A provocative idea from Richard Lindgren, emeritus Professor of Business at Graceland University and a past president of the Lamoni Development Corporation in Decatur County. -promoted by desmoinesdem

I have lived in Iowa for almost 20 years of my life in total, over several tenures, and for the life of me, I still can’t understand why the voters of the state allow the degree of governmental centralization that exists in the Des Moines area while so many smaller towns in the state continue to experience demographic and economic decline.

Humor me for a bit and engage with me in a “What If?” exercise. What if all the jobs involved in running the Iowa state government were more equally distributed around the state, say on a per capita basis, or better, weighted to local economic need? In this world of high-tech communication, why does Des Moines, already awash in private and public economic development dollars, continue to hold such a disproportionate share of the jobs required to run the state government? We’ll look at the obstacles in a bit, but we first may need some “whack on the side of the head” re-imagining here.

I have been involved in economic development efforts in south-central Iowa for some time, and I don’t think it would be any surprise to say that it is hard work, especially for the excellent paid development directors we have invested in over the last several years. We have made some good progress in recent years, with some great new small businesses, a new hotel, an excellent, growing community health center and a new county hospital.

But I know some demographic math, and like so many other Iowa communities, the future looks increasingly rough. Left to private enterprise, “non-Des Moines” is becoming the exclusive home of large-scale industrial agriculture, leaving a shrinking number of stable communities in small pockets. While generating an increasing amount of strain on the environment, these businesses support much less of the local community infrastructure, as compared with the past–support that once sustained jobs, families and schools, the very core of what makes Iowa a great place to live. Is there another way?

An example from Norway

Our national pride seems to keep us from looking at how other countries address similar problems, but I ran into an interesting example of industrial policy while traveling through the Norway fjords in 2015. I was on a family trip, meeting the children of relatives who had (wisely, in hindsight?) declined to emigrate to the United States over a century ago. In an unlikely, but beautiful, place called Brønnøysund, a town of only 5,000 people halfway up the 1,000-mile-long Atlantic coast, I came across a large governmental office.

By Bjørn Christian Tørrissen – Own work by uploader, http://bjornfree.com/galleries.html, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

This town had suffered great economic challenges, as did others along this remote coast, with the decline of the fisheries and their related businesses in the 1970s. Even the North Sea oil boom had passed them by. In 1980, the Brønnøysund Register Centre was established to maintain a small set of official government registers, and it now maintains a long list of digital records, most significantly the Register of Business Enterprises. If you set up a legal business or other organization in Norway, this is the office you work with, and it has grown both in size and technology capabilities to service the entire country.

If Norway operated like most of the U.S., this office would certainly be in the capital, Oslo. In the U.S. we replicate these functions at the state level, so here the equivalent office would be (and is) in the Des Moines metro area. But instead, this Norwegian office was part of a coordinated plan to build better roads and communications linking these remote communities, as well as supporting education, using the employment needs of the government to assist local economies outside the capital.

Brønnøysund, Norway – openstreetmaps.org

In 1980, the remoteness of this office would have been a big risk (remember, the internet did not become commercially viable until more than a decade later), and its location was almost certainly a short-term detriment. But as this function of state government has become increasingly automated, its potential has been fulfilled, and it is now a major economic and educational driver for the region.

The pros of decentralization

There is no doubt that the “velocity of money,” the circular re-use of the same salary dollar multiple times before it leaves a community (in this case taxpayer dollars), has long been the driving force behind much of the prosperity in Des Moines. In a “virtuous circle,” this cashflow helped the entire region to attract private enterprise capital and jobs as well.

Fun fact (or not): That new Walmart (and often other new large retail developments) you drive by is likely receiving more money as a percent of top-line sales from government sources in its early years than it is delivering in profit to the stockholders. Walmart has prospered for years on an intentionally-thin 3 percent net profit margin, but sales tax, earnings tax, and property tax rebates totaling greater than this are the now the norm for new commercial development.

I have seen (in a neighboring state) a longstanding Home Depot store and a (now gone) Office Max store pay the full bore of taxes while new and bigger Lowes and Office Depot stores were literally built on an adjacent corner, using huge neighborhood infrastructure and tax incentives. This is where the noble and necessary effort for taxpayer-funded economic development investment turns into a disease, where only the rich get richer. Think of the alternative smaller-town investment that wasn’t done in this case.

Taxpayer dollars that go to Des Moines and don’t come back are “negative virtuous circles,” sapping local investment dollars away from communities. Governmental salaries reinvested in local communities pay for purchases at local businesses, support the local real estate market, and pay teacher salaries at local schools. Tax dollars that leave the smaller towns in Iowa, by the same process, help to kill local business and schools. Decentralization of government services can help reverse that circle.

Iowa has long had a “small town ethic” that has far too often proved more mythical than real in recent years. In short, revitalization of Iowa outside the capital is simply the right thing to do if you believe in Iowa. The alternative is to let more towns die. Yet, we rarely hear this as a key campaign plank.

And like that rural region in Norway (far larger geographically than, say, Iowa’s Decatur County, but with a smaller population), new communications technologies and better transportation infrastructure make small-town living more practically feasible. Small-town, high-tech business is certainly for more feasible than when I established a side consulting business while first teaching in rural southern Iowa in the early 1980s. In the days before the internet, a 1200-baud modem and a CompuServe account allowed me to do technology consulting 75 miles away from the “big city.” Today I have fiber broadband, and before I retired, I would regularly conference in real-time with co-workers in India and Russia from my desk in Lamoni, a blip on the map at the Iowa-Missouri border.

The obstacles to decentralization

The political headwind of entrenched civil service employment is very strong, and very resistant to “Why are you where you are?” questions. The answer is usually little better than the old camp song, “We’re here because we’re here, because we’re here, because we’re here!”

For some reason, relocation of state employees is unheard of, yet in private industry, relocation is commonplace. Indeed, that was a major reason for my multiple entries to, and exits from, Iowa over the years, with two people in a marriage trying to maintain professional credentials and also make a living, taking us as far as living in Europe. I recall well the cultural shock of living just outside London, England, one day, and the next day watching my small-town Iowa Fourth of July parade, having relocated back to Iowa. Living outside the new urban landscape is not to everybody’s taste. But then, many smaller-town Iowans see Des Moines as an unattractive rat race.

Ironically, much of southern Iowa now has an officially-low unemployment rate, despite being among the poorest counties in the state, making it even harder to attract new business despite our position on a major interstate highway (I-35) and with a university that has been releasing many new graduates “into the wild” every year since 1895. The low unemployment rate is a statistical artifact mostly caused by young employable people leaving the area each year, a longstanding trend throughout Iowa outside of Des Moines, long commutes to city jobs, as well as classic under-employment at low wages for the people who remain. But even if we had the chance to attract a 100-person new employer, we might have a hard time filling the jobs, because we have failed to invest in the very towns that made Iowa into one of the best-educated states in the country. Decatur County is far from alone in this regard.

Is the decentralization of government in Iowa a fantasy? Would any candidate for governor ever dare to risk Des Moines votes with a bold plan to revitalize other towns using the power of the tax dollar? Which pieces of “the commons” could and should be re-located?

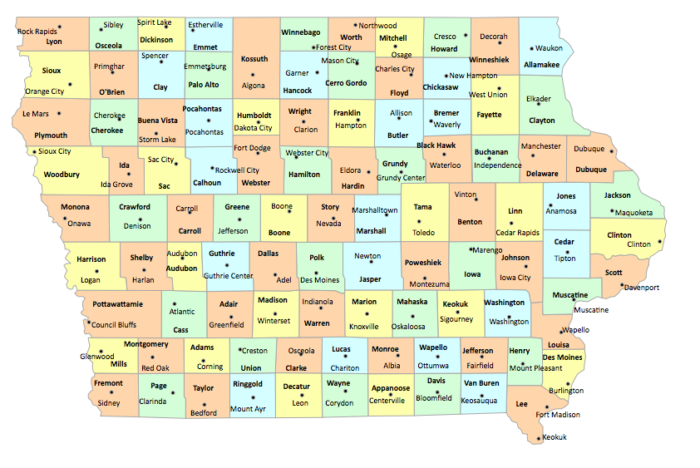

Lease renewals for government offices located in privately-owned buildings come up every year. If you live in Fort Dodge, or Creston, or Keokuk, or Charles City, do you ever ask why those jobs can’t be in your town?

UPDATE: I missed this story from March in the Carroll Daily Times Herald where Fred Hubbell has some concrete ideas on decentralization, although that position does not appear on his campaign website. Perhaps the time has finally come. It’s your choice.

Richard Lindgren is Emeritus Professor of Business at Graceland University in Lamoni, Iowa. A retired CPA, he is a past president of the Lamoni Development Corporation. He blogs at godplaysdice.com.

1 Comment

I think this idea is definitely worth considering...

…and I’d be interested in reading about if/how versions of this idea might be working in other states.

I’d also point out that one reason large-scale industrial agriculture keeps getting bigger, as pointed out above, is because Iowa allows it to externalize costs. I know of one farmer in my township who just laid out $730,000 to buy another eighty acres. Meanwhile, he hasn’t laid out money to put conservation on other land he already owns, land which badly needs grassed waterways and other conservation (cover crops, bioreactor, saturated buffer, something!) to reduce the soil and nitrates that his land is shedding into the nearest creek. And I know his land is shedding N, P, and soil because I monitor that creek.

Rural Iowa could acquire a significant number of jobs from farm conservation work, but not as long as farm conservation in Iowa remains completely optional. Meanwhile, industrial-ag groups are working overtime to spin, lie, and mislead the public about the “progress” Iowa is making on water quality. I’m guessing that spin work is mostly done in cities.

PrairieFan Thu 12 Jul 9:53 AM