Dan Piller: Donald Trump benefitted from a slumping agricultural economy in 2016, but the Iowa farm economy has slid even further on his watch. -promoted by Laura Belin

A mystery that will baffle historians a century from now is how a fast-talking New Yorker like Donald Trump could win Iowa’s six electoral votes by with a 9.4 percentage point margin over Hillary Clinton despite losing six of Iowa’s most populous counties.

Trump was called a “populist,” which would have surprised original 19th century populists such as Andrew Jackson and William Jennings Bryan, who at least lived in the outlier states of Tennessee and Nebraska and faithfully represented the values of their regions.

But despite a near-total lack of connections and experience with Iowa, Trump overcame Clinton’s margins in Scott, Polk, Story, Linn, Black Hawk, Johnson, and Scott counties to win big in rural counties. Trump’s politics of resentment played well in non-urban Iowa, beset by losses of population, schools and businesses, rising drug and crime problems, and a feeling of being culturally denigrated by Clinton and the coastal-dominated political and media elites.

Trump also benefitted from a slumping Iowa agricultural economy in 2016, which tends to work in favor of challengers. But there lies the rub for President 45; the Iowa farm economy has slid even further on his watch. As farmers take to the fields to plant this month, troubling numbers are coming from all sides as the effects of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and the trade war on agriculture are tallied.

Corn, soybean, and hog prices have fallen to fifteen-year lows since the beginning of the year. Corn exports are their lowest since 2013 and soybean exports, which have been virtually shut down during Trump’s trade war, are at their lowest levels since 2004. Hog prices have dropped from around 90 cents per pound at the beginning of 2020 to 46 cents per pound last week, a decline that costs producers around $1,400 per animal. Ethanol prices are down from $1.30 per gallon at the beginning of 2020 to 93 cents this week, a casualty of the worldwide oil glut. Several Iowa ethanol plants have closed or reduced production in the last month.

The first serious crunch of those numbers by the Iowa State University Center for Agriculture and Rural Development turned up some sobering conclusions. Chief among them was an estimate of losses to Iowa’s agriculture sector of “roughly $788 million for corn, $213 million for soybean, over $2.5 billion for ethanol, $658 million for fed cattle, $34 million for calves and feeder cattle, and $2.1 billion for hogs.” The economists noted that those losses are likely to widen as farmers and livestock producers advance further into the teeth of their marketing year.

Iowa is the nation’s largest hog producing state, and pork production and processing contributes up to $60 billion to the state’s economy. The ISU report predicted,

The industry was already in poor economic shape and cannot handle losses of this magnitude. It is possible that several large integrators will enter bankruptcy and default on rental payments to contract producers. These contract producers are typically heavily leveraged and will default on loans used [to] build the barns.

The most rhetorically alarming part of the report was in the conclusion, where economists noted that unlike previous economic downturns, the coronavirus impact would be felt across the board. For historic precedents, the ISU team wrote, “The large scale destruction of farmland and processing facilities in the Southern United States during the Civil War and the dustbowl on the Great Plains in the 1930s may be the closest analogies.”

Predictive comparisons to the grimmest scenes from Gone With the Wind or The Grapes of Wrath were startling coming from low-key economists not known for throwing hyperbole and metaphors around carelessly.

Another equally troubling analogy was raised last week by Howard Roth of Wisconsin, president of the Urbandale-based National Pork Producers Council, who told a media conference call that hard-pressed hog producers “may be talking about euthanization.” The notion of killing pigs instead of taking them to market conjures up one of the darkest images of the Great Depression in the 1930s, when desperate farmers shot thousands of hogs in Iowa because they could bring no more than 5 cents per pound at market. To his dying day U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace, himself an Iowan, endured the taunt of “baby pig killer.”

The closedowns of pork processing plants at Columbus Junction, Iowa and Sioux Falls, S.D., would seem to point to an eventual price-raising shortage of pork. But according to USDA figures, supplies of frozen pork and record inventories of hogs still on the farms preclude any short-term meat shortages.

The problem for Iowa is on the demand side. Glynn Tonsor, extension specialist at Kansas State University, said last week that demand for meat is “extra-sensitive” to the kind of overall economic pressures imposed by the coronavirus shutdown, adding that “U.S. meat demand is good during stronger economic times and weaker during poor economic times.”

Those economic numbers touch politics most at the level of farm income. Average Iowa farm income stood at a healthy $172,500 in 2012 and was no small factor in Iowans’ willingness to vote for a second term for Barack Obama. By 2016, that average farm income figure had slipped to $97,300, a decline that made farmers more willing to listen to a loudmouth New Yorker like Trump.

This year, the USDA expects average farm income to be no more than $57,500. Despite getting a share of $28 billion in federal funds to ease the impact of lost soybean exports to China destroyed in Trump’s trade war, Iowa recorded 595 farm bankruptcies last year, the highest level since the “Great Recession” year of 2008.

Those numbers and reports are bound to make both the White House and U.S. Senator Joni Ernst very wary this year as they approach Iowa and its appellation as a “battleground state.” Democrats can take hope from recent history. Beginning with the farm crisis year of 1988, Democrats have carried Iowa six presidential elections, one more than they won in the century and a quarter from Abraham Lincoln’s victory in the state in 1860 into the 1980s.

Trump’s victory in 2016, fueled in large part by social issues such as abortion, guns, anti-homosexuality and anti-feminism, reminded historians of the era of Republican domination of Iowa from 1860 to 1932. In that earlier time the great social issues were Iowa’s connection to the memory of Abraham Lincoln (aided by the marriage of Robert Todd Lincoln to a daughter of Iowa Senator James Harlan) and the Union cause in the Civil War and the bolting of the temperance movement onto the Republican Party in liquor-wary Iowa. Those twin tower issues provided a powerful engine for Republicans that Democrats couldn’t overcome even through hard economic times for farmers in the late 1800s.

But beginning with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Depression-era victories in Iowa in 1932 and 1936, Iowans seemed to pay more attention to their economic well-being. Republicans regained their upper hand in the prosperous World War II and postwar years after 1936 until a second farm crisis enabled Bostonian Michael Dukakis to win Iowa convincingly in 1988. Since then Bill Clinton (twice), Al Gore, and Barack Obama (twice again) carried Iowa, and the state’s progressives could feel that Iowa had belatedly taken its place alongside Minnesota and Wisconsin among solid agrarian Democratic states.

Then came Trump.

One can argue whether Trump has truly Made America Great Again, or Drained the Swamp, or even made any great deals abroad since he was sworn in 40 months ago. But Trump and U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue have been spectacularly unsuccessful in improving the fortunes of Iowa’s farmers.

The big problem Trump and Perdue can’t solve is that instead of feeding the world, as Iowa’s farmers like to boast, the world has learned to feed itself. Two decades ago, the U.S share of world corn and soybean export markets approached 70 percent. Buying nations had no real alternative.

Today, U.S. corn sales are still number one in the world, but at a lower market share of 38 percent. Brazil and Argentina together now account for 25 percent of the world market (and growing). Former communist nations Russia, Ukraine, Romania, and Poland, who begged the U.S. for grain sales in the darkest days of the Cold War, now account for ten percent of the world export market. Even India is an occasional, albeit small, corn exporter.

Trump’s trade war with China can’t be held as the prime reason for America’s loss of its number one soybean export position to Brazil, but the scrap probably means that Iowa’s farmers are unlikely to regain their top spot in the foreseeable future.

The inconvenient truth about Trump’s China trade deal is that it legally obligates China to do nothing, despite Trump’s loud proclamations that China would purchase “billions” of dollars of U.S. farm products. When he signed the Chinese trade deal, Trump boasted that “farmers will need to buy bigger tractors.” But this week, at a White House press briefing, the president made a revealing comment when he let slip, “So we ended up signing a very good trade deal. Now I want to see if China lives up to it. I know President Xi, I think he will live up to it. If he doesn’t live up to it, that will be okay too because we have very, very good alternatives.”

Trump didn’t say what those “very good alternatives” might be, but they had better be pretty big. At its peak, the U.S.-China soybean trade consumed 60 percent of American soybean exports.

The commodity markets are skeptical. This week the futures price for the November, 2021 soybean contract stood at $8.51 per bushel, hardly a sign that traders expect a huge influx of export sales for American soybean farmers.

Whether Iowa’s 85,000 farm operators and the larger number of people who live in small towns or work in the state’s agribusiness complex that includes manufacturing, processing, seed production, insurance, and trading hold Trump to his bombastic promises for the farm economy is open to question. In the coming campaign, Trump and his spokespeople can be expected to fall back on the rural standby issues, abortion and gun rights, that steer the political argument in much of non-urban Iowa as temperance did more than a century ago.

But the city folks vote too. Iowa’s urban dwellers may be less open to the right-wing social issue message, but they still have connections to agriculture through their jobs, extended family ownerships of a farm they left years ago, or simply an interest in the economic well-being of the state. Blue collar workers at Deere & Co., Kimze, Vermeer and other farm manufacturers who were led astray from their Democratic moorings by Trump in 2016 might be jolted back into their traditional Democratic fold by layoff notices.

The late (and moderate “centrist”) Governor Robert Ray was a Republican political powerhouse during his era as the state’s chief executive from 1969 to 1983. But Ray had to overcome the stigma of being a “Des Moines lawyer” with the farmers and small town folks who have long been the bulwark of Iowa’s Republican battleship. He found a unique way to do it.

“I always start the day by looking at the price of corn in the paper,” Ray told me in the pre-internet days of the 1970s. “If the price is strong and holding, I know that people will at least be in a pretty upbeat mood. If the price is going down, I know that I’ll have to work harder to make people feel good about things.”

Dan Piller was a business reporter for more than four decades, working for the Des Moines Register and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. He covered and oil and gas industry while in Texas and was the Register’s agriculture reporter before his retirement in 2013. He lives in Urbandale.

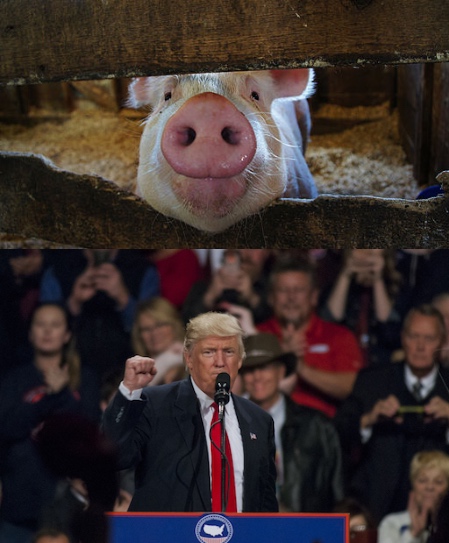

Top image: At top, “Iowa pig” photo by Steve Evans, available via Wikimedia Commons. At bottom, Mark Reinstein’s photo of President-elect Donald Trump at a victory rally in Des Moines on December 8, 2016, available via Shutterstock.

3 Comments

Insightful!

A very insightful analysis. One criticism that can be levelled at the Democrats is that they don’t make Trump’s agricultural failures as clear to voters as they could.

JeffDC Thu 16 Apr 3:24 PM

And with everything else that is going on...

…it’s likely that little attention will be paid in 2020 to the massive water degradation caused by Iowa industrial agriculture when yet another gigantic flush of nutrient pollution heads downstream to grow the Gulf dead zone later this year. Sorry, Louisiana, Iowa is a truly rotten upstream neighbor, and the people in charge here don’t care. And judging from their actions, as opposed to their organizational PR, many landowners and farmers don’t care either, and didn’t care even when the farm economy was a whole lot better.

PrairieFan Thu 16 Apr 4:14 PM

Hog prices

I think a decimal point must have strayed in the comment about hog prices. They have never been worth $1400 each, let alone seen a price decline of $1400.

iowavoter Fri 17 Apr 8:58 AM