For weeks this fall, the Iowa Department of Human Services stonewalled a journalist’s request for easily accessible public records that would have cast an unflattering light on management of the state’s Medicaid program.

Three days after Governor Kim Reynolds won the election, the department sent a copy of one key document to Ryan Foley of the Associated Press. DHS released other relevant files on December 6, allowing Foley to confirm Director Jerry Foxhoven had cut a deal in April allowing UnityPoint Health affiliates to keep nearly $2.4 million they had been overpaid for services provided to Medicaid patients.

The settlement agreement came shortly after UnityPoint agreed to remain part of the network for Amerigroup, one of the private companies DHS picked to manage care for Medicaid recipients.

“A $2.4 MILLION DECISION TO BENEFIT ONE PROVIDER NETWORK”

UnityPoint had warned in November 2017 that it might pull out of Amerigroup’s network. Doing so would have disrupted care for some 54,000 Iowans on Medicaid, who use UnityPoint’s hospitals or clinics in more than a dozen Iowa metro areas.

The governor frequently asserted in 2017 and early 2018 that “modernized” Medicaid was serving patients well. Tens of thousands of Iowans losing access to specialists or primary care physicians would have undermined that narrative. So it was a “political victory for Reynolds” when UnityPoint and Amerigroup found common ground shortly before an April 1 deadline, Foley noted in his December 6 story for the AP.

Foxhoven signed a settlement agreement with a UnityPoint vice president on April 25, allowing some of the twelve hospitals affiliated with the medical group to repay substantially less than the amount they had received in excess.

From Foley’s report:

A whistleblower alleged in a letter to Democratic state Sen. Joe Bolkcom that the agreement was payback for UnityPoint’s continued participation in Medicaid.

In an interview Thursday, Bolkcom said administration officials never informed lawmakers “that they made a $2.4 million decision to benefit one provider network” and questioned whether they had the authority to waive the collection of documented overpayments. He suggested the incoming state auditor, Democrat Rob Sand, should investigate the deal as part of his promised review of Medicaid.

“This just looks really fishy that this deal would be struck,” Bolkcom said. “It would appear this was done to alleviate this political problem of a big provider literally dropping out of the managed care network.”

Speaking of alleviating political problems, the DHS stalled its response to Foley long enough to avoid bad headlines about the UnityPoint deal shortly before the election.

“RECORDS MUST BE PROVIDED PROMPTLY”

Near the end of his story, Foley mentioned,

The AP requested a copy of the settlement agreement from DHS in early October. At the time, Medicaid was a central issue in the governor’s campaign against Democrat Fred Hubbell, who had accused her of mismanaging the program and ran television ads highlighting the impact on the disabled.

DHS released a copy on Nov. 9, days after Reynolds narrowly defeated Hubbell to win a four-year term. Additional records were released Thursday [December 6] confirming UnityPoint’s affiliates paid back $2 million earlier this year but an additional $2.4 million was waived.

I requested the same records from DHS on December 7 and received electronic copies in less than two hours. You can find links to all of the documents at the end of this post. Here is the file containing the two-and-a-half-page settlement agreement and three unrelated e-mails.

It could not have taken DHS officials more than a few minutes to locate the settlement agreement. Yet they did not turn it over for at least four weeks. A monthlong delay might be understandable for a request that brought up hundreds or thousands of pages of responsive documents, but that wasn’t the case here.

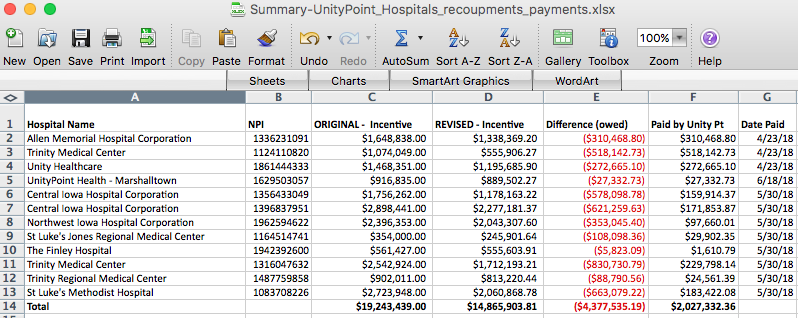

The files produced on December 6 were not voluminous either: twelve short letters and this spreadsheet (xls file) showing recoupment payments by UnityPoint hospitals. A screenshot of its contents:

Iowa’s open records law (Chapter 22) does not specify a deadline for providing documents, but the Iowa Supreme Court unanimously held in 2013 that “our legislature contemplated immediate access to public records.” That ruling, authored by Justice Edward Mansfield, cited a “longstanding administrative interpretation” of Chapter 22, dating to 1985:

Access to an open record shall be provided promptly upon request unless the size or nature of the request makes prompt access infeasible. If the size or nature of the request for access to an open record requires time for compliance, the custodian shall comply with the request as soon as feasible.

The high court went on to say, “practical considerations can enter into the time required for responding to an open records request, including ‘the size or nature of the request.’ But the records must be provided promptly, unless the size or nature of the request makes that infeasible.”

The Iowa Public Information Board, which is charged with enforcing state law on open meetings and open records, issued an advisory opinion in 2014 echoing the Supreme Court’s determination: “Access to an open record shall be provided promptly upon request unless the size or nature of the request makes prompt access infeasible. If the size or nature of the request for access to an open record requires time for compliance, the custodian shall comply with the request as soon as feasible.”

The DHS is not the only government agency to withhold public records long enough to diminish the news value. Nor is the agency’s bad-faith approach to Chapter 22 requests a new phenomenon. Under Foxhoven’s predecessor, Director Chuck Palmer, the DHS refused to provide video footage of an alleged assault by a worker at the Iowa Juvenile Home–even though the department had previously disclosed “a recording from the same type of equipment at the same state facility.”

Last year, the DHS took more than five months to cough up actuarial reports on Medicaid requested by Des Moines Register investigative reporter Jason Clayworth.

This February, the agency admitted its delay “was not appropriate” or consistent with state law and took several steps to resolve Clayworth’s subsequent complaint to the Iowa Public Information Board. Among other things, DHS “reviewed and revised its internal policies and procedures for responding to requests for public records,” setting a goal “for release of public records within 10 business days.” DHS also agreed to “release records as available, even if a portion of the request is still under review or being collected.” (emphasis added)

Under Iowa law and newly-adopted DHS policies, staff should have provided the UnityPoint settlement quickly after a journalist asked to see it. Instead, a costly and irregular arrangement, which one whistleblower characterized as payback for UnityPoint’s willingness to keep doing business with Amerigroup, remained hidden from Iowa voters.

I am seeking further details on how the DHS handled requests for documents about the UnityPoint deal. Stay tuned.

Appendix: Public records the Iowa Department of Human Services provided to the Associated Press in November and December 2018, regarding an agreement to allow UnityPoint affiliates to keep some overpayments for services provided to Medicaid patients.

1 Comment

Payoff

This story should have come out kind before the Gubernatorial election! In the past year I’ve found DHS to be less & less a State entity that has any moral compass as to how they do “business”. I have found them to be corrupt to their very core. Thank you to Ryan Foley & Bleeding Heartland for shining a light on this agency, their unethical (I’ll stop just at criminal) practices extend beyond this cover up & just say that I hope everyone in this State is still outraged about the 2 girls that lost their lives + the large number of families who have been ripped apart by DHS by any means necessary

Sherry Kiskunas Tue 11 Dec 8:30 AM