government body provided access to records promptly, or as soon as feasible, the following factors may be considered:

11.6(1) The number of records requested;

11.6(2) The difficulty of searching for or retrieving the records requested;

11.6(3) The difficulty of formulating effective search criteria for retrieving electronic records; and

11.6(4) The existence of unforeseen circumstances that reasonably interfered with the lawful custodian’s ability to search for or retrieve the requested records.

Based on my firsthand experience, I fear that government entities could seize on any number of pretexts to delay producing records. The COVID-19 pandemic would be the most obvious example. A budget cut, or some employee taking parental or medical leave, could also be construed as an “unforeseen circumstance” making it impossible to search for requested documents for months on end.

The Iowa Freedom of Information Council, a nonprofit organization advocating for openness and citizen engagement, said in its public comment to the board that this “clear expansion of the reasons government officials may delay making records available” should be “made by the Iowa General Assembly through an amendment to Chapter 22, instead of by an administrative rule […].”

The council noted, as did Michael Giudicessi, an attorney who has litigated many open records cases, that the state legislature could have altered Chapter 22 at any time since the 2013 Horsfield decision, to add to the allowable reasons for not promptly providing records. Lawmakers have left that portion of the code alone.

Giudicessi characterized the “unforeseen circumstances” provision as “unnecessary, unworkable, and unwise.” In Horsfield, the Iowa Supreme Court “used assessment criteria that relied on objective determinations that focused strictly on the information sought without injecting the post-hoc excuses or justifications of the lawful custodian.”

Further, the Court set a standard based on “size and nature” that did not rely on a loose, ambiguous term, such as the phrase “unforeseen circumstances.” The proposed rule unfortunately would bring an unworkable assessment into the compliance analysis. Unforeseen by whom? Reasonably unforeseen, or subjectively unforeseen? And what are relevant circumstances—time off for vacation, budgetary limitations, the press of other work?

The ACLU of Iowa agreed that words like “difficulty” and “unforeseen circumstances” are subjective and therefore “provide too much discretion to the custodian of the records.” (Disclosure: Bleeding Heartland and I are among six plaintiffs in an open records lawsuit the ACLU filed against Governor Kim Reynolds last December.)

In its comment to the Iowa Public Information Board, the ACLU of Iowa wrote,

At the end of the day, events such as disasters, or even pandemics, while not predictable in terms of when they occur, are in fact predictable events in the sense that such conditions will, inevitably, arise from time to time. Custodians of records must have procedures in place to reconcile their obligations to produce records with predictable difficulties in doing so; a failure to do so creates a scenario in which predictable situations become a pretext for ‘impossibility,’ even when the agencies and offices have the capacity and the obligation to provide public records in even some form. […]

The public policy reasons for that are self-evident; it is in times of duress and emergency that the public’s access to understand and see what our government is doing is most important. In such times, access to public records – whether by individual citizens, educational groups, organizations like ours – and particularly by the free press – are of paramount public interest and can, and often do, become matters of life and death.

The ACLU suggested alternate wording that could apply to situations when it was impossible for a government body to provide prompt access.

Giudicessi observed that “it appears particularly untoward that an executive branch agency would seek to modify the Horsfield Materials factors” while the governor’s office has appeals pending with the Iowa Supreme Court regarding three open records lawsuits. (Two were filed by Utah attorney Suzette Rasmussen, and one is the case involving Bleeding Heartland.)

Rather than putting its thumb on the scales in favor of one litigant—one from the government no less—an agency should sit on the sidelines while the seven members of the Iowa Supreme Court consider the public records act issues presented and the scope of the Horsfield Materials factors. If an agency has a view to express concerning the pending cases and their challenges to delayed access to public records (in at least one case extending for more than a year), it could take a far better approach by filing a friend of the court brief rather than by changing the rules while the appeals are in progress.

MORE EXCUSES FOR “GOOD-FAITH, REASONABLE DELAY”?

Giudicessi and the Iowa Freedom of Information Council flagged another problem. Iowa Code Chapter 22.8(4) (a) through (d) spell out four circumstances that can justify a “good-faith, reasonable delay” in providing access to a public record. But the Iowa Public Information Board’s draft administrative rules state, “the lawful custodian may engage in a good-faith reasonable delay, including for purposes of […]” before listing those four circumstances.

Giudicessi wrote,

Through addition of the italicized language, however, the proposed rule mistakenly implies that grounds for delay may exist beyond those four possibilities specified in the language that follows in subparts (1)-(4). […]

Any indication that the grounds listed in Iowa Code § 22.8(4) are non-exclusive, or that the reasons for delay permitted by the rule include, but are not limited to, the four specified in the statute will result in confusion, if not alteration of the law.

Administrative rules are supposed to clarify how statutory provisions are implemented. They are not supposed to change the law itself.

WHAT’S MISSING FROM THE DRAFT RULES

The ACLU of Iowa suggested several additions to the administrative rules. For instance, some language would require custodians to “ask the requester which piece or pieces to fulfill first, and shall provide the requestor with any segments of the request that can be released separately” if one part of a request could not be provided promptly.

Another passage would clarify that in cases involving a “good-faith, reasonable delay,” the records keeper “shall provide the requestor in writing an estimate of the reasonable amount of time to satisfy the request, and shall itemize any segments of the record that may or will be subject to a lengthy or multistep process as provided by law or rule.”

The ACLU also noted that Governor Kim Reynolds recently signed a law (Senate File 2322) “relating to the assessment of fees when a person requests examination and copying of public records.”

The new law addresses timeliness in the context of certain requests and fees. Governing bodies are required to make every reasonable effort to provide records at no cost other than photocopying fees, for requests that takes less than thirty minutes to produce. We strongly recommend the Board incorporate the provisions of this new law into the adopted rules.

I expressed concern over the Iowa Public Information Board’s intention to rescind a subrule allowing it to “order administrative resolution of a matter by directing that a person take specified remedial action.” Without that leverage, I am concerned the board’s staff will not be able to persuade government entities to agree to reasonable informal resolutions, which sometimes resolve open records complaints.

CONTRARY TO THE “SPIRIT AND INTENT” OF THE OPEN RECORDS LAW

Herb Strentz submitted his own comments to the Iowa Public Information Board in support of the feedback Giudicessi and I had offered. He was “deeply involved” with revisions to the public records law in 1984, having served on a relevant governor’s task force and as the founding executive secretary of the Iowa Freedom of Information Council.

Strentz reminded the board members of the “spirit and intent” of Iowa’s sunshine laws: “access to government records and meetings should be broadly construed and exceptions to that access be narrowly drawn.”

In fact, one part of the open records law stipulates, “free and open examination of public records is generally in the public interest even though such examination may cause inconvenience or embarrassment to public officials or others.”

Strentz argued that “changes under consideration by the Iowa Public Information Board are contrary to the historic need for and support of public access to government information.” Moreover, while some “public agencies and officials abuse their discretion” by expanding the scope of confidentiality when dealing with records requests, portions of these administrative rules “invite, probably guarantee, still more abuse of the public’s right to know about access to information and decisions that affect their lives.”

Appendix 1: Full text of comments Laura Belin submitted to the Iowa Public Information Board on July 11, 2022

To the members of the Iowa Public Information Board:

I am writing about the proposed administrative rule ARC # 6306C, to share my perspective as a reporter who has submitted dozens of public records requests to state or local government entities in Iowa.

1. The board proposes to rescind subrule 2.1(6), which allows the Iowa Public Information Board to “order administrative resolution of a matter by directing that a person take specified remedial action.”

I am concerned that removing this authority will make it less likely that any government entity will agree to reasonable informal resolutions that Iowa Public Information Board staff recommend in order to resolve open records complaints.

2. I appreciate the proposed rule’s clear statement that “Government bodies shall give a high priority to fulfilling requests for copies of public records.”

3. I also appreciate the requirement for government bodies to acknowledge receipt of public records requests. Certain government entities have sometimes ignored requests, rather than expressly refusing to provide records.

4. I appreciate the proposed wording that requires acknowledgements to “include the name and contact information of the person responsible for processing the public records request.”

Some state government entities funnel open records requests through email accounts that don’t include any state employee’s name or contact information, which can make it difficult to follow up on outstanding requests.

5. I appreciate the proposed language stating that “a necessary delay in providing access to one or more records shall not delay providing access to the balance of the records requested.” I have sometimes experienced long delays in obtaining public records, even though most of the material requested was readily available.

6. I have serious concerns about the following proposed subsection:

In assessing whether a government body provided access to records promptly, or as soon as feasible, the following factors may be considered: […]

11.6(4) The existence of unforeseen circumstances that reasonably interfered with the lawful custodian’s ability to search for or retrieve the requested records.

I do not see any part of Iowa Code Chapter 22 that authorizes this “unforeseen circumstances” language. The General Assembly regularly amends portions of Iowa Code Chapter 22 and could have added such language, but has not done so.

Based on my firsthand experience, I fear that government entities could seize on any number of pretexts to justify an unreasonable delay in retrieving records. The obvious example of the COVID-19 pandemic comes to mind, but agencies could also claim a budget cut, or some employee taking parental or medical leave, was an “unforeseen circumstance” making it impossible to search for requested records for months on end.

Thank you for your consideration as you work on the proposed rule ARC #6360C.

Yours,

Laura Belin

Appendix 2: Full text of comments Herb Strentz submitted on July 11, 2022

To the members of the Iowa Public Information Board:

I write in strong support of the comments submitted by Laura Belin and Michael Giudicessi regarding proposed administrative rule ARC # 6306C.

When dean of the School of Journalism at Drake University, I served as executive secretary of the Iowa Freedom of Information Council from its founding in 1976 to 2000. And I was a cochair of the Citizens Privacy Task Force, July 1978 to January 1980, appointed by Gov. Robert D. Ray to “Study state statutes, rules and proposed legislation relating to privacy and confidentiality” with regard to citizens’ rights to access public records and yet consider the needs to protect the privacy rights of citizens identified in those records.

In those capacities I was deeply involved in the revision of the open meetings law in 1978 and the public records law in 1984.

The comments by Ms. Belin and Mr. Giudicessi are consistent with the spirit and intent of those laws that access to government records and meetings should be broadly construed and exceptions to that access be narrowly drawn.

Legislators granted what they saw as limited discretion to government agencies to restrict access as expressed in those laws.

With regard to access to records, 22.8(3) declares, “free and open examination of public records is generally in the public interest even though such examination may cause inconvenience or embarrassment to public officials and others.”

The comments by Ms. Belin and Mr. Giudicessi point out where the changes under consideration by the Iowa Public Information Board are contrary to the historic need for and support of public access to government information.

Some public agencies and officials abuse their discretion in markedly expanding what was supposed to be the limited provision to confidentiality the legislature intended.

Changes contemplated by the IPIB, as Ms. Belin and Mr. Giudicessi point out, invite, probably guarantee, still more abuse of the public’s right to know about access to information and decisions that affect their lives.

Herb Strentz, Urbandale, Iowa

Top image: Photo of public records Laura Belin received from the Iowa Department of Management in late April 2022, in response to a request submitted in early March 2022.

3 Comments

An Open Contradiction

At the risk of sounding hopelessly Old School, the notion that a state agency can enforce open meetings and records is an exercise in contradiction. Government bodies, no matter what their function, are inherently protective of established precedents and customs. Only an aggressive media, which is increasingly rare in today’s financial and political environment, can enforce open government. A bureaucrat will be far more fearful of revelation on page on or at the top of the 6 p.m. news than an appeal to another bureaucrat.

Dan Piller Fri 15 Jul 9:40 AM

I think a board could be created

that aggressively enforced the open records and open meetings laws. But this board (entirely appointed by the governor, with no jurisdiction over the governor’s office, and only 2-3 “media representatives”) is never going to operate from a presumption of openness that the law requires.

Laura Belin Sat 16 Jul 12:00 AM

Proposal is inadequate

I used to respond to public records requests at a small agency. My concern was always the lack of specificity in the guidelines for responding. I felt that more people would benefit from a hard deadline, like 10 business days to respond, than more aspirational goals, like “promptly”. These proposed rules seem to move in the direction of fuzzy aspirational language, especially the “unforeseen circumstances”.

I recognize that agencies may not be fully staffed and able to make responding to requests their highest priority, but this proposal doesn’t do much for encouraging agencies to rank their priorities so that requests receive a prompt response. There are no hard penalties, for example. A person responsible for responding doesn’t have a lot of ammunition if a superior is not committed to quick full responses. It would be nice to be able to point to rules that required a response within so many days, specific penalties for not doing so, and even specific requirements that any redactions have to be supported by specific statutory provisions related to confidentiality. I don’t feel like this board is committed to purpose of the open records statute, and there are certainly people in government who aren’t either. I suspect we’ll never see strong, clear rules come out of this board.

x Mon 18 Jul 2:29 PM