This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

The year 1848 was momentous in the life of young Iowa pioneer Alexander Clark.

On June 21, he and Benjamin Mathews purchased property on East 7th Street where their church would be built the following year. The Muscatine congregation became known as “the oldest colored church in Iowa.” (I’ll say more about the church in future columns.)

History reveals two other events of 1848: Alexander’s marriage to Catherine Griffin, and around the same time, his role—or maybe theirs—in a drama his eulogist will extoll in 1892, calling him “one of the Underground Railroad engineers and conductors, whose field was the South, whose depot was the North, and whose freight was human souls.”

Cade, 19, and Alex, 22, as they were known, married in Iowa City on October 8 or 9 (Sunday or Monday). That’s where they first became acquainted, when she had been “employed in the home of E.C. Lyon, Esq.” I rely on her obituary.

Pursuing the clue, I learned that Ethiel Child Lyon (1814-1884) was a land developer and one of the first regents of the state university, serving 1847-1859. An 1846 directory shows him as proprietor of a mercantile establishment selling dry goods and groceries.

I learned nothing of the conditions of Cade’s employment. However, I discovered one of E.C. Lyon’s daughters married to a son of David Warfield who, with two cousins, had brought Muscatine’s original Black residents from Maryland in 1837. The Warfields set up a dam and sawmill on Mad Creek.

Historian Robert Dykstra:

The Mathewses had been slaves belonging to the Warfield family back in Maryland, but had been freed, probably with the understanding that they become the cousins’ work force out on the labor-scarce frontier. In 1840 young Warfield’s interracial household included four black couples and their children, amounting to fifteen persons in all.

Catherine’s obituary yields another connection. She “embraced religion and connected herself with the M.E. [Methodist Episcopal] Church at the age of 13 years, and upon…coming to Iowa City [from Virginia by way of Linn County, Iowa], was taken into the church by letter under the Rev. John Harris.”

It turns out Pastor Harris served in Iowa City in 1846, the year Iowa became a state, then moved on to Muscatine for the next two years—a timeline coinciding with courtship and marriage for Cade and Alex. Perhaps he presided at their exchange of vows.

He also might have attended the third annual convention of the Iowa Anti-Slavery Society held at Iowa City in December 1845. “The abolitionists met in the basement of the town’s Methodist chapel,” reports Dykstra, and they adopted resolutions against Iowa’s onerous “Black code” created by the first territorial legislature.

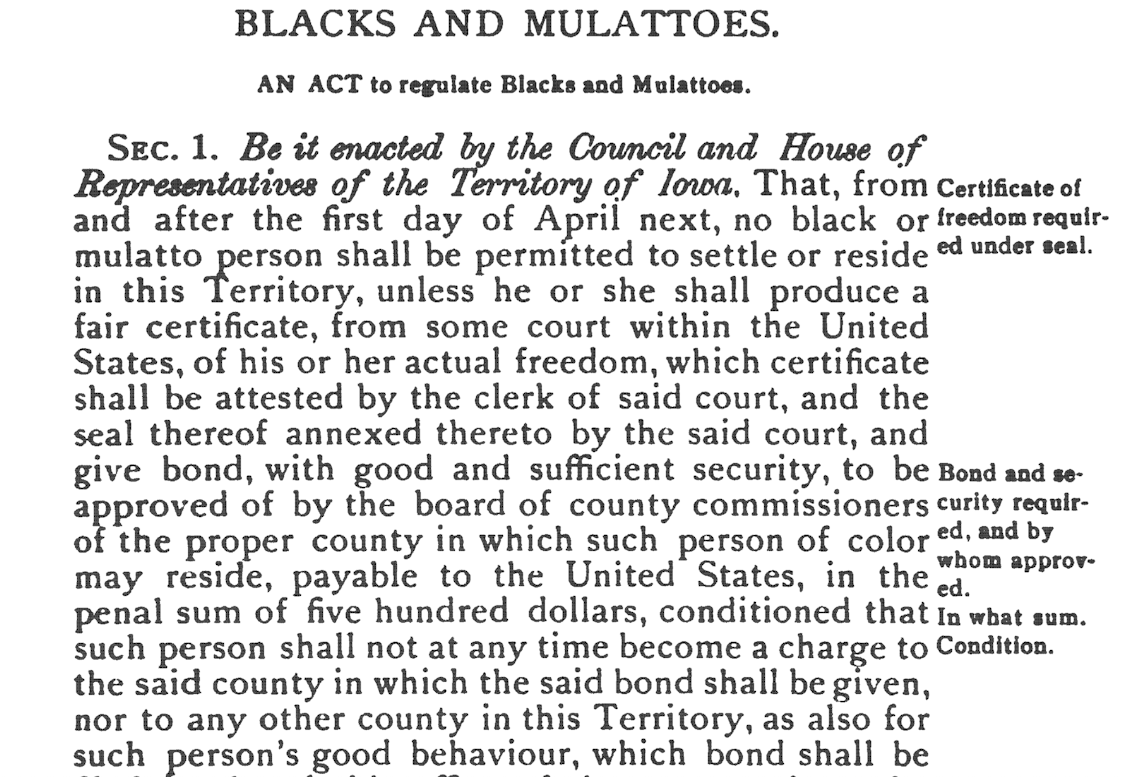

The 1839 Act to Regulate Blacks and Mulattoes required a certficate of freedom and $500 bond against becoming a public burden; “also for such person’s good behavior.”

Over the next decade, lawmakers removed rights and added restrictions, and in 1851 would fully prohibit African-American immigration.

“[W]hite Iowans need only look across their southern border, where lived some 115,000 slaves,” writes Dykstra. “A ceaseless theme of Iowa’s conservative editors and polticians…was that the immediate consequence of legislating racial equality in any form would be an overwhelming inrush from Missouri’s nearby ‘black belt.’”

The 1840 census shows 25 of Iowa’s 188 Black residents resided in Muscatine. By 1850 the city counted 62 of the 333 statewide total.

Alexander’s barber shop became a thriving business. He purchased land and harvested timber to fuel steamboats plying the Mississippi River, surely creating work and income for other residents. He invested profits in real estate. County records reportedly reveal that in years ahead he became one of the county’s larger taxpayers. (I intend to look into those records someday.)

I don’t know where the Clarks made their first home together, but in 1849 they bought a house at West 3rd and Chestnut where they would raise children and stay until Catherine’s death in 1879. Dr. D.P. Johnson came to town in 1848 and moved into a house across the street from the Clarks a few years later. He conducted his medical practice there, and the families were neighbors for the rest of their lives.

Right around the time of their wedding, whether at the house they would buy or somewhere else, the couple sheltered a young man fleeing a slave catcher from Missouri. Thus began an encounter with the legal system which would eventually lead father and son to fame as the first Black lawyers in Iowa.

“The Negro Case,” as the adventure was described in the Bloomington Herald (Octover 18, 1848), would soon connect the Clarks with another couple, the O’Connors, Henry and Sarah, who arrived in 1850. Henry would become Attorney General of Iowa and a central figure in ending the Black codes.

Next time: The story of Jim as told by some who were there.

Top image: From “The Statute Laws of the Territory of Iowa” (1839).