State officials deployed “strike teams” involving the Iowa National Guard to more businesses last year than previously acknowledged.

Records the Iowa Department of Public Health (IDPH) released on April 26 show seventeen workplaces received COVID-19 testing assistance through a strike team. The agency had stated in January that only ten workplaces (operated by nine companies) had strike team visits. Several newly-disclosed events benefited businesses linked to Governor Kim Reynolds’ major campaign donors.

Iowa used the strike teams mostly during the spring of 2020, when COVID-19 testing supplies were scarce. However, a strike team was sent to Iowa Select Farms administrative headquarters in mid-July, more than five weeks after the state had stopped providing testing help to other business. That company’s owners are Reynolds’ largest campaign contributors.

The governor asserted at a January news conference that the state had facilitated coronavirus testing for more than 60 companies, saying no firm was denied assistance. The newly-released records show nineteen businesses received testing kits from the state, and another nineteen were directed to a nearby Test Iowa site where their employees could schedule appointments.

The public health department’s spokesperson Sarah Ekstrand has not explained why she provided incomplete information about the strike team program in January. Nor has she clarified what criteria state officials used to determine which companies received which kind of testing assistance.

The governor’s spokesperson Pat Garrett did not respond to any of Bleeding Heartland’s emails on this subject. Reynolds walked away when I tried to ask her about the strike team decisions at a media gaggle on April 28.

AN INCOMPLETE PICTURE

I first requested information about the strike team program last June, but IDPH communications staffer Amy McCoy never answered any questions about where the state had sent the National Guard or how companies were selected for that assistance. Staff for the Guard referred inquiries to the public health department.

While researching the governor’s intervention on behalf of the GMT Corporation in Waverly, I tried again to ascertain the scope of the strike team program. In late December, I asked Ekstrand (who had recently replaced McCoy) for lists of food processing facilities and manufacturers not connected to the food system that received strike team assistance, with the name of the company, city, and date of each visit.

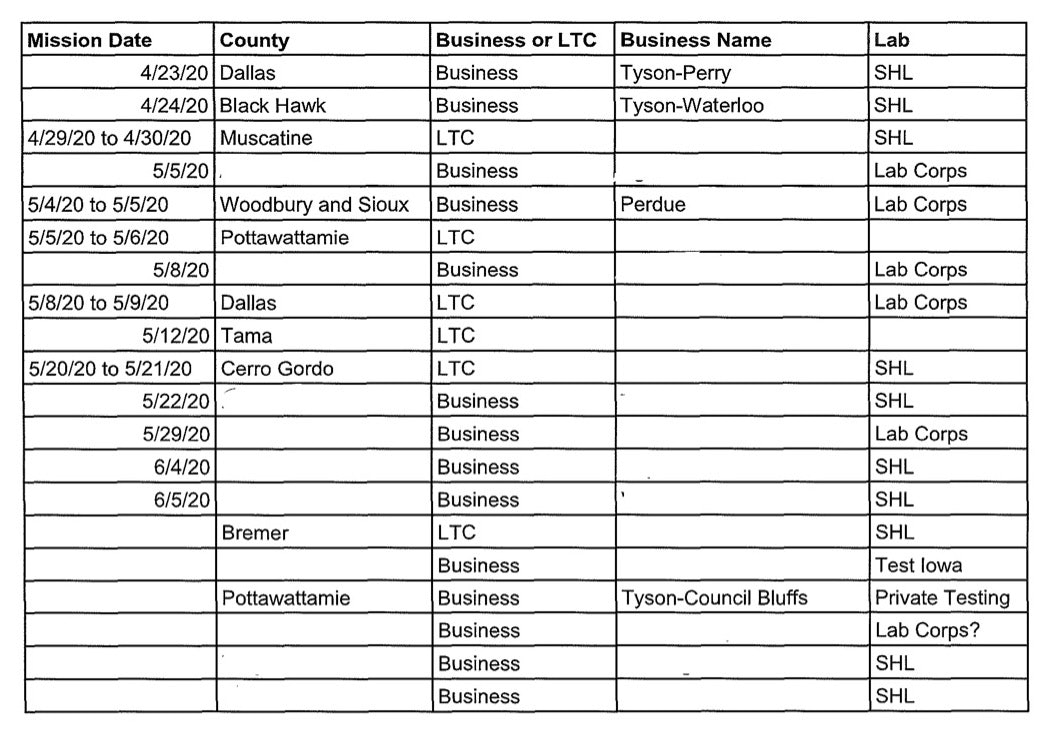

Ekstrand told me on January 6, “I think we are getting close to being able to issue the records request that will answer most of these questions.” She eventually provided this “redacted version of the strike team calendar” on January 12. “LTC” refers to counties where strike teams tested employees of long-term care facilities. A few meatpacking plants were listed, where media had already reported on the testing. The IDPH withheld other companies’ names, citing an Iowa Code provision on disease reporting.

Before publishing about the strike team visit to the GMT Corporation, I asked Ekstrand five times to clarify whether this document was a complete list of Iowa strike team visits. She explained on January 20 that the business listings with no dates didn’t get a strike team. Rather, they “secured their own testing either through local public health or a private testing group,” so “no state staff or assets” were sent to those companies.

That left nine businesses visited by strike teams (Perdue employees were tested at two facilities) and six counties where strike teams tested nursing home workers. “Please confirm that this list represents all strike team visits involving IDPH and Iowa National Guard personnel,” I emailed on January 20. Ekstrand checked with the “team” and eventually informed me on January 25 that other than an incorrect date for long-term care testing in Tama County, “The rest of the list, as well as the subsequent updates I shared are valid.”

Not quite.

NEWS OF A “RAPID-RESPONSE TEAM” EMERGES

Although the IDPH redacted GMT’s name, I had confirmed through other public records and an interview with GMT’s top executive that it was the company receiving a strike team visit on May 22, 2020. I reported on January 24 that the state green-lighted a strike team for the Waverly-based machine parts manufacturer after someone from Bruce Rastetter’s Summit Ag company “contacted the governor directly.” GMT staff got Summit Ag involved after learning they “would most likely be denied” testing assistance from the state, since they had only one confirmed COVID-19 case.

Citing emails Bleeding Heartland published, State Auditor Rob Sand announced on January 26 that his office would investigate the use of strike teams.

The next day, Associated Press reporters David Pitt and Ryan Foley revealed that the IDPH had coordinated COVID-19 testing for 32 people on July 13, 2020 “outside the West Des Moines office that houses the administrative headquarters of Iowa Select Farms and its charity.” The company’s owners Jeff and Deb Hansen have donated just under $300,000 to Reynolds’ campaign committee since 2016 (see here and here). From the AP story:

The testing occurred at an office used by white-collar employees of the company and the Hansens’ foundation. The governor has worked closely with both in the past.

Company spokeswoman Jen Sorenson said Iowa Select reached out to the governor’s office seeking help after “a number of individuals were found to be potentially exposed to a positive employee.” She said the governor’s office referred the company to the public health department, which determined a rapid-response state team was the appropriate way to provide testing.

I immediately sought clarification from Ekstrand: what was this “rapid-response state team,” and did it involve Iowa National Guard personnel? Were “rapid-response state teams” sent to other white-collar office settings? If so, on what basis did IDPH determine which companies would be prioritized for testing?

Why would the state dispatch anyone to a white-collar office for COVID-19 testing? Couldn’t most of those people be working from home? And couldn’t Iowa Select Farms shoulder the cost of testing 32 employees?

Additionally, wasn’t testing widely available through Test Iowa by July? I thought the IDPH was focused on surveillance testing in congregate settings or at crowded manufacturing workplaces.

At a televised news conference on January 27, Reynolds denied showing favoritism to any companies linked to campaign donors. She didn’t specifically address COVID-19 testing for GMT or Iowa Select Farms but said the state had helped more than 60 businesses and hadn’t turned down any company requesting testing assistance. The governor also emphasized the need to keep food processing plants from shutting down “so that we could keep food on the shelves and we could keep families fed.” However, GMT is not part of the food system, and no pork is processed at Iowa Select Farms’ administrative headquarters.

One week after AP’s article appeared, I hadn’t heard back from Ekstrand, so I emailed on February 3:

Officials have indicated that about 60 companies received some kind of COVID-19 testing assistance from the state last year. Based on information you have previously sent, my understanding is that nine companies received a “strike team” visit involving Iowa National Guard personnel. Please confirm that is still accurate.

I asked Ekstrand for a “list of instances when the state sent COVID-19 testing kits to Iowa-based companies during calendar year 2020, with dates,” and a “list of instances when the state sent rapid response teams with not only the testing kits, but the personnel to administer the COVID-19 tests at Iowa workplaces,” also with dates.

She replied the same day, “I am working on documentation that will include the information you’re asking about, and hoping to have it before the end of the week.”

More than a month later, I’d received nothing, so circled back again on March 12. No reply, so I asked again on March 23. Ekstrand apologized for the delay and promised to provide the information by the end of the week. That Friday, she said she would have it “early next week.” Acknowledging that message, I wrote, “Please also let me know if you have any additional information concerning the strike teams, beyond what you sent me in January.” Two months had passed since the Associated Press scoop, yet IDPH had not mentioned the “rapid-response team” sent to Iowa Select Farms headquarters was in fact a strike team.

By April, I suspected IDPH was ignoring my inquiries to avoid admitting Iowa Select Farms received preferential treatment. Was that company the only one to receive state-funded drive-through testing service?

Ekstrand told me on April 12 she was working on the request. Ten days later, I had received nothing, so I tried again.

I’m not asking for anything complicated. I want to know how many companies received COVID-19 testing kits from the state (and on what dates), and how many companies received not just testing kits but also a “rapid response” team to conduct COVID-19 testing at their workplaces (and on what dates).

Please also confirm that IDPH has not revised information previously provided regarding nine companies that received “strike team” visits involving the Iowa National Guard, on April 23 (Tyson Perry), April 24 (Tyson Waterloo), May 5 (media reports indicated that was Agristar), May 4 and 5 (Perdue), May 8, May 22 (media reports indicated that was GMT), May 29, June 4, and June 5.

On April 22, Ekstrand sent me what she called “the most comprehensive record of companies that the state provided COVID-19 testing support for in 2020.” She added, “Our team provided responsive support to each company that asked for assistance with testing, and no company was denied assistance.” You can view the attached file here. It listed several dozen business names with dates, indicating that testing help for companies mostly ended in early June. Yet Iowa Select Farms got drive-through testing in mid-July.

Important context was missing. Crucially, the document didn’t specify which businesses got strike teams, rapid response teams, or test kits only. No company was listed as receiving help on June 4, which had been a strike team date, according to the document I’d received in January.

Finally, IDPH provided an updated and partially corrected pdf file on April 26. You can download it here, but the formatting makes it hard to read, so I transferred the data into three tables: one showing where strike teams were deployed, one listing companies that received test kits, and one listing companies referred to Test Iowa.

QUESTIONABLE STRIKE TEAM CHOICES

Reynolds had announced the strike team program during a televised news conference on April 16, 2020. The document IDPH gave me in January showed the first strike team was deployed one week later. But it turns out that five previously undisclosed strike team visits occurred before April 23.

According to Ekstrand, licensed health care providers working for the IDPH, Iowa Department of Human Services, or volunteer nurses administered the COVID-19 tests. “The responsibility of the National Guard was transporting supplies, directing traffic flow and flow of persons through the test site only, not actual collection of tests.”

| Business name | strike team date | employees tested | disclosed in January? |

| National Beef/Iowa Premium (Tama) | April 16 and 17 | 656 | no |

| Tyson (Columbus Junction) | April 17 | 859 | no (test kits reportedly sent) |

| Prestage (Eagle Grove) | April 20 | 855 | no |

| Upper Iowa Beef (Lime Springs) | April 21 | 151 | no |

| Lynch Livestock (Waucoma) | April 22 | 49 | no |

| Tyson (Perry) | April 25 | 1,261 | yes (date given as April 23) |

| Tyson (Waterloo) | April 26 | 2,540 | yes (date given as April 24) |

| West Liberty Foods (West Liberty) | April 30 and May 1 | 780 | no |

| Perdue Farms (Sioux City) | May 4 | 144 | yes |

| Perdue Farms (Sioux Center) | May 5 | 281 | yes |

| AgriStar (Postville) | May 5 | 470 | yes (business name redacted) |

| Stine Seed (Adel) | May 8 | 244 | yes (business name redacted) |

| GMT Corporation (Waverly) | May 22 | 200 | yes (business name redacted) |

| Northwood Foods (Northwood) | May 29 | 150 | yes (business name redacted) |

| Bayer (Iowa County location) | June 4 | 47 | yes (business name redacted) |

| West Liberty Foods (Mount Pleasant) | June 5 | 600 | yes (business name redacted) |

| Iowa Select Farms | July 13 | 33 | no |

Most of the companies listed are large food processing companies, which makes sense, because that kind of facility was spawning the largest COVID-19 outbreaks in the country last April and May. The purpose of the strike team effort was to target long-term care facilities and large businesses where COVID-19 outbreaks “are occurring or anticipated,” Reynolds had said when rolling out the program.

So sending the National Guard to facilitate testing at the Prestage pork processing plant doesn’t raise red flags for me. Yes, the family owners had donated a total of $60,500 to the governor’s campaign. But given the outbreaks at Tyson plants, Iowa Premium Beef, and JBS in Marshalltown, there were strong grounds to suspect some Prestage workers were infected and could transmit the virus widely.

A strike team for Stine Seed also seems defensible. Yes, founder Harry Stine is an occasional Republican donor (though never to the Reynolds campaign), as well as Iowa’s wealthiest man. But Dallas County was an early hot spot, and 730 COVID-19 cases had recently been identified among Tyson workers in Perry. According to Stine spokesperson David Thompson, several employees had tested positive prior to the strike team visit, and more than 10 percent of those tested on May 8 were infected. That indicates an appropriate use of surveillance testing. (In contrast, GMT Corporation had only one positive case in the workforce prior to the strike team visit, and no one tested at that company on May 22 was infected.)

Other choices appear less logical. Lynch Livestock received one of the first strike team visits, even though it’s a much smaller workplace than most of the others listed. Owner Gary Lynch has given the governor’s campaign more than $100,000 over the years (see here and here). He is personally acquainted with Reynolds and paid $4,250 at a 2019 charity auction to spend “an afternoon with Iowa’s leading lady.”

Iowa Select Farms had no confirmed cases at its administrative headquarters in July–only some people “potentially exposed to a positive employee” in a different location, a company spokeswoman told Bleeding Heartland. The state hadn’t sent any strike teams to workplaces for more than a month and had never assigned the National Guard to facilitate the process for a group as small as 33 employees.

Moreover, the Test Iowa program had ramped up and was performing thousands of tests a day by mid-summer. Reynolds often touted that program as a resource for businesses needing to test their employees. In June, the state had opened a drive-through Test Iowa site in Waukee, which was operational the week of July 13. It would have been a short drive for anyone working at Iowa Select Farms headquarters.

A review of companies that did not receive a strike team visit raises more questions about the state’s priorities.

SOME CANDIDATES FOR A STRIKE TEAM DIDN’T GET ONE

I created the following table using data from the IDPH on companies that received COVID-19 testing kits from the state, but not state personnel to administer the tests. Those firms typically contracted with a local provider to conduct the testing. For instance, nurses from MercyOne Des Moines handled that task for the wind turbine manufacturer TPI Composites in Newton. Where not obvious, I added the business locations in parentheses.

Local public health departments administered the tests for three of these businesses: Osceola Foods, Versova/Center Fresh Group, and Hormel in Dubuque. Ekstrand told me, “If there is a field that is labeled ‘unknown’, this means that the state does not have a record of the information. Arrangements in these circumstances were made by a number of different staff who were working on the pandemic response at the time.” Why the IDPH would not maintain a central file on state-assisted COVID-19 testing at large workplaces is anyone’s guess.

| Business name | testing date | employees tested |

| TPI Composites (Newton) | April 25 | 1,000 |

| Wells Dairy (Le Mars) | April 29 | 1,000 |

| Midwest Premier Foods (Johnston) | May 4 | 60 |

| Versova/Center Fresh Group (Sioux Center) | May 19 | 1,000 |

| Osceola Foods (Osceola) | May 19 | 924 |

| Seaboard Triumph (Sioux City) | week of May 20 | unknown |

| National Beef/Iowa Premium (Tama) | May 25 | unknown |

| Whirlpool (Middle Amana) | May | unknown |

| Progressive Processing (owned by Hormel in Dubuque) | May | 200 |

| Hormel Foods Knoxville | May | 100 |

| Hormel Foods Algona | May | 150 |

| Redwood Farms (Estherville) | May | unknown |

| Raining Rose (Cedar Rapids) | May | unknown |

| EFCO (Des Moines) | May | unknown |

| Osmundson Manufacturing (Perry) | May | unknown |

| Pine Ridge Farms/Smithfield (Des Moines) | May | unknown |

| Rembrandt Foods (Spirit Lake) | N/A | unknown |

| SEKISUI Aerospace (Orange City) | N/A | unknown |

| CF Industries (Sergeant Bluff) | N/A | unknown |

TPI employs more than 1,000 people in Jasper County. At least two workers had tested positive for COVID-19 by April 10, 2020. Why wouldn’t this company be one of the first to get a strike team? The workforce had 150 confirmed cases and one pandemic death by early May.

Wells Dairy is the country’s second-largest ice cream manufacturer. Versova is a large egg-producing facility. The massive Seaboard Triumph pork plant had eleven confirmed cases by the end of April, and one of those employees died during the first few days of May.

For some reason, IDPH sent test kits rather than strike teams to each of those workplaces around May 19 or May 20. Meanwhile, GMT Corporation (with its one confirmed case among some 200 employees) had a strike team visit on May 22.

This last table shows businesses referred to Test Iowa sites in their area. In most cases, the state did not have records showing how many employees received a COVID-19 test at one of these sites, nor was a specific testing day recorded. The public-private partnership set up testing areas in many different locations, sometimes for a week or two in smaller communities and sometimes for months at a time in larger metros like Des Moines or Cedar Rapids.

| Business name | dates tested | employees tested |

| General Mills (Carlisle) | April 29 | unknown |

| General Mills (Cedar Rapids) | April 29 | unknown |

| Red Star Yeast (Cedar Rapids) | May 6 | unknown |

| Godbersen Smith Construction (Ida Grove) | May 19 | 80 |

| Godbersen Equipment Company (Ida Grove) | May 19 | 20 |

| Bobalee Hydraulic (Laurens) | May 19 | 120 |

| KraftHeinz | N/A | unknown |

| KraftHeinz (Cedar Rapids) | N/A | unknown |

| KraftHeinz (Mason City) | N/A | unknown |

| JBS Ottumwa | Week of May 14 | 2,400 |

| Smithfield (Denison) | week of May 14 | 1,500 |

| Quality Food Processors (Denison) | week of May 14 | 240 |

| GOMACO (Ida Grove) | week of May 18 | 100 |

| KraftHeinz (Davenport) | week of May 25 | 780 |

| JBS Marshalltown | May | unknown |

| Smithfield (Carroll) | May | unknown |

| Smithfield (Mason City) | May | unknown |

| Smithfield (Sioux Center) | May | unknown |

| Smithfield (Sioux City) | May | unknown |

Asked what a “Test Iowa link” from the state entailed, Ekstrand told me, “When a business was provided a URL, specimens were collected for testing at a Test Iowa Drive through Site, persons employed at that business were scheduled through the test IA URL and given certain hours of available testing times at the drive through.”

Sounds like a logical solution for a small office like Iowa Select Farms’ headquarters. Why were so many large food processing plants directed to Test Iowa, though?

By April 20, a few days after Reynolds announced the strike team initiative, JBS Marshalltown already had 34 confirmed COVID-19 cases, and Marshall County as a whole had 173 cases. Howard County (containing Waucoma) had confirmed just four cases as of April 20. Yet the state deployed a strike team to test 49 employees at Lynch Livestock on April 22. Why not send the National Guard and IDPH personnel to JBS?

Wapello County had rapidly growing case counts during the first few days of May, but the Test Iowa site close to the JBS pork plant in Ottumwa didn’t open until May 13.

Denison Mayor Pam Soseman told Radio Iowa in early May she’d been asking state officials for COVID-19 testing in her community after seeing other pork plants become “hot spots.”

National data indicates meat packing has more foreign-born workers than any other industry in the country. Soseman is worried the Test Iowa app that screens people for testing may not be understandable to all the packing plant workers in Denison.

“With 26 languages spoken in our high school, that is a deep concern of mine,” she said. “I also have a concern with those who may not have access to a computer to be able to sign up online, so I’m asking for those who can help to communicate this to people who may be in danger or at risk, to communicate with those people and assist them with that website.”

Similar concerns would apply to other communities where meatpacking jobs have drawn large immigrant populations. Bringing a strike team to those workplaces would have made the testing more accessible and not easily derailed by language barriers.

As mentioned above, the governor’s office did not respond to my inquiries about why certain companies were chosen for strike teams. But Reynolds’ spokesperson Garrett told the AP’s Foley on April 27, “Political support wasn’t a factor, ever. All these decisions are made in conjunction with public health based on the needs of a company that would come to us.”

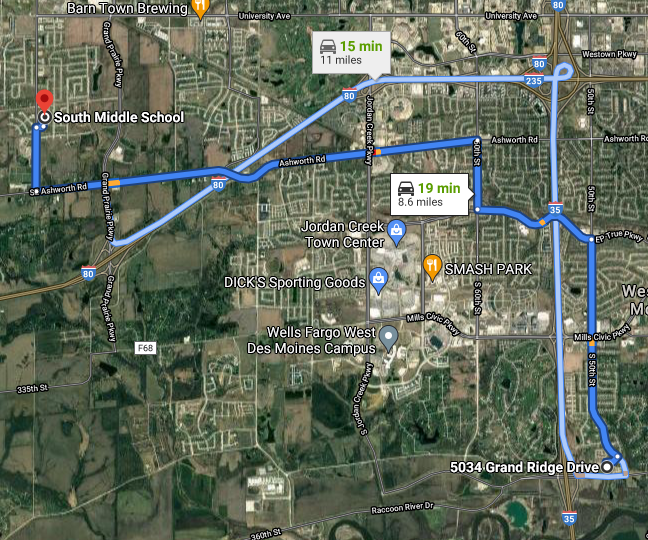

Which “needs” factored into those decisions? Who in the public health department signed off on the choices? The strike teams weren’t sent to the businesses with the most confirmed cases, nor was there any consistent standard based on size of a company’s workforce or spread in the surrounding community. Iowa Select Farms headquarters clearly didn’t “need” to have the state send over a strike team. Executives could have scheduled appointments for staff at the Test Iowa site less than a 20-minute drive away.

“I WILL NOT PROVIDE RESPONSES TO ADDITIONAL INQUIRIES”

In an April 28 email that answered some of my questions and ignored others, Ekstrand wrote, “What I have provided to you is the result of hours of work researching and compiling information to create a specific document, and respond to your follow up inquiries. As we are still very much engaged in pandemic response, that is where we need to focus time and resources, so I will not provide responses to additional inquiries on this topic.”

Speaking of “hours of work researching,” I wish I didn’t have to circle back five, ten, or more times with questions that may or may not be answered truthfully, or at all.

I wish the agency coordinating the COVID-19 response would provide reliable information the first time, so I wouldn’t have to ask again and again whether a document I received was complete and accurate, only to learn (months later) that big pieces of the picture were missing.

In all likelihood, Ekstrand is not calling the shots on how much to tell reporters or how long to make them wait. State agencies routinely run media queries and public records requests through the governor’s office now. (That wasn’t standard practice prior to the pandemic.) Former IDPH communications director Polly Carver-Kimm alleged last year in a wrongful termination lawsuit that Garrett once told her to “hold” records already approved for release.

One person not constrained by this game-playing is Sand. The State Auditor’s office has subpoena power, and Sand isn’t afraid to use it. Public information officer Sonya Heitshusen confirmed last week that auditors continue to review the state’s use of strike teams for COVID-19 testing. As for an expected completion date, “there is no timeline. The investigation will be complete when it’s complete.”

Top image: Iowa Select Farms administrative headquarters in West Des Moines, photographed by Laura Belin.