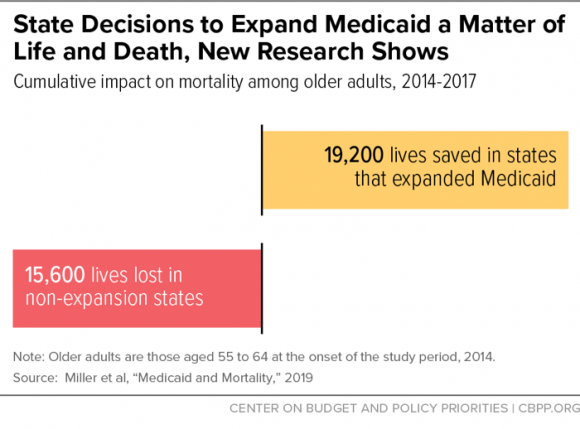

Expanding Medicaid “saved the lives of at least 19,200 adults aged 55 to 64” during the four years after the Affordable Care Act went into effect, including an estimated 272 Iowans, according to a new paper by Matt Broaddus and Aviva Aron-Dine for the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Conversely, 15,600 older adults died prematurely because of state decisions not to expand Medicaid. […] The lifesaving impacts of Medicaid expansion are large: an estimated 39 to 64 percent reduction in annual mortality rates for older adults gaining coverage.

Broaddus and Aron-Dine drew on a peer-reviewed study by Sarah Miller, Sean Altekruse, Norman Johnson, and Laura Wherry, who compared “mortality rates among 55- to 64-year-olds likely eligible for Medicaid in expansion states to mortality rates among similar older adults in non-expansion states.”

Prior to Medicaid expansion, the study finds, mortality trends among low-income older adults were similar in states that would and would not later expand Medicaid. But they sharply diverged starting in 2014, the first year of expansion. In 2014 the annual mortality rate for low-income older adults in expansion states fell by about 9 deaths per 10,000 people, compared to similar adults in non-expansion states, with the impact growing each year to about 21 deaths per 10,000 people in year 4.[6] (See Figure 2.) These differences amount to about 19,200 lives saved among older adults in expansion states over four years, and about 15,600 lives lost among older adults in states choosing not to expand. By 2017 the annual impact is more than 7,000 lives saved in expansion states and almost 6,000 lives lost in non-expansion states.[7]

To confirm that access to care through Medicaid was responsible for saving lives, as opposed to some other factor, the researchers “examine mortality trends in expansion and non-expansion states for people over 65, a group that was not affected by Medicaid expansion (since they already had coverage through Medicare).” They found “no divergence in mortality rates for seniors between expansion and non-expansion states in 2014.”

The authors also demonstrate that the mortality reductions were driven by reductions in deaths from “health-care-amenable” causes such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and kidney disease, conditions known to be responsive to medical care.

Broaddus and Aron-Dine linked to numerous previous studies, which pointed to life-saving impacts from Medicaid expansion. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities created this infographic to summarize those conclusions.

Miller and Wherry calculated state-level mortality estimates “based on an estimate of the average effect of the ACA Medicaid expansions among all expansion states.” They reckon that in Iowa, 68 deaths among people between the ages of 55 and 64 have been averted every year from 2014 through 2017. That works out to 272 on the table compiled by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which lists the four-year estimates for each state.

If Republicans had controlled state government in the early part of this decade, Iowa would likely never have expanded Medicaid. The Democratic majority in the Iowa Senate insisted on a version of Medicaid expansion during the 2013 legislative session, as part of a grand bargain that also included a large commercial property tax cut and eliminating most oversight of homeschoolers.

Governor Terry Branstad wasn’t interested in expanding Medicaid, but he desperately wanted the property tax cut. That cut did little for the economy and proved to be very costly. In subsequent years, it contributed greatly to state budget crunches and underfunding of education, among other priorities. But arguably the trade-off was worthwhile. Some 150,000 Iowans gained access to a version of Medicaid, and hundreds are alive today because of it.

The real number may be larger than 272, as this study looked only at people between the ages of 55 and 64. Many younger Medicaid recipients could have received life-saving preventive care (such as cancer screenings) or services to treat chronic medical conditions, mental health issues, or addiction.

Other research Broaddus highlighted on November 6 indicates that Medicaid expansion states “saw both larger coverage gains and larger drops in uncompensated care: a 55 percent fall in uncompensated care costs on average compared to an 18 percent fall in states that did not expand Medicaid.” Those data show Iowa’s uninsured rate (which was among the lowest in the country even before the Affordable Care Act) dropped by 47 percent between 2013 and 2016. Uncompensated care as a share of Iowa hospital budgets dropped by 51 percent during the same period.

Americans newly covered through Medicaid received other collateral benefits as well. Aron-Dine flagged a study recently published in the National Journal of Public Health, which found that home “evictions fell about 20 percent in expansion compared to non-expansion states.”

Top image: Figure 1 from a November 6 report for the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Medicaid Expansion Has Saved at Least 19,000 Lives, New Research Finds.”