Spenser Mestel is a freelance journalist and author of Spenser’s Super Tuesday, a weekly newsletter about voting rights. -promoted by Laura Belin

The race in Iowa’s second Congressional district, the closest U.S. House election since 1984, isn’t over just yet.

On December 22, Democratic candidate Rita Hart filed a “notice of contest” in the House, officially challenging the six-vote margin that separates her from Republican Mariannette Miller-Meeks. Now, the issue goes to the House Administration Committee, which recently agreed on rules to hear the case. Should it agree to investigate further, the winner could be decided by a majority vote in the House.

Hart’s bid is a long-shot. In the last 107 elections to be contested under the Federal Contested Elections Act, 104 failed. However, other circumstances favor Hart: Democrats control the chamber (221 to 211) and have already taken the unprecedented step of expelling Republican Marjorie Taylor Greene from her two committees. Plus, the Hart campaign has credible evidence that the initial vote-counting and subsequent recounting were flawed.

“TWO SETS OF ERRORS THAT MARRED THE CERTIFIED VOTE TOTAL”

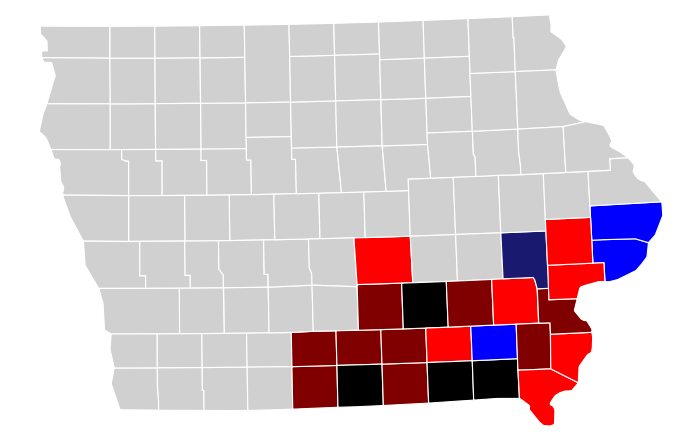

In its brief, the Hart campaign alleges that election officials in IA-02, which covers the southeastern part of the state and includes 24 counties, made two mistakes.

The first was that, during the initial count, poll workers wrongfully threw out 22 absentee ballots for various reasons, like they were rejected by the machine tabulator or were signed in an unusual place. Though the counties later determined that these ballots were lawfully cast, they argued that, because they were omitted from the original count, they were also ineligible to be recounted. Of these 22 voters with uncounted ballots, eighteen voted for Hart, three for Miller-Meeks, and one did not vote for either candidate–producing a net gain of fifteen votes for Hart, enough to make her the winner.

The second mistake was that counties used different standards to recount a small subset of ballots, so a vote that would be counted in one jurisdiction would be thrown out in another, which is unconstitutional.

What produced the biggest difference between counties was whether they chose to recount the votes by hand or by re-running them through the machine tabulators. Doing the latter almost guaranteed the same result because the counters are incredibly consistent — and accurate, except in rare cases.

Imagine a voter is agonizing between the two candidates. He goes to vote for the Democrat but changes his mind at the last moment, leaving a tiny pen mark by her name before filling in the oval for the Republican. The machine reads each of these marks as a vote and disqualifies the ballot.

It’s clear to a human what the voter’s intent was, but only six of the district’s 24 counties recounted all of their over-votes by hand — and twelve didn’t review any over-votes at all. In fact, those twelve counties didn’t visually inspect a single over-vote, write-in, or under-vote (when the tabulator says a voter didn’t choose any candidate).

In absolute terms, these ballots were rare (there were only 175 over-votes out of about 390,000 ballots), but combined, they could easily flip the Congressional race.

“SOME RULES SHOULD BE AMENDED AND OTHERS SHOULD BE ABANDONED ALTOGETHER”

The IA-02 contest didn’t just expose a few mistakes and inconsistencies. It also revealed election laws that are both unfair and irrelevant, says University of Iowa Law Professor Todd Pettys in a recent article in the Iowa Law Review.

For one, there’s the unrealistic deadlines. Regardless of their population, counties had roughly eight days to recount ballots — but each canvassing board was limited to just three people. To make matters worse, at least in Johnson County, the tabulators couldn’t be used to sort out under-votes, over-votes, and write-ins because reprogramming the machines violates state law.

Another problem was that any ballot with an identifying mark had to be discarded. Though Professor Pettys says this law made sense when it was originally passed, during a time when vote-buying was a common practice, its effect now is to disenfranchise well-intentioned voters, like the one who wrote her name and address at the bottom, presumably so she could be contacted if there were a problem.

Finally, voters who used a “non-standard” mark (like marking an X instead of filling in the oval) had their vote counted — but only if they used the same non-standard mark for every race on the ballot. “In each of those instances,” wrote Pettys, “it seemed clear that the cure was far worse than the disease.”

“AVAIL THEMSELVES OF EVERY SINGLE REMEDY”

For their part, the Miller-Meeks campaign has argued that the House Administration Committee should throw out Hart’s case because she didn’t pursue legal action through Iowa’s courts. Instead, she went straight to the federal level. Though this is true, the Federal Contested Elections Act does not require candidates to exhaust their in-state options. (A House Democrat’s effort to throw out a Republican’s appeal on the same grounds failed in 1997.) Furthermore, it is the House that ultimately has the power to decide who it seats.

Miller-Meeks was sworn in as the representative for IA-02 in early January. However, should a majority of the House decide otherwise, Hart will take over that position.

Click here to subscribe to Spenser’s newsletter. Every Tuesday, it highlights a new, under-reported topic in the fight for voting rights. No jargon, no ads, and never more than a six-minute read.

Top image: Map of certified county-level results in the Hart/Miller-Meeks race. Click here to access the interactive map and related tables.