For the first time on April 14, the Iowa Department of Public Health released information about novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infections by race and ethnicity. The results won’t surprise anyone who has been following the news from other parts of the country: a disproportionate number of Iowans with confirmed COVID-19 infections are African American or Latino.

Activists and some Democratic legislators had pushed for releasing the demographic information after a senior official said last week the public health department had no plans to publish a racial breakdown of Iowa’s COVID-19 numbers.

Meanwhile, Iowa reported its largest daily number of new COVID-19 cases (189) on April 14, fueled by the outbreak that has temporarily shut down a Tyson pork processing plant in Columbus Junction (Louisa County). At her daily press conference, Governor Kim Reynolds again praised efforts by meatpacking companies to slow the spread of the virus and keep workers and the food supply chain safe. However, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) has highlighted unsafe workplace conditions for employees of meatpacking plants, a group that is disproportionately Latino.

AFRICAN-AMERICAN, LATINO IOWANS MORE LIKELY TO HAVE COVID-19 DIAGNOSIS

The state’s new website for COVID-19 information published the following data in the “demographics” section on April 14.

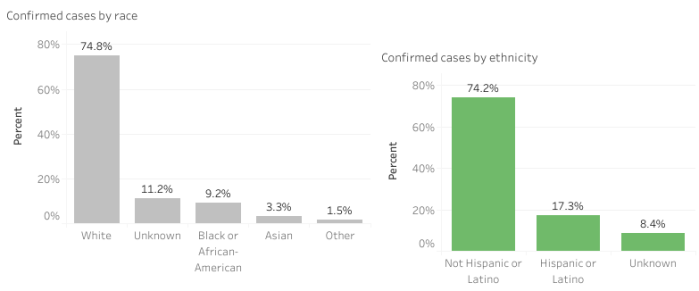

According to U.S. Census Bureau estimates from July 2019, 4.0 percent of Iowa’s residents are African-American, and 6.2 percent are Hispanic or Latino. Among Iowans confirmed to have coronavirus infections, 8.7 percent are African-American, more than twice that group’s share of the overall population. Some 16.4 percent are Latino, more than double that group’s share of the population.

The department has not yet released a racial breakdown of Iowa deaths from coronavirus.

UPDATE: Numbers released on April 15 show larger disparities: African Americans represent 9.2 percent of confirmed cases in Iowa, and Latinos make up 17.3 percent.

LATER UPDATE: As of April 17, African Americans represent 9.0 percent of confirmed cases, Latinos 17.9 percent, and Asians 3.9 percent. Approximately 2.6 percent of Iowans are Asian, and many immigrants from Asia work in meatpacking plants.

People of color have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19 for many reasons. A letter to the governor from leaders of the Iowa-Nebraska NAACP Conference observed that African Americans are less likely to own their own homes, making social distancing more difficult. They are also less likely to be able to work from home, since many hold jobs in “essential” sectors like health care and the food supply chain.

During an April 14 online press conference, LULAC’s national president, Domingo Garcia, mentioned that Latinos are more likely to lack health insurance and often have many family members living in the same household, which facilitates community spread of the virus. Garcia also noted Latinos are also dying at higher rates than others infected with COVID-19. Many have underlying health conditions like diabetes, which raise the risk of life-threatening complications.

LULAC’s leading voice in Iowa, Joe Henry, commented at the same news conference that Latinos make up a large share of the workforce in meatpacking plants, and that an estimated three out of every four agricultural workers across the country “are from our community.”

“THAT’S NOT SOMETHING THAT WE PLAN TO RELEASE”

Iowa was not initially among the states releasing COVID-19 data by race. At the governor’s April 7 news conference, one of the reporters asked why those numbers were not available.

Iowa Department of Public Health Deputy Director Sarah Reisetter indicated the department had no plans to release case counts by race and ethnicity. She speculated that such demographic information might be made public later, as part of “an outbreak investigation report” that is compiled at the end of every infectious disease outbreak. Reisetter added,

At this point in time, the way that the information is collected by the department, we don’t have statistics that I think we would consider to be accurate and complete related to some of that race and ethnicity information. So that’s not something that we plan to release at this particular point in time.

The answer made little sense. Hospitals and county public health departments routinely collect information about patients’ race and ethnicity. State Medical Director and Epidemiologist Dr. Caitlin Pedati had already ordered hospitals to report daily on various numbers related to COVID-19 cases. Why not also require them to report the race and ethnicity of patients being treated for coronavirus?

The pushback was immediate.

“WHEN AMERICA SNEEZES, THE BLACK COMMUNITY CATCHES PNEUMONIA”

Betty Andrews, president of the Iowa-Nebraska NAACP conference, and Jacquie Easley McGhee, the health chair for the conference, wrote to Reynolds on April 9. Excerpts from their letter, published in full at the end of this post:

A common saying in the African American Community is “When America sneezes, the Black community catches pneumonia.” The expression signifies that when crisis hits our country, it hits the African American Community with even more devastation. As you may be aware, emerging data across the country is showing that African Americans have been impacted by the COVID-19 crisis at significantly higher levels than white people. They are more likely to be affected and to succumb to this illness. They face the challenges of access to testing in their communities; and because of the disparities in risk factors such as diabetes and heart disease, they are more likely to experience the severest brunt of the virus.

As President and State Health Chair of the Iowa NAACP – a strong voice in the African American Community, and representing branches across this state, we write to request (1) that racial data and disparities be tracked, monitored, and considered in the State’s decision-making processes and (2) that our State Government take careful and deliberate measures to close any gaps in the availability of health care, the economic impact of the crisis, education resources and other measures on account of the COVID-19 Pandemic. We also request that this data be made available for public access through electronic means.

Andrews and Easley McGhee added, “data delineated by race is a critical part of tracking the pathology of a disease and will also provide vital information on how to address future crises of this nature (God forbid).”

The NAACP leaders urged Reynolds and state agency directors “to pay close attention” to how coronavirus and the associated economic disruption may be disparately affecting Iowans of color in many other areas, such as educational opportunities, assistance for struggling small businesses, and criminal justice. They directed the governor’s attention to several national news reports about COVID-19 and racial disparities, as well as Dr. Anthony Fauci’s recent remarks on health disparities in the African-American community.

Finally, Andrews and Easley McGhee offered to set up “a videoconference call with representatives from communities of color to talk about the importance of monitoring race during this pandemic and how to effectively consider it and address the concerns about disparate impact.”

In an April 14 telephone interview, Andrews told Bleeding Heartland early signs of racial disparities in the COVID-19 crisis were “disappointing” but not “shocking.” She said the numbers “highlight the reason to work on the disparities” in health care and many areas of life when there is no crisis.

The usual “stress that comes from being part of a vulnerable community” is heightened in a pandemic that has the potential to “decimate” African Americans, Andrews said. She emphasized, “This is the beginning.” Even after the first wave of infections passes, African Americans will be hit harder during the economic recovery, due to unequal access to resources. The NAACP will closely follow those issues.

Others who pushed the Iowa Department of Public Health to release demographic data include Democratic State Senators Joe Bolkcom and Zach Wahls. After the first numbers were released on April 14, they told Bleeding Heartland, “We are happy that IDPH has decided to publicly share a comprehensive set of data on people that are testing positive for COVID 19. Governor Reynolds needs to continue to be transparent about the on-going impacts of the coronavirus on Iowans and efforts to combat it.”

REYNOLDS DEFENDS MEATPACKERS’ STEPS TO CONTAIN COVID-19

Meatpacking plants in many states have become hotspots for COVID-19, due to the large number of employees working in close proximity to one another. The outbreak at the Tyson plant in Columbus Junction made Louisa County (with 145 confirmed cases in a population around 11,000) Iowa’s worst for COVID-19 infections per capita. Of the 189 new COVID-19 cases the state announced on April 14, 86 were linked to the Tyson plant.

LULAC filed an Iowa Workforce Development OSHA complaint on April 1, citing meatpacking plants including JBS in Marshalltown. Lana Bradstream reported for the Marshalltown Times-Republican at that time,

LULAC Council No. 307 president Joe Henry said the company is not protecting workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The hazard description described in the complaint, numbered 31976862, states that unsafe working conditions at the JBS in Marshalltown exist in cutting, processing, break and dressing rooms. The complaint further states JBS employs 2,700 people in Marshalltown “who work shoulder to shoulder in most of the meat cutting and processing department rooms at the facility.”

Donnelle Eller reported for the Des Moines Register on March 31,

JBS and other meat processing companies with large plants in Iowa say they’re taking action to protect workers, including checking their temperatures and looking for other symptoms of the coronavirus before employees enter plants; staggering shifts and breaks; and providing more space for workers on the production floor and in break rooms.

Reynolds told reporters on April 7 that “she has been speaking with the CEOs of Iowa packing plants.” O.Kay Henderson reported for Radio Iowa,

“They are always taking precautions and now extra precautions to make sure that the food supply chain is safe,” Reynolds said.

Employees at the pork processing plant in Columbus Junction and the beef processing plant in Tama have tested positive for COVID-19 and both plants temporarily shut down for deep cleaning. Reynolds said state officials have recommended packing plant managers take several steps in the midst of this pandemic — like taking the temperature of all employees before every shift, to screen out those who may have a fever.

“Making sure that their employees know that if they’re sick, stay home. If anybody in their household is sick, to stay home,” Reynolds said. “If they’re experiencing any of the symptoms (of COVID-19) to call the doctor, go through the assessment.”

At her latest press conference, Reynolds said of Tyson, “They have really been very proactive in making sure what when they stand the plant back up, they are doing everything they can not just to protect the employees but to continue a really critical part of our food supply chain.” Asked whether the state will weigh in on reopening the plants, the governor said the companies are “making those decisions.”

“WE CAN’T SURVIVE WITH THESE PLASTIC SHEETS”

Speaking at LULAC’s April 14 news conference, Henry offered a different picture of safety measures in meatpacking plants. LULAC is hearing from workers in many parts of the country about unsafe conditions, he said. “Smithfield seems to be the one right now that’s having a difficult time catching up.”

Smithfield’s pork processing plant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota recently shut down because of a large COVID-19 outbreak. Its 3,700 employees include some in northwest Iowa. Henry said some employees at Smithfield’s plant in Denison (Crawford County) have expressed concerns about that workplace.

Meatpacking companies need to take further action, Henry added, such as installing plexiglass between workers. “Right now plastic sheets are the only things that are being dropped in between the workers within inches of each other.” LULAC is hearing from workers, “We need safe distance between each other in the cutting rooms. We can’t survive with these plastic sheets.”

LULAC also wants meatpackers to reduce the number of workers on each shift. It’s impossible to maintain a safe distance from others when, for example, fifteen women might need to crowd into a small restroom during a five-minute bathroom break, Henry told reporters.

In a statement provided to Bleeding Heartland later the same day, Henry said,

Latinos and immigrants are working in agriculture and all levels of food production, and in warehouses and other industries where people work within inches of each other but little to no safety standards have been implemented to safeguard against infectious diseases, such as COVID-19. LULAC filed an OSHA complaint recently on April 1st against Iowa meat processing companies that have violated health and safety standards and we are awaiting a decision.

Furthermore the State of Iowa continues to publish official documents only in English which restrict the rights of Spanish speaking Latinos and other non English speaking communities from accessing information about enforcing safety standards in the workplace and how to apply for unemployment benefits. All of these roadblocks have led to increase illnesses and infections for communities of color.

The state that feeds the world in pork and corn has also fostered a poisonous environment for Latinos and immigrants. Shame on our elected officials and the governor!

Publishing demographic data is an important step toward understanding the impact of COVID-19, but the state must do much more to mitigate the harm done to communities of color.

UPDATE: During the governor’s April 15 news conference, Deputy Director Reisetter said the department is working on providing instructional materials in alternate languages and reaching out to businesses that employ large numbers of high-risk Iowans.

_____________________________

Appendix: Full text of April 9 letter to Governor Kim Reynolds from the Betty Andrews, president of the Iowa-Nebraska NAACP conference, and Jacquie Easley McGhee, the State Area Health Chair for the Iowa-Nebraska conference