This column by Daniel G. Clark first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

Muscatine’s first Alexander Clark Day was proclaimed by Mayor Walter Conway in 1958. Sixty years later the city council voted unanimously to honor the famous resident’s birthday in perpetuity.

August 1890: “Alexander Clark, the new minister to Liberia, and who is known throughout the country as the colored orator of the West, was born in Washington county, Penn., February 25, 1826.”

So begins the short biography published nationwide and surely authorized by Clark himself. In 1872 the media-savvy publisher-lawyer-churchman had turned down President Ulysses S. Grant’s offer of appointment to Haiti, reportedly because the job didn’t pay enough.

From the Des Moines Register (August 1882): “Among the members of the State convention to-day will be Mr. Alexander Clark, of Muscatine, the noted colored orator and politician, who is also very prominent in York Masonry. Mr. Clark was the first colored man put on the political stump in the United States by any party…. He has done much for his race, and much for the Republican party, and it is to be hoped that some day a Republican administration will recognize him, his worth and his service, by appointing him to some responsible and honorable position. He would make a capital minister to Liberia.”

President Benjamin Harrison did appoint Clark to Liberia, soon after appointing Frederick Douglass to Haiti. Douglass—The Colored Orator—with no regional qualifier on his title.

Although Douglass was indisputably more famous, there was a long, friendly relationship. In an exchange of complimentary letters in 1888, they address one another as old friends. Clark says “near half a century” and calls Douglass “the greatest negro living on the earth.”

From the 1890 newspaper bio: “Mr. Clark was elected delegate from Iowa to the first national colored convention held in this country, which met at Rochester, N.Y., in 1853.”

It’s possible Clark and Douglass did meet in 1853, but there’s no other record that young Clark actually attended. We do know he was listed as sole Iowa agent for Douglass’s antislavery newspaper, The North Star, as early as 1850. And we do know the two men appeared together on various occasions including at least one Douglass speaking tour in Iowa.

Clark’s Liberia service ended abruptly. From the Chicago Tribune (July 20, 1891): “Memorial services were held yesterday afternoon for the late Alexander Clark, United States Minister to Liberia, who died May 31…. Mr. Clark was one of the most influential and well-known colored citizens of the United States, and during an eventful life of sixty-five years was actively engaged in the abolition movement, the ‘underground railroad,’ the rebellion, and since the war had been foremost in the endeavor to elevate the African race.”

Fast forward to Alexander Clark Day 1958 and the program organized by the Junior Mission of the African Methodist Episcopal congregation known as Bethel A.M.E.—the church Clark helped found in 1848. A special guest, Adaline Clark of Oskaloosa, presented the eulogy booklet published following her father-in-law’s interment at Greenwood Cemetery in 1892. It is now in the special collection at Musser Public Library.

In the mid-1970s the threatened demolition of Clark’s once-handsome 1878 brick house at West 3rd and Chestnut streets spurred a public rediscovery of the family’s story. The site had been chosen for a 10-story senior high-rise apartment, and federal funding was at stake.

Iowa’s Liberian connection shone again as Burtine Motley, a Black woman from Cedar Rapids, led a movement to save “the ambassador’s house.” Newspapers and the Iowan magazine revisited the 1868 Iowa Supreme Court ruling for which Alexander and daughter Susan are best remembered.

Finally the house was saved and moved up the street. The high-rise arose and got christened Clark House.

That story is told in a 2012 documentary film “Lost in History: Alexander Clark.” In the film, constitutional law historian Paul Finkelman says of the 1868 ruling: “It is the first successful school desegregation case in the history of the United States. That makes the Clark case extremely important.”

Finkelman was the keynote speaker at a “Clark 150” symposium at Drake University in 2018. “Alexander Clark is the greatest African American in American history that no one has ever heard of,” he said.

The City of Muscatine created the Alexander Clark Heritage District in 2010. Clark’s letter of appointment signed by President Harrison was acquired for the permanent collection of the Muscatine Art Center.

The State Historical Society of Iowa awarded a grant to the city’s Historic Preservation Commission for the purpose of nominating the historic residence for federal recognition as a national historic landmark, but the initiative bogged down and has been revived only recently.

The sticking point? It turns out the original nomination to the National Register of Historic Places (a 1976 U.S. Bicentennial project) established “state significance” only.

Now a case must be made for Alexander Clark’s national significance.

Daniel G. Clark is not related to Alex but is proud to claim him as “brother by another mother.”

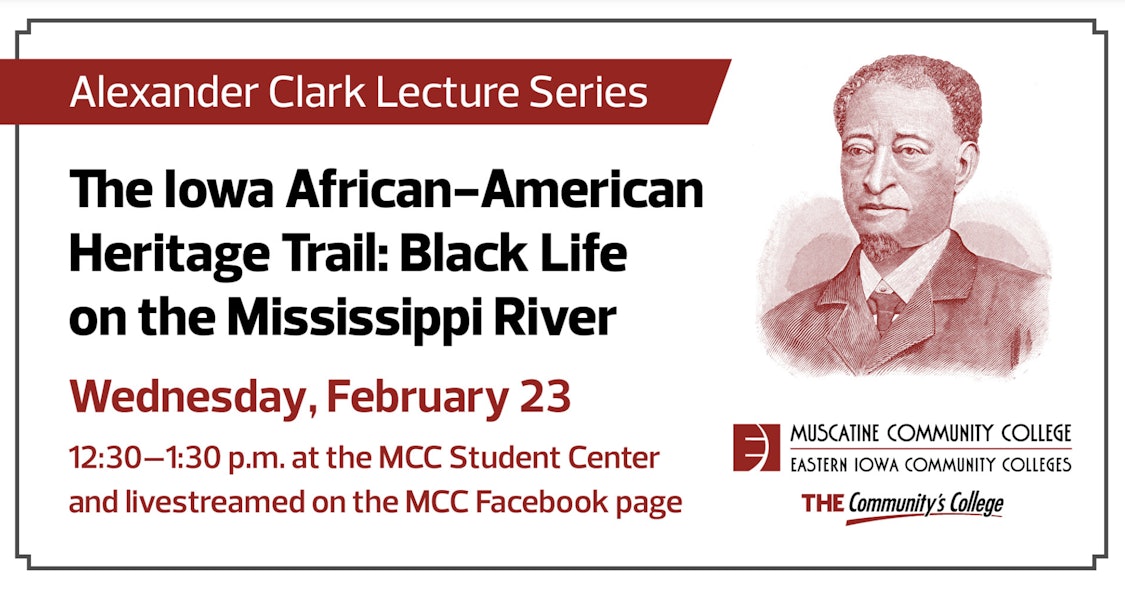

Editor’s note: The next Alexander Clark Lecture Series event at Muscatine Community Colllege is taking place on February 23.