Since the Iowa Department of Public Health (IDPH) changed how it counts and reports COVID-19 deaths on December 7, fatality numbers on the official website coronavirus.iowa.gov have become more accurate in several respects. The state’s dashboard no longer routinely lowballs how many Iowans have died in the pandemic. Instead, the IDPH numbers track closely with weekly figures published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

We now know that COVID-19 deaths accelerated in Iowa this fall even more rapidly than was previously apparent. Through the end of November alone, at least 3,308 Iowans had died in the pandemic. That number was more than 600 higher than the state website indicated before the IDPH began implementing the new counting method.

Two drawbacks have accompanied this important policy change. First, there is a greater lag time between when an Iowan dies and when that fatality tends to appear on the dashboard. In addition, updates to the state website have become more erratic, with IDPH staff adding few or no deaths on some days, and more than 100 deaths on others.

Now more than ever, media organizations that report COVID-19 statistics daily must put those numbers in context. Anyone following news on the pandemic needs to understand that changing totals from one day to the next on the IDPH website do not reflect how many Iowans died of COVID-19 during the previous 24 hours.

That said, the more accurate counting method is bringing the horrifying scale of the pandemic into focus.

HOW IOWA’S COUNTING CHANGED

IDPH interim Director Kelly Garcia announced the change at a December 7 video news conference accessible only to invited journalists. From Clark Kauffman’s write-up for Iowa Capital Dispatch:

“We’ve recognized a need to adjust our death reporting,” Garcia said Monday [December 7]. She said the state did not change its methods earlier because there was no statistically significant difference in the death counts, and the old system allowed for faster collection of data.

Under the previous methodology, she said, the state recognized a COVID-19 death when a positive test result for the virus was matched to a death certificate. And because each case had to be matched to specific kind of test — a PCR test — deaths that were clinically diagnosed with no such test, and deaths that were matched only to a positive antigen test, were not counted.

An agency news release explained that the IDPH typically relies on an international coding system to classify deaths from various diseases. No such code existed for COVID-19 early this year. Now that one has been created, the state will use that code going forward to determine whether an Iowa deaths was coronavirus related, even if the IDPH has no positive test result on record.

NEW POLICY CORRECTED A GROWING PROBLEM

At the time of Garcia’s news conference, the IDPH asserted the new counting method would raise Iowa’s death toll by 175, from 2,723 to 2,898. State employees removed 433 deaths and added 610 when implementing the policy, reporters were told.

In reality, the discrepancy was much larger than 175. Since December 7, most of those 433 cases have been added back to the numbers reported on the state website, as IDPH staff caught up with checking death records.

I created this graph to compare the daily death numbers that appeared on coronavirus.iowa.gov before the switch with the numbers for each date currently displayed on the dashboard. You can see that in the early months, the “old” state numbers were not far off the “new” ones. That changed in September, perhaps because antigen testing began to be used much more widely in senior care facilities, where a large percentage of Iowans killed by the virus had resided.

The next graph shows the cumulative number of deaths reported in Iowa at the end of each month since the pandemic began. Again, the “old” and “new” lines begin to diverge in September. By the end of October, the old method was more than 100 deaths short, and that discrepancy grew to more than 600 by the end of November–far more than I realized when researching the state’s regular undercounting of deaths last month.

To provide another view of the problem, I created the next graph to show the daily numbers from September 15 to November 15. I picked an ending date in the middle of November because even under the old system, deaths were commonly added to the state website one to two weeks after the patient had passed away. So as of December 7, death numbers for the last ten days or so of November could be expected to increase further. But numbers on or before mid-November should have been close to final.

You can see why IDPH staff realized they needed to address the problem.

NEW NUMBERS REFLECT ACCELERATING PACE OF COVID-19 DEATHS

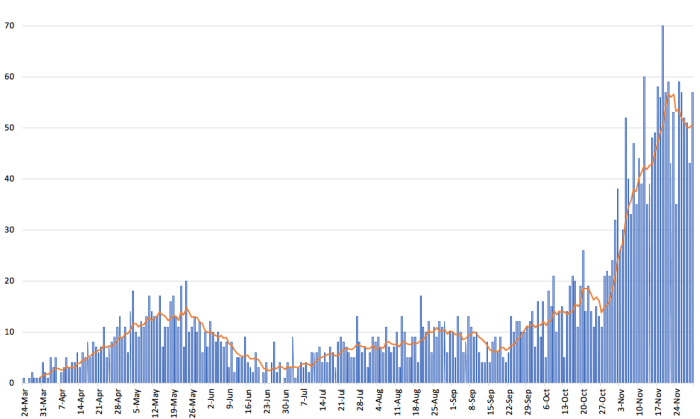

This bar graph reflects numbers as they appeared on the state website on December 20. Fatalities are attributed to the date on the death certificate. The orange line represents the seven-day moving average of COVID-19 deaths in Iowa.

During the first peak, our state’s deadliest day for COVID-19 was May 24, when 20 Iowans died. We’ve exceeded that death toll each day since October 29. Thirty or more Iowans died on every day but one in November. At least 40 died on more than half the days last month. At this writing, the deadliest day is November 19, when at least 70 Iowans died of the virus. That number may increase as more death certificates are processed.

I find it informative to track the pace at which Iowans are dying of COVID-19, which isn’t obvious from eyeballing the bar graph. Working from the more accurate new daily totals, I tabulated Iowa’s cumulative deaths for each date again. The results show how quickly fatalities began piling up this fall, following record high case and hospitalization numbers.

Even though Iowans were dying at the fastest pace yet in late October, Governor Kim Reynolds focused on campaigning for Republican candidates and did nothing to strengthen the state’s COVID-19 mitigation efforts until after the general election.

The IDPH reported our state’s first COVID-19 death on March 24. Then, it took:

28 days to pass 100 total deaths (April 21)

twelve days to pass 200 (May 3)

seven days to pass 300 (May 10)

eight days to pass 400 (May 18)

seven days to pass 500 (May 25)

ten days to pass 600 (June 4)

22 days to pass 700 (June 26)

23 days to pass 800 (July 19)

fourteen days to pass 900 (August 2)

thirteen days to pass 1,000 (August 15)

eleven days to pass 1,100 (August 26)

ten days to pass 1,200 (September 5)

thirteen days to pass 1,300 (September 18)

eleven days to pass 1,400 (September 29)

eight days to pass 1,500 (October 7)

eight days to pass 1,600 (October 15)

five days to pass 1,700 (October 20)

seven days to pass 1,800 (October 27)

five days to pass 1,900 (November 1)

three days to pass 2,000 (November 4)

two days to pass 2,100 (November 6)

three days to pass 2,200 (November 9)

two days to pass 2,300 (November 11)

two days to pass 2,400 (November 13)

three days to pass 2,500 (November 16)

one day to pass 2,600 (November 17)

two days to pass 2,700 (November 19)

two days to pass 2,800 (November 21)

two days to pass 2,900 (November 23)

two days to pass 3,000 (November 25)

two days to pass 3,100 (November 27)

one day to pass 3,200 (November 28)

two days to pass 3,300 (November 30)

Total through November 30: 3,308

Given the longer delays in reporting under the new system, total deaths through November will likely increase further. Of the 138 deaths added to Iowa’s website between December 19 and December 20, many were attributed to dates in November, one going back as far as November 5.

One other addition to the state’s published data is worth noting.

REPORTING DEATHS IN MULTIPLE WAYS

Aligning with the CDC’s approach, the state dashboard now distinguishes between two kinds of COVID-19 fatalities. Since the earliest weeks of the pandemic, the CDC has recorded “underlying cause” deaths (for which COVID-19 was the underlying cause) and “multiple cause” deaths (for which the virus was “a factor contributing to death”).

On the CDC’s table of weekly causes of death, the “underlying cause” deaths (3,146 for Iowa as of December 20) are a subset of the “multiple cause” deaths (3,431).

Iowa’s website now presents the same concept in a slightly different way. At this writing, the dashboard shows 3,589 total COVID-19 deaths, of which 3,295 are listed as “underlying cause” and 294 involve coronavirus as a “contributing factor” along with other conditions. That conveys the reality that this novel virus is the primary factor in the vast majority of deaths attributed to it.

Unfortunately, the state website still includes “pre-existing condition” data, which may confuse the issue. Reynolds has repeatedly emphasized at her televised news conferences that most Iowans who have died of COVID-19 were elderly or had some underlying health condition. At this writing, coronavirus.iowa.gov reports that 3,299 Iowans who have died had some unspecified pre-existing condition, while 290 had no pre-existing condition.

Those who downplay the severity of the pandemic often point to such numbers as supposed evidence that coronavirus doesn’t kill many people. But some conditions that put someone at higher risk for COVID-19 complications can otherwise be manageable for decades. Dr. Eli Perencevich, a University of Iowa infectious disease specialist and epidemiologist, explained in August, “If you happened to have diabetes and caught COVID, developed pneumonia, and died then COVID killed you. People with diabetes don’t just die of pneumonia daily.”

COMPARED TO MOST STATES, IOWA LOSING MORE PEOPLE TO COVID-19

When asked about worsening trends in Iowa, Reynolds has often remarked that coronavirus cases, hospitalizations, and deaths are increasing all over the country. That’s technically true, but it obscures the big picture: Iowa is doing worse than most states, in terms of deaths as a share of our population.

Charles Gaba regularly creates 50-state graphics on the ACA signups website. The latest version, posted on December 18, shows Iowa is the twelfth worst state for COVID-19 deaths per capita. Most of the states with higher numbers were hit hard in March, allowing the virus to spread widely before mitigation measures were in place.

Among the states that didn’t experience large numbers of coronavirus cases in March and April, only North Dakota, South Dakota, and Mississippi are doing worse than Iowa now in terms of deaths adjusted to the size of the state’s population.

Incidentally, Iowa is now the third-worst state in the country for total COVID-19 cases per capita. Only North and South Dakota, where governors also avoided mask mandates and imposed relatively few restrictions on businesses, are ahead of Iowa on that metric.

FINAL NOTE: A TROUBLING LACK OF TRANSPARENCY

While the IDPH’s commitment to accurate death statistics is welcome, it’s troubling that the state was secretive about the old counting method for months.

The December 7 news release explained that with no established code for COVID-19 deaths, “IDPH relied on a combination of a confirmed positive test result” on a PCR test, “along with case information that indicates the individual is deceased.” The statement argued that this approach “was the best available solution when the pandemic began.”

Why didn’t anyone from the agency just say so?

During the first half of July, I sent more than half a dozen emails to three different IDPH employees who handled communications, asking how the state counted COVID-19 deaths. I never got any answer.

Between August and November, I emailed many more times to inquire about the discrepancy between state and local counts for COVID-19 deaths in Van Buren County. It would have been simple to explain that IDPH was not recording deaths for patients who tested positive on an antigen test. Yet I received no reply, not even “no comment.”

Before reporting last month on the state’s persistent undercounting of deaths, I reached out to the IDPH’s new public information officer. Again, I heard nothing.

Garcia rolled out the new counting method at a news conference to which Bleeding Heartland was not invited. Staff didn’t post the video on the agency’s YouTube channel, making it impossible for other reporters or members of the public to watch the presentation or Q&A, even after the fact.

When asked why I was excluded from a conference about a topic I’d been covering for five months, Sarah Ekstrand replied on behalf of IDPH, “We sent the invite to a list of credentialed reporters and outlets who cover the pandemic.” (The governor’s office has used the same excuse to keep me out of Reynolds’ news conferences, saying I am not “credentialed media.”)

When I asked why no one at IDPH ever revealed the old counting method, Ekstrand replied,

I’ve attached the document we shared that outlines the old methodology, the current methodology and the reason for the change in the way IDPH reports COVID-19 deaths.

This should answer your questions.

I’ve posted the document in full below. It doesn’t address why the agency was secretive about its methodology prior to announcing the change on December 7.

Garcia has been calling the shots at the IDPH since late June. Under her leadership, the agency has knowingly published inaccurate case counts, testing numbers, and positivity rates on coronavirus.iowa.gov.

While the state dashboard no longer undercounts deaths, IDPH continues to hide the number of nursing home staff who have died of COVID-19.

Most recently, Garcia has insisted that a new advisory council on allocating COVID-19 vaccines meet behind closed doors, in apparent violation of Iowa’s open meetings law.

The IDPH interim director talks a good game about transparency but rarely leads by example.

_______________

Appendix: Iowa Department of Public Health news release on “COVID-19 Death Reporting”

1 Comment

And this varied and continuing secrecy is happening in just one Iowa state department.

I wonder what may be happening in the others.

PrairieFan Mon 21 Dec 7:31 PM