Evan Burger previously wrote about Iowa Congressional and state legislative redistricting scenarios. -promoted by Laura Belin

Today I’ll continue my ongoing series on redistricting with a deeper dive on Iowa legislative redistricting, using Story County as a case study. A few general updates to start:

First, the partisan battle lines over Iowa redistricting are starting to shape up. According to several press reports, including this recent Des Moines Register article, Republican leaders are floating the idea of suing the Census Bureau to get data earlier than September 30th:

“We’re tasked with trying to design a map by Sept. 1 when the Biden administration is not going to give us any of that data until Sept. 31. And so that’s a problem,” [Jack] Whitver, a Republican, said at a forum hosted by the Ankeny Area Chamber of Commerce. “And just to be blunt, I don’t know how to address it yet. We’re looking at all options, and everything from suing the Census Bureau to make sure that we get that data to any other options on the table.”

Ohio and Alabama have already filed lawsuits with similar aims. Those cases are still making their way through the courts, but they have been successful in one respect: the Census Bureau has agreed to release final data slightly earlier than planned, albeit in an outdated format. “Tabulated” results will still be released on September 30, but “legacy format” results will now be released in mid- to late-August.

However, this seems to be the limit of what the Ohio and Alabama lawsuits will accomplish. The whole point of the census is to produce accurate numbers – it’s hard to imagine a scenario where the courts decide that making things convenient for redistricting authorities overrides the requirement for accuracy. The district judge who threw Ohio’s lawsuit gave precisely this reasoning, and I anticipate the same will be true at the appellate level.

In the Iowa context, the Legislative Services Agency (LSA) is still evaluating whether they will be able to start redistricting with the legacy format results, or whether they will need to wait for tabulated results. Even if the LSA determines that legacy format data can be used, mid-August does not allow for enough time to meet the constitutional requirement to finish redistricting by September 1. Two or three weeks is still not enough time to process the data, present an initial plan, hold public hearings, and vote to approve the plan.

In contrast to the Republican strategy, James Q. Lynch with the Cedar Rapids Gazette reports that some Democrats seem open to having the Iowa Supreme Court take over the process:

[S]ome Democrats privately have welcomed the delay as [a] way to prevent Republicans from approving a map favorable to holding its legislative majority. They speculate Republicans will reject the first two plans from the LSA so they can amend the third plan to their advantage before approving.

In my opinion, allowing the Supreme Court to take over redistricting does not ensure fair maps. In the past, when the state supreme court got involved in map-drawing, it turned out fine – but that was before six of Iowa’s seven Supreme Court justices were appointed by Republicans. And if Governor Kim Reynolds and Republican leadership indicate publicly and loudly that they don’t want the court to take over redistricting, I have a hard time believing that the justices would choose to ignore them. As I’ve mentioned before, the California Supreme Court extended redistricting deadlines to allow for the standard process to take place; that seems to be the route of least resistance for Iowa’s justices as well.

So in spite of the partisan posturing at the legislature, the Supreme Court still holds all the cards on how Iowa redistricting will play out – and the justices are staying tight-lipped.

In the meantime, we can keep speculating on what the final maps will look like. I chose Story County as the topic of today’s article for two reasons: first, it’s my home county; and second, it’s a good case study of the challenges with making county-level legislative predictions.

Story County overview

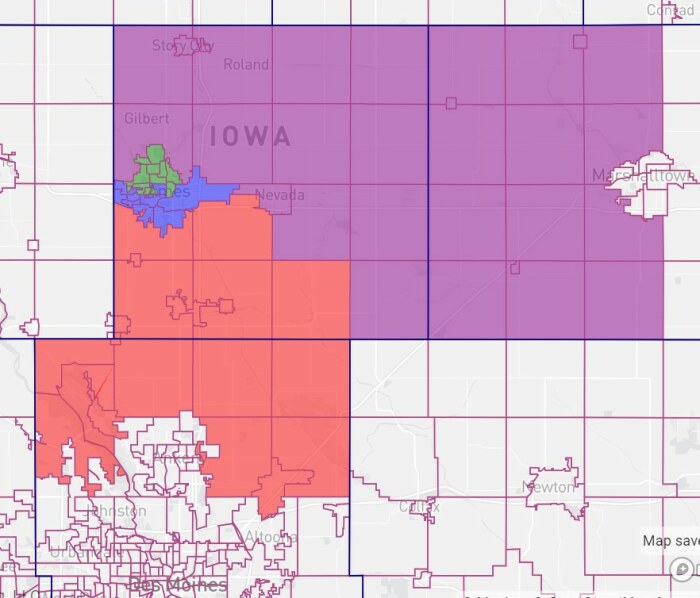

Story County is made up of forty-three precincts, twenty of which make up Ames, four Nevada, and nineteen the rest of the county. Currently, those forty-three precincts are split among four state House districts and three Senate districts:

In order to predict what new districts will look like in Story County, we come up against three main challenges: finding up-to-date precinct maps, getting precinct-level population counts, and estimating the impact of COVID-19 on census results.

Challenge #1: Up-to-date precinct maps

One thing we know is that legislative districts will be made up of whole precincts. Unfortunately, precinct boundaries can change over time, so our first challenge in making predictions about Story County redistricting is to determine what the current precinct boundaries are.

This is a harder task than it might seem. The most common cause of precinct boundary changes is the annexation of land by cities – county auditors, for obvious reasons, usually update precinct boundaries to match the new city limits – and Story County has several cities that have annexed land since the last round of redistricting.

There are several public resources of the current precinct boundaries in Iowa, but none of them are perfect. (Presumably, the LSA has good precinct maps, but those are not public.) The Secretary of State’s central database of precinct shapefiles reflects only the 2010 boundaries, and directs visitors to the auditor’s website for more up-to-date maps.

However, the precinct maps provided by the auditors vary widely in quality. Even in Story County, a large county with a well-run auditor’s office, the countywide precinct map was last updated in 2015, and therefore does not reflect precinct boundary changes made since then. (For example, compare the eastern boundary of Ames 1-3 on the countywide map with the same area on the auditor’s Ames inset.)

The same problem applies to another central database, the OpenPrecincts project. This website aims to track precinct boundaries for the entire country as of the 2016 presidential election. So while its Story County map is slightly more up-to-date than the auditor’s map, it still does not reflect changes like Ames 1-3.

Problems with precinct boundaries are even more widespread in the popular redistricting websites that allow you to draw hypothetical new district boundaries. Even my favorite of these tools, Dave’s Redistricting App (DRA), which just did a major precinct update, has three major errors in Story County:

- Nevada is shown as a single precinct instead of four.

- Cambridge and Union Township are shown as separate precincts when in reality they are combined into one precinct.

- Similarly, Kelley should be included with Washington Township but is displayed separately.

Fortunately, we can account for these three errors pretty easily. For Cambridge and Kelley, we just need to make sure that each city is always districted with its township in any hypothetical map. And the inaccurate Nevada boundaries are moot thanks to Section 4.2 of Chapter 42 of Iowa Code:

To the extent consistent with [the principle of equal population], district boundaries shall coincide with the boundaries of political subdivisions of the state. The number of counties and cities divided among more than one district shall be as small as possible. When there is a choice between dividing local political subdivisions, the more populous subdivisions shall be divided before the less populous, but this statement does not apply to a legislative district boundary drawn along a county line which passes through a city that lies in more than one county.

In practice, this means that cities that have a smaller population than the ideal House district population will almost certainly be kept together in a single district, unless they span multiple counties. With a population of roughly 6,700, Nevada falls in this category, so DRA’s flaw of counting Nevada as a single precinct means that we can still use the tool to draw draft Story County maps.

However, uncertainty about the exact boundaries of precincts like Ames 1-3 still persists. DRA shows Ames 1-3 extending further north than either the auditor’s countywide map or the auditor’s citywide map does, so we actually have three competing definitions of the boundaries for that precinct. This problem bleeds into the second challenge: getting precinct-level population counts.

Challenge #2: Precinct-level population counts

Just as we know that legislative districts will be made up of whole precincts, we know that the first step of drawing legislative districts is to apply the standard of equal population. As mentioned in my last piece, we can estimate that the ideal House district population will be roughly 31,500 and the ideal Senate district population will be roughly 63,000.

When the LSA draws Iowa’s maps, the acceptable variance from this ideal is very low: in 2011, the ideal house district population was 30,464, while the largest house district had a population of 30,763 and the smallest was 30,176.

In other words, every house district had a population within 1 percent of the ideal. So if our estimate of 31,500 for the ideal 2021 House population is correct, the full range of acceptable populations for a House district would be something like 31,200-31,800 people.

DRA’s precinct-level population estimates are based on the Census Bureau’s 2018 population estimates.These estimates are subject to uncertainty in several dimensions. First, as mentioned above, the underlying precinct boundaries are not perfectly accurate. Second, the Census Bureau’s annual population estimates will diverge to some degree from the decennial census results. And finally, the decennial results are themselves subject to uncertainty due to the ongoing pandemic. This final kind of uncertainty constitutes the third and final big challenge with county-level redistricting estimates.

Challenge #3: COVID-19 impact on census results

Conducting a census during the COVID-19 pandemic led to many challenges. For one thing, in-person enumeration tactics like door-knocking were harder. But even worse, the pandemic means that certain populations, like college students, were not physically present in the places where they should be counted.

As the home of Iowa State University, Story County is particularly vulnerable to potential inaccuracies due to the pandemic. The decennial census tracks each person’s residence as of April 1 of a year ending in 0. By April 1 of last year, Iowa State had gone fully remote, leading Ames city leaders to express concern about possible undercounting of students.

These concerns are validated by the census’s official self-reporting rates for Ames, which show that the most student-heavy census tracts in Ames had self-response rates much lower than the city-, state-, or national average. The Census Bureau attempted to correct for this error by working with university administrators to find on- and off-campus addresses for students.

We won’t know how successful they were until they release final numbers. But since students make up almost half of the population of Ames, if even 10 percent of students are counted at their parents’ address rather than their school address, it will have major implications for Story County’s new legislative districts.

Story County scenarios

These three interrelated challenges mean that we should take precinct-level population estimates like those provided by DRA with a grain of salt. Decennial census counts always diverge from annual population estimates to some degree, but changing precinct boundaries and the pandemic mean that 2020 Story County estimates in particular might diverge even more than usual.

And thanks to Iowa’s robust redistricting process, that uncertainty makes predictions at this level very difficult. When the population of a House district has to fall within a range of just 600 people (i.e., in between 31,200 and 31,800), a decennial count in a single precinct that differs from estimates by just dozens of people could change the entire county’s district map. In the context of this uncertainty, here are my best guesses for different Story County scenarios, driven mostly by how well or poorly the Census was able to count Iowa State students.

Scenario 1: High Ames population

In 2019, the annual Census estimate of the population of Ames was 66,258, while the rest of the county was estimated to be 30,859. That puts Ames right above two house districts, and the rest of the county right below one house district.

If the decennial census count for Ames comes in above 63,600, the twenty Ames precincts will have to be divided among three House districts. There are two main ways that could play out: Ames could either end up looking like Council Bluffs, or it could end up looking like Waterloo.

In 2010, the population of Council Bluffs was slightly higher than twice the ideal House district population. The LSA chose to make two districts that were exclusively, or almost exclusively, made up of Council Bluffs precincts: House districts 15 and 16. The remaining Council Bluffs precincts were then combined with most of the rest of Pottawattamie County to make House district 22. The eastern-most precincts of Pottawattamie County were then combined with Cass, Adams, and Union County to make House district 21.

The 2019 Ames and Story County population estimates lend themselves well to a map like that – for example, this map that I made with DRA:

However, that’s not the only possible way to handle a high Ames population. Whoever ends up drawing the maps could also choose to treat Ames like Waterloo was treated in 2011.

Much like Council Bluffs, in 2010 Waterloo was too big for two house districts but far too small for three. Instead of making two Waterloo house districts and putting the remainder of the city with other parts of the county, the LSA chose to divide Waterloo pretty evenly among House districts 60, 61, and 62.

Applied to a high-population Ames scenario, this route might look something like this:

A Waterloo-type outcome would probably benefit Democrats, by creating three Ames-dominated districts rather than two plus a rural district.

Scenario 2: Medium Ames population

But both the Council Bluffs and Waterloo examples rely on the 2019 population estimates being roughly correct. If the decennial census count for Ames instead falls between 62,400 and 63,600, due to undercounting ISU students, Ames will likely be drawn into exactly two House districts.

That would leave the rest of the county slightly too small for a House district of its own. Therefore, it could either be kept whole, and lumped in with a few precincts from a neighboring county, or it could be split between two house districts like it is now. Here are maps showing examples of these two options:

Or split between House districts:

Scenario 3: Low Ames population

However, students could be undercounted even more drastically. If the census undercounts ISU students by 12 percent or more, the population of Ames will come out as less than 62,400. In that case, we will probably see a new map very similar to the current map, where one House district is contained within Ames and another is the remaining Ames precincts plus some rural precincts:

Like Scenario 2, the rest of the county could then be kept together and combined with some precincts from a neighboring county, or it could continue to be split between two house districts.

Finally, in all three scenarios, at least one Senate seat will likely be dominated by Ames. Even in a Waterloo-type outcome, Section 4.2 of Chapter 42 strongly inclines the map-drawing authority to combine two of those house districts into a senate district, rather than splitting Ames among three Senate districts.

Conclusion

As the Story County example shows, legislative redistricting predictions for specific counties or cities are much more difficult than Congressional or chamber-level predictions. However, not all counties are quite as difficult as Story.

For one thing, aside from Johnson County (Iowa City area), most counties do not have a large student population, and will therefore have less uncertainty around COVID-19’s impact on census results. And for reasons I plan to explore in my next entry in this series, precinct boundaries and precinct-level population are not as important for small counties. Stay tuned, and in the meantime, follow me on Twitter (@evan_burger) for the latest redistricting news.

Evan Burger is a longtime political organizer who lives in Slater. He was the Iowa caucus director for Bernie Sanders’ 2020 campaign, and is now a partner at the progressive consulting firm Hegemony Strategies.