This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

Early in the research for his Alexander Clark biography published in the Drake Law Review, retired Iowa State Supreme Court Justice Robert Allbee visited Muscatine to consult with Kent Sissel, the preservationist who has resided in Clark’s house since it was moved and saved from demolition in the late 1970s.

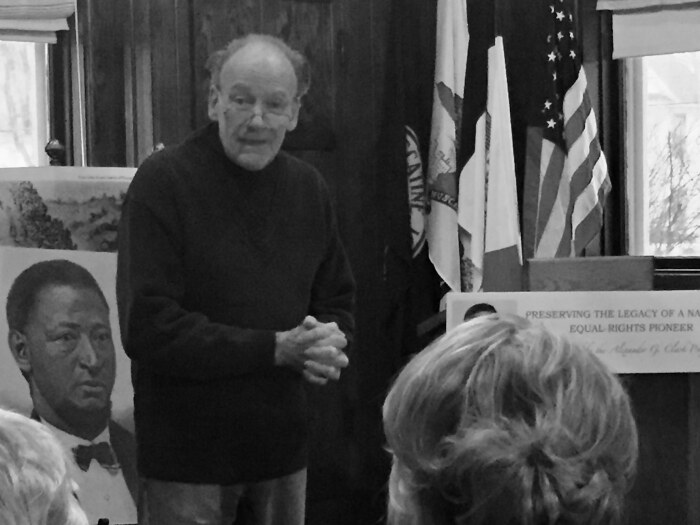

“I’ve spent the last 40 years, more or less, protecting the legacy of Alexander Clark,” Sissel told him in the hour-long conversation they recorded that day in 2018.

I met Kent in 1985 when he operated a bed and breakfast on one side of the historic double house. I’ve been learning the Clark story a bit at a time ever since. In 2005 I started paying attention in earnest, working on what Kent calls Alexander Clark Projects. We started a website. He supplied content; I worked on presenting it.

“History reveals itself over time,” he told me. And he still insists, to anyone who’s interested in recovering the lost history: “Connect the dots!”

As webmaster, I soon received a courteous message from the editor of The Christian Recorder, “The Official Newspaper of the A.M.E. Church,” seeking to reprint an article we had linked.

“Brother Clark,” began the inquiry. It was the first time someone suspected I might be related, maybe even a descendant of the great man. So I imagined. The editor didn’t ask, nor did I explain.

That wasn’t the last I’ve been asked about a family connection, nor the first time our project prompted me to explore my views on race and identity. I quickly grew used to the ambiguity and came to enjoy it.

“A brother by another mother!” declared Professor Adrien Wing, the main speaker at the 2019 dedication of the Alexander Clark Room atop Muscatine’s strikingly attractive Merrill Hotel and Conference Center. I’ve claimed the label ever since, repeating the anecdote as opportunity arises.

The Muscatine Journal, reporting the event: “Views from the room include his 1878 home and the Clark House apartments built on the home’s original site.” The hotel website croons: “Gather your wedding party in our Clark room, a unique venue offering spectacular river views.”

Kent is quick to point out that he’s not the only keeper of the legacy; that he took over from Bette Veerhusen and Aldeen Davis who did so much to revive lost history. He mentions others: Marilyn Bekker, Deba Foxley, Marilyn Jackson, Burtine Motley, Betty Stanley, Berniece Williams.

So many women, interestingly. Women haven’t taken all the important roles in the effort, but it’s fitting to note them in Women’s History Month, having stretched my tale on past the end of Black History Month—like Scheherazade, I’m thinking. But I’m old, so maybe more like I’m binge-watching episode after episode until a cliffhanger ends the season.

I wrote to Editor Hotle: “I’ve started pacing myself and imagining how this story unfolds.” He said it’s going well so far.

“Lyn” Jackson in The Iowan magazine, Spring 1975: “Clark had voiced the hope that events of his life would be an inspiration to young people, especially those of his own race, to set worthwhile goals and achieve them in spite of obstacles. Muscatine hopes that this inspiration may be extended to present-day and future youth by the building that will bear Clark’s name. Plaques and displays in public areas of the building will outline the events and accomplishments that marked the life of Alexander Clark.”

Muscatine Journal (March 5, 1990): “Speaking to the more than 200 students of high school and college age from around the nation who were attending the 13th annual Minority Pre-Law Conference at the [University of Iowa], Motley said ‘You are on the path of following in the footsteps of Alexander Clark. Don’t be afraid to knock on any door…this is our opportunity to make a difference for all people.’”

Last month a TV interviewer asked why I am passionate about the Clarks’ story. No credit to me, I said. My parents exposed me to important issues early. They modeled interracial friendship with the “Negro” couple who sat near our pew at Marion Street Methodist in Boone. My parents took me, at age 8, to hear the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speak in Ames. I wish I still had my 1958 NAACP junior membership card.

Passing my seventh decade I’m as sure as ever that how we are raised matters tremendously. This story isn’t about me, but I’m owning my part and taking a chance to do some good—in first person, active voice—starting from Black history and wending and weaving my way into our common stories going forward. Connecting dots!

Top image: Kent Sissel speaking about Alexander Clark in February 2019.