This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

“Frontier Iowa’s most prominent black citizen.” That’s the first mention of Alexander Clark in the book I recommend to any adult serious about studying his life and times. Bright Radical Star: Black Freedom and White Supremacy on the Hawkeye Frontier, by Robert Dykstra (Harvard University Press 1993).

Iowa a “bright radical star”? Wow. Who said that?

General Ulysses Grant, presidential candidate, November 1868. If you don’t know the reference, I invite you to learn. I will look closer at the Iowa of 1868 in a future column.

As these little columns are expanding out of a one-time effort for Black History Month, I beg readers to notice that I am the farthest thing from an academically trained historian. “Local” or “community” historian is a label I reluctantly accept only when I can’t avoid it.

So please let me insist on amateur status, observing that I’ve learned just enough to realize how very little I know. In this regard, discovering Dykstra has been life changing. No exaggeration. His story-telling is a marvel; his grasp of big themes and tiny nuances, the methodology and the rigor and the relevance to social and political landscape today. Wow. If you care about how our settler forebears shaped the demography of present-day Iowa, find Dykstra.

March is Women’s History Month. We are able to learn so much about the males in the tale but so little of their mothers, wives, sisters, daughters. My study of Dykstra didn’t prepare me to wonder, and I confess I gave it little thought during my first years helping Kent Sissel with Alexander Clark Projects.

The second book I recommend for serious learners is by Leslie Schwalm at the University of Iowa. Emancipation’s Diaspora: Race and Reconstruction in the Upper Midwest (University of North Carolina Press 2009).

From the UI website: “Professor Schwalm is a historian of gender and race in the nineteenth-century U.S., and her research focuses on slavery, the Civil War, and emancipation. She holds a joint appointment with the Department of Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies and with History.”

I heard her speak at Muscatine’s Musser Public Library in February 2008. The announced topic: “Emancipating Iowa: Lincoln’s Proclamation and Black Freedom in the Upper Midwest.” I love listening to “real” historians. I love reading their books and articles. I went in ready to hear our Alexander Clark story lauded and my grasp of it affirmed. Sitting together, Kent and I were keen to learn. As always, we were ready to offer additions and corrections, too. (It’s what we do—what we still do today. Another of those stories for another time.)

Perhaps we felt ready for our hero’s minor role in the lecture’s broad sweep, but Schwalm’s female-centered treatment of the topic shut our mouths. What about the women, she asked? We can only conjecture because the historical record tells so little, she said.

From Emancipation’s Diaspora:

Born in the early 1820s in western Virginia, a slave of Jacob Ankrom, Catherine—or ‘Cade,’ as she was called by her owners—was given as a wedding present (along with hogs, sheep, cows, and bedding) to Ankrom’s daughter Rachel. Catherine would have been very young at the time, perhaps three years old, and she appears to have been one of three slaves held by Ankrom—the other two, adults, may have been her parents. When her new mistress married Patrick Cheadle, she moved to Morgan County, Ohio, and took the toddler Catherine with her, most likely severing Catherine’s own family ties. In Ohio, Catherine’s status is not evident from the historical record; the Ohio constitution outlawed slavery in 1803, but the state soon severely circumscribed African Americans with black laws, and as late as 1830 the federal census still recorded slaves (six in number) in the supposedly free state. The most suggestive piece of information we have about Catherine’s status is a manumission record that was not legally signed until after Catherine and the Cheadles had left Ohio. Catherine accompanied the couple when they migrated to lowa sometime before 1842, but it was not until 1851 that Patrick Cheadle drafted Catherine’s manumission papers, and it would be another six years before Rachel, his wife, would add her signature. By this time, Catherine had married, established her own household, and started a family in Muscatine; she had become politically active, joining with other African Americans in petitioning the state legislature to revoke Iowa’s black codes. The record of Catherine’s status is inconclusive, though she clearly sought documentation of her freedom—perhaps in the aftermath of her 1848 action to protect a fugitive slave from capture in Muscatine—and that documentation was given by her former mistress only reluctantly.”

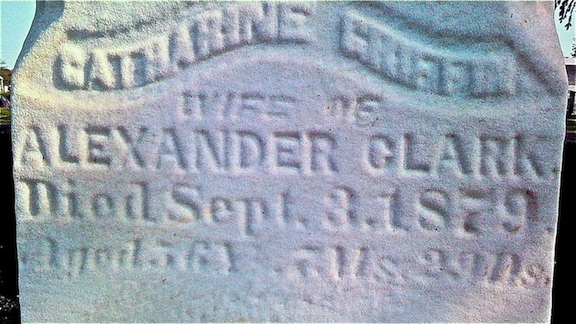

We finally meet husband Alexander 10 pages later. They married in Iowa City. She is listed among the founding members of Bethel A.M.E. in 1849. The Clark monument in Greenwood Cemetery bears her name.

Top image: Catharine Griffin Clark’s name on the family monument at Greenwood Cemetery, Muscatine. The “a” in Catharine appears in her obituary and on this stone; all other known documents show the “e” spelling.