Herb Strentz: Today’s reality show from the Oval Office may be following plotlines imagined by 1960s authors with ties to the leading newspapers of Iowa and Minnesota. -promoted by Laura Belin

A provocative “Iowa angle” links fiction of the 1960s to fact in the 2020 dispute between President Donald Trump and several of the nation’s current or former military leaders. Trump advocated using military force to quell national unrest sparked by the killing of George Floyd, an unarmed African American, at the hands of Minneapolis police.

In its June 8 newsletter for subscribers, the well-respected international magazine The Economist characterized Trump’s call to arms as America’s “worst civil-military crisis for a generation, one that threatens to do enduring harm to democratic norms and the standing and cohesion of its armed forces.”

The Iowa angle goes back to the John F. Kennedy era and best-selling novels by former writers at The Des Moines Register and the Minneapolis Tribune, who wrote about scenarios of presidential instability and misuse of the military on American soil.

The Economist quoted Dr. Lindsay Cohn, an assistant professor at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island whose research focuses on civil-military relations. Speaking in her personal capacity, she observed, “This is absolutely the only time I can think of that this many current and former high-ranking military officers have made a very clear pushback against the domestic use of the military.”

Those pushing back include Secretary of Defense Mark Esper and Admiral Mike Mullen, a former chairman of the joint chiefs of staff.

Other military leaders expressing concern include the current chairman of the chiefs of staff, General Mark Milley, and U.S. Marine Corps General and former Secretary of Defense James Mattis. Former Secretary of State Colin Powell, who previously held several high-level military posts, joined in the criticism this past Sunday in his CNN interview with Jake Tapper.

For his part, Admiral Mullen is quoted by The Economist as saying the problem cut to the heart of America’s civil-military relations: “Too many foreign and domestic policy choices have become militarised; too many military missions have become politicised.”

But those breath-taking developments, put in the context of history, show that today’s reality show from the Oval Office may be following plotlines imagined by 1960 authors with ties to the leading newspapers of Iowa and Minnesota, then owned by the Cowles family from Algona.

The scripts were provided some 60 years ago by Fletcher Knebel, then a columnist for the Register and Tribune Syndicate.

He and Charles Bailey of the Minneapolis Tribune cowrote Seven Days in May, published in 1962. Two years later, their novel was adapted for a movie starring Frederic March, Burt Lancaster, and Kirk Douglas.

An off-the record interview Knebel had with Air Force General Curtis LeMay (who ran for vice president on a third-party ticket with George Wallace in 1968) spawned the book and film. Seven Days in May presented a fictional account of an attempted right-wing military coup to oust the president, because of fears of what he might do to national defense.

Consider that in the 2020 context, where military leaders speak out about a non-fictional effort of a sitting president to use his commander-in-chief status for political reasons and to deploy the military to suppress domestic dissent.

The life-imitates-art suggestions become even hairier when you factor in another novel by Knebel, his 1965 book A Night of Camp David.

That “political thriller,’ as characterized at the time, featured a Democratic U.S. senator from Iowa who was summoned to Camp David to discuss a possible candidacy as vice president in the upcoming re-election campaign. During the meeting, the senator suspects the president (who also has voiced desires to align more closely with the Soviets and to sever alliances with European allies) is showing signs of clinical paranoia and a possible descent into madness.

Seven Days in May was on the national best seller list for about a year; Night of Camp David for 18 weeks.

So there’s the Iowa angle, at least as questions unfold about Trump’s use of the military.

Sidebar

Relatedly, two other noted fictional works may be stoking our fears.

One, of course, is George Orwell’s 1949 book 1984, whose fears are well expressed when its main character Winston Smith is told, “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face — forever.”

To many, that can be a metaphor for what so many African Americans have suffered for centuries.

Then, to add to our review of 20th century literature, consider Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, written in 1931.

One poignant takeaway from that book is when ladyfriend Lenina Crowne cautions the main character Bernard Marx to stop paying so much attention to what’s going on. As Huxley wrote, “’I don’t understand anything,’ she said with decision, determined to preserve her incomprehension intact.” She advises Bernard to stop paying attention because then “instead of feeling miserable, you’d be jolly. So jolly.”

In Brave New World Revisited, published 37 years later, Huxley reflected on his most famous work.

I feel a good deal less optimistic […] Democratic institutions can be made to work only if all concerned do their best to impart knowledge and to encourage rationality […]

But today, in the world’s most powerful democracy, the politicians and their propagandists prefer to make nonsense of democratic procedures by appealing almost exclusively to the ignorance and irrationality of the electors. […] The political merchandisers appeal only to the weaknesses of voters, never to their potential strength.

For consolation, we can recall that while the French cry in July 1789 was “To the Bastille,” we can cry “To the Polls” in November 2020.

Herb Strentz was dean of the Drake School of Journalism from 1975 to 1988 and professor there until retirement in 2004. He was executive secretary of the Iowa Freedom of Information Council from its founding in 1976 to 2000.

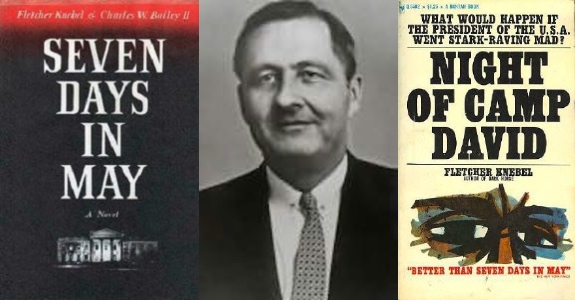

Top image: Fletcher Knebel, center, between photos of the covers of his two most famous novels.