This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

There’s no marker at the 1850 Henry O’Connor house atop West Hill on Cherry Street.

From reading Iowa history and the Alexander Clark story, there’s no doubt in my mind that Iowans owe much to the Dublin-born lawyer who’s been largely forgotten.

He arrived at age 29 in 1849 and joined the firm of David C. Cloud, the magistrate who had freed a fugitive slave in 1848. (“Freedom seeker” is today’s term.) O’Connor’s association with Clark may have started around that time. Surely by 1857 they were allies in the causes of abolition and equal rights.

Ten years later O’Connor would be one of Clark’s lawyers in a landmark school desegregation case—as well as Attorney General of Iowa. And both men were acclaimed as eloquent orators wherever they addressed crowds, often the same crowds. I’ll write about their teamwork in future columns.

From Clark’s entry in The United States Biographical Dictionary and Portrait Gallery of Eminent and Self-made Men (Iowa volume, 1878):

His father was born a slave, yet the son of his master, an Irishman, who emancipated both him and his mother, who was a mulatto. The mother of Alexander Clark, who still lives, at the age of seventy-one years, is a full-blooded African, consequently our subject is two-thirds African and one-third Irish.

The biographer credits Irish ancestry “in a great measure” for

the genius and brilliancy which so much adorn his character, for it must not be supposed that because the Irish element in his composition is comparatively small that its influence in the formation of his character is not very considerable. Scientific men are familiar with the fact that the potency rather than the quantity of an ingredient in any mixture determines the general effect; and we have no doubt that to the circumstance alluded to is mainly due the existence of those elements of character which have led to the success to which Mr. Clark has attained.

May we not, in our more enlightened time, dismiss this ramble as 19th century eugenics nonsense? Sure and begorra, I say, in toast to Irish-American Heritage Month. Certainly we should. Still, I’m sure the readers of the day took it as gospel, published in a volume so “durably and elegantly gotten up” with leather binding and gilt letters.

Reading on, we learn the children “Rebecca J., Susan V., and Alexander G., all inherit their father’s intellectual endowments, all severally graduates of the high school of Muscatine, and give promise of useful and honorable lives.”

And, whatever the veracity of the author, this is the book that gives us the fine engraving that became Clark’s best known portrait.

Traveling in Ireland in 2018 with Muscatine neighbors named Kelly, my wife and I visited the Museum of Country Life at Castlebar. We learned the National Land League founded there in 1879 was noted as a step toward freedom from English rule, having achieved some success in uniting tenant rights movements under a single organization.

Remembering about Irish independence in a Clark speech, I “connected dots” and found him addressing the state centennial convention of colored citizens held in Oskaloosa (January 4, 1876):

I am proud to pay homage…to the great party of progress which bears the name of Reform in England, in Ireland, Fenianism, in America the great Radical Republican party, which stood firm and uncompromising when treason and rebellion shook the nation as with the throes of an earthquake.

In 1881 the Journal reported the Muscatine branch of the Irish Land League holding meetings at Shamrock Hall and welcoming “all lovers of liberty and fair play.” The first meeting’s report lists 42 men who joined that night.

“During the enrollment, lest there should be some doubt about the admission of other than Irishmen, Alex. Clark, G.W. Van Horne and A.W. Lee were called upon for their names. Mr. Clark responded with an eloquent and characteristic speech in which he announced himself ever in favor of ‘liberty’ and expressed his hearty sympathy with the movement. He was loudly applauded.”

From the Columbus Junction Safeguard: “The antipathy generally supposed to exist between the Irish and the negroes seems to have been forgotten in Muscatine where Alexander Clark, the colored orator, made an eloquent speech at a meeting of the Land League and was elected one of the officers.”

Later, answering a request for signers to a call for a statewide meeting, “the names of President [Samuel] Sinnett, W.F. Brannan and Alex. Clark were chosen.” The call appeared in the Des Moines Register with 39 names, including the Muscatine three.

But the name of Muscatine’s most famous Irishman was missing. In 1872 Henry O’Connor had accepted President Ulysses S. Grant’s appointment and moved to the nation’s capital, where he would serve nearly fourteen years as Examiner of Claims under four secretaries of state.

He died at the Iowa Soldiers’ Home at Marshalltown in 1900.

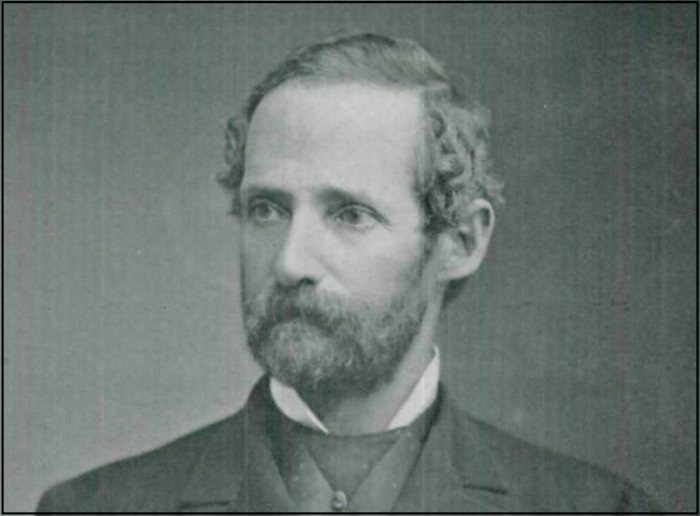

Top image: Henry O’Connor was Attorney General of Iowa from 1867 to 1872. Detail from Annals of Iowa, January 1, 1901.