PBS will premiere the movie “Storm Lake” on Monday, November 15 at 9:00 pm Central as part of the public network’s documentary series Independent Lens. If you miss it Monday night, you can catch it on IPTV World at 6:30 pm on November 17, 7:30 am on November 18, or 11:00 am on November 20.

I loved everything about the documentary film “Storm Lake.”

I loved seeing editor Art Cullen at work, getting “real uptight about deadlines,” and out in the community. (One local commented, “A lot of people disagree with him, but they sure read the paper.”)

I loved watching photographer and feature writer Dolores Cullen hustle for scoops on the “happy beat,” like Emmanuel Trujillo’s success on the show Tengo Talento Mucho Talento, a Spanish-language singing competition.

I loved watching founder and publisher John Cullen reconcile accounts and deliver papers to gas stations and restaurants.

I loved watching sales and circulation manager Whitney Robinson pitch ads to locally-owned businesses–a job that (amazingly) “got more difficult” after Art won the Pulitzer Prize, because some conservative locals weren’t happy to see a liberal voice honored.

And I loved watching lead reporter Tom Cullen take on all kinds of political stories, from interviewing a city council candidate in Alta (population 2,087) to asking Senator Chuck Grassley and presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg about immigration to writing up the massive Latino turnout for Bernie Sanders on Iowa caucus night.

But nothing impressed me more than the film’s final fifteen minutes, when directors Jerry Risius and Beth Levison turned their attention to how the Storm Lake Times dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic.

The newspaper was “squeaking by,” managing to keep ten employees on the payroll in part because John donated his time after going on Social Security. Then their ad sales “fell off a cliff,” dropping 50 percent during the first month after COVID arrived in Iowa.

Looking shell-shocked over Zoom, Art described the “very stressful” situation. They sat locked in their homes, “thinking we’re losing money, and there ain’t a goddamn thing you can do about.” He and John tried to figure out how to save the newspaper without going deeply into debt. They seriously discussed walking away from the business and selling the building to pay their debts. Eventually, Art set up a GoFundMe page to keep the Times solvent.

Meanwhile, the Cullens reported the hell out of this story. They highlighted the near-total absence of testing until mid-May, and the lack of information about COVID cases at Tyson. Tom got the runaround from corporate PR, while staff at the Iowa Department of Public Health and governor’s office ignored all of his emails.

But Tom persevered. He was first to report locally on the dramatic increase in confirmed cases, mostly linked to meatpacking. He reported exclusively on records showing that Tyson employees “were pushed to get back to work after being in hospital,” and that the state put a Test Iowa site in Storm Lake “eight weeks after the first reported case of the virus here.”

Dolores wrote obituaries for some of the first locals to succumb.

Art told the filmmakers that forcing workers (some of whom feared deportation) into “a potentially deadly workplace without testing” was a form of racism. That message came through loud and clear in his editorials. He warned in late April 2020 that the state was “Winging it with workers’ lives.” A month later, he wrote of the “fog of uncertainty and confusion” enveloping Buena Vista County.

Ten weeks after Gov. Reynolds told us to stay home, except for critical employees like meatpacking workers, we still don’t know actually how many people have tested positive in a community with more than 3,000 food processing employees. Nine days after full-scale testing started, as of Monday we had no idea how many total cases there were. We heard reports from doctors that the pace was quickening at the hospital. The hospital said that this is “real” but offered little more information. Is Sioux City full? Where do the seriously ill go? Why are helicopters flying out of Storm Lake?

What is going on?

We don’t know. It is outrageous. It is stunning that in this day and age, more than two months into this pandemic, we do not know how many people are stricken. We have half a picture. […]

Iowa should not be so desperate as to depend on Tyson for half our testing. The state should have done it, on time. We do not know when full results will be compiled and released, if ever.

Early in the movie, Art explained the newspaper’s approach to story selection: “If it didn’t happen in Buena Vista County, it didn’t happen.”

Many days, what happens in that county has little relevance to the wider world. But when COVID-19 hit, meatpacking towns were among the most important places to cover.

Art described Storm Lake as the “epicenter” of the pandemic in Iowa. To this day, Buena Vista has by far the highest per capita COVID-19 case rate of Iowa’s 99 counties. It’s in the top 20 counties nationally on that metric. Nearly 30 percent of residents have tested positive for the virus.

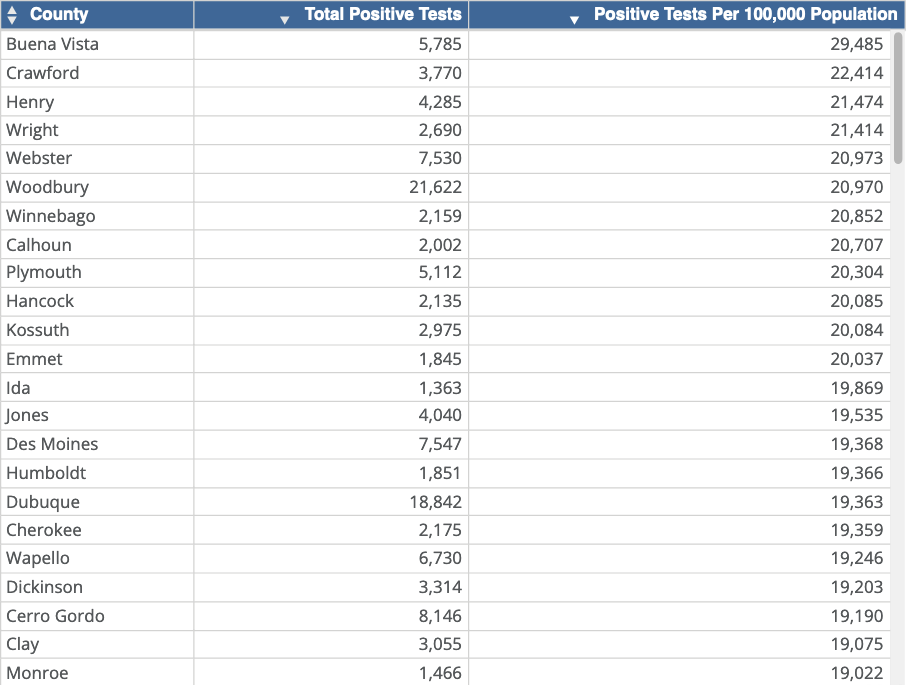

This table, which I pulled from Iowa’s official coronavirus website, shows that most of the hardest-hit counties have large workforces employed at pork or beef processing facilities in places like Denison (Crawford County), Mount Pleasant (Henry County), Eagle Grove (Wright County), or Sioux City (Woodbury County). Even in that company, Buena Vista is an outlier.

Unlike others who have reviewed “Storm Lake,” I haven’t worked in community journalism, or for any newspaper. Nevertheless, I could relate to the sense of urgency the Cullens conveyed about reporting on the pandemic. All over the world, journalists reinvented themselves as public health reporters overnight. But few of us covered any community as central to the pandemic as Storm Lake.

Iowans are fortunate that one of the best small newsrooms in the Midwest was in the right place at the right time and committed to this story, even as their backs were against the wall financially.

I’m proud to subscribe to the Storm Lake Times and to other small newspapers that produced outstanding original reporting about COVID-19 (the Iowa Falls Times Citizen and the Carroll Times Herald). You should watch “Storm Lake” on Iowa PBS this week, and if you have the means, consider subscribing to one or more community publications.

There’s only one thing I would change about the film. It never mentions the existence of another newspaper in Storm Lake. Longtime investigative reporter and journalism teacher John Dinges asked the filmmakers about the omission after a screening we attended in Okoboji in September. Director and producer Beth Levison said they reached out to the Storm Lake Pilot-Tribune several times and never heard back. They decided to keep the narrative focused on the Times.

During the same panel discussion, director and director of photography Jerry Risius (who grew up near Buffalo Center, Iowa) talked about the extremely difficult cuts editors needed to make to keep the film at a suitable length for the PBS documentary series. Although I can understand the time constraints, I would have liked to hear how this town keeps two newspapers in business, and what (other than Pulitzer Prize-winning editorials) distinguishes the two publications.

Top image, from left: Jerry Risius (director and director of photography), Beth Levison (director and producer), moderator Kyle Munson, Storm Lake Times editor Art Cullen, Storm Lake Times publisher John Cullen. Photo by Jan Myers following a screening of “Storm Lake” in Okoboji on September 20, 2021.