Some surprising news arrived in the mail recently. In response to one of my records requests, Governor Kim Reynolds’ legal counsel Colin Smith informed me that “zero dollars” of a $150,000 appropriation for gubernatorial transition expenses “have been spent and there are no plans to spend any of that appropriated money.” I soon learned that the Department of Management had ordered a transfer of up to $40,000 in unspent Department of Revenue funds from the last fiscal year “to the Governor’s/Lt. Governor’s General Office to cover additional expenses associated with the gubernatorial transition.”

A Des Moines Register headline put a favorable spin on the story: “Reynolds pares back spending on office transition from lieutenant governor.” However, neither the governor’s office nor Republican lawmakers ever released documents showing how costs associated with the step up for Reynolds could have reached $150,000.

Currently available information raises questions about whether Branstad/Reynolds officials ever expected to spend that money, or whether they belatedly requested the fiscal year 2018 appropriation with a different political purpose in mind.

STRANGE TIMING

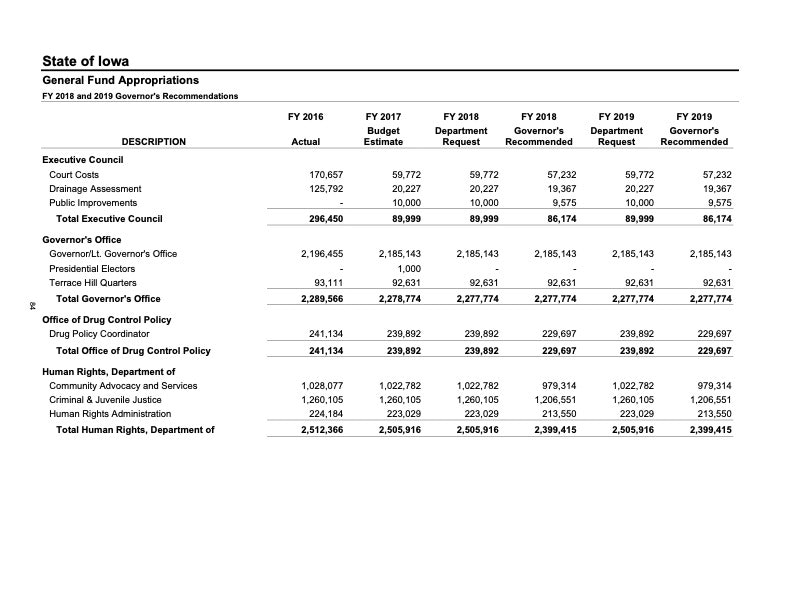

Branstad accepted President-elect Donald Trump’s offer to become U.S. ambassador to China in early December, setting the stage for the transfer of power to Reynolds. Yet the governor’s draft budget, submitted to state lawmakers on January 10, doesn’t include any line item for gubernatorial transition expenses. Here’s the page showing appropriations for the governor’s office:

Iowa’s Revenue Estimating Conference revised projected revenues downward on March 14. For fiscal year 2018, the new estimate was $191 million lower.

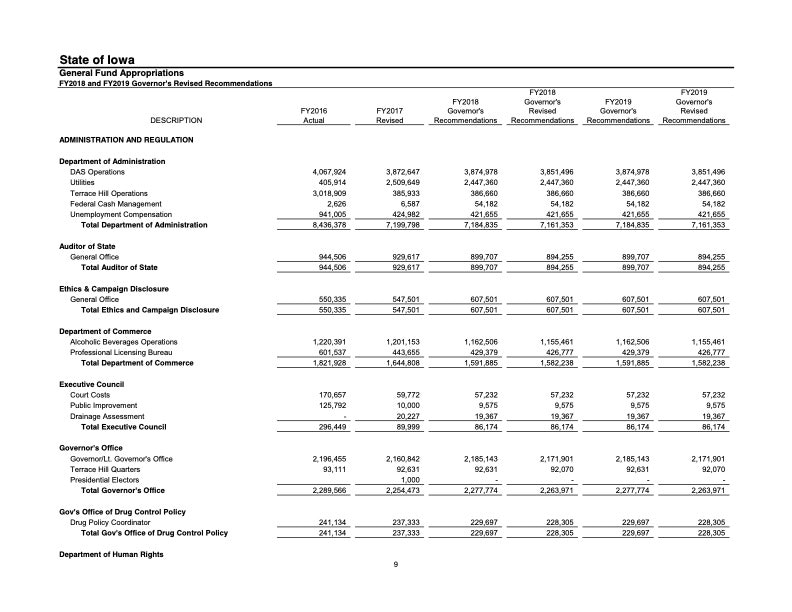

As a result, the Department of Management sent state lawmakers new spending recommendations from Branstad on March 28. As with the governor’s initial draft, this document lacks any line item for gubernatorial transition expenses.

Exactly when the governor’s office requested the $150,000 appropriation is not clear. Iowa Senate Appropriations Committee Chair Charles Schneider declined to answer that question directly in e-mail correspondence this week. The public and Democratic lawmakers first learned about the plan when the final spending bill was published on April 18. Better known as the “standings bill,” Senate File 516 included $150,000 “for expenses incurred during the gubernatorial transition.”

Democratic State Senators Tod Bowman and Kevin Kinney offered an amendment striking the appropriation. During the April 20 floor debate on that amendment, Bowman argued, “While the state’s in the middle of a budget mess, it’s extravagant and unnecessary to spend $150,000 to move the lieutenant governor from one room of the Capitol to the other.” Fellow Democrat Matt McCoy called the spending “wasteful.”

Schneider countered that Iowa lawmakers had approved spending $170,000 for the transition from Governor Tom Vilsack’s to Chet Culver’s administration in 2007. For that reason, “this does not seem to be an unreasonable request. And when we asked the governor’s office why they thought this was reasonable, they stated that there are certain expenses they know they will need to incur,” such as cashing out vacation time and sick time for Branstad staffers who do not continue working for Reynolds. Republican State Senator Mark Chelgren cited the legislature’s “responsibility to fund and to trust” other branches of government, saying “it’s only fair” for lawmakers to grant what he called “a reasonable request” by the executive, “in deference to their position as one of those coequal branches of government.”

Here’s the relevant clip, which I pulled from the Iowa Senate’s video archive (beginning around the 2:26:00 mark).

Branstad was visibly angry when asked about the controversy at his April 24 press conference. William Petroski reported for the Des Moines Register at the time,

“Listen, those liberal Democrats have nothing to talk about here. I tell you, I can’t believe it,” Branstad said. “They would criticize a Republican woman, but they would give $170,000 to a Democrat male.”

Branstad added that the transition involves a lot more than simply moving from one office to another. The new governor has an opportunity to review all departments and agencies, he said. In addition, some longtime employees leave when a new governor takes office and a “huge payout” is required to cover their unused vacation time, he said. However, Democrats said they don’t expect much turnover when Branstad resigns as governor and it’s unlikely much will change in state government because Reynolds has been part of Branstad’s administration since early 2011.

Branstad also said the costs of operating the governor’s office have been reduced since he returned as governor more than six years ago. A Branstad aide said the office now spends about $2.1 million annually compared to $2.3 million in 2011.

Reynolds chimed in to agree with Branstad as he talked to reporters, saying, “The bottom line is that it (the office budget) is lower than when we took office in 2011.”

Branstad added, “That shows that we have cut the size of the staff. We have been very frugal. We have reduced the size and cost of government. We have a smaller and smarter government than we inherited. We are proud of that, but there is no reason why Kim Reynolds should be denied the same transition that other governors have received.”

If that’s the case, why didn’t Branstad ask for transition funds as part of his original draft budget for fiscal year 2018, or with his revised recommendations from March 28?

REQUESTING FUNDS IN THE “WRONG” YEAR

Reynolds’ communications director Brenna Smith didn’t respond to any of my questions this week about the transition expenses, but Petroski reported on August 23,

Brenna Smith, a spokeswoman for Reynolds, told The Des Moines Register on Wednesday the governor’s office is not using the $150,000 in designated transition funds because the money was appropriated by the Iowa Legislature for the current state fiscal year, which began July 1.

“The transition occurred on May 24, 2017, and all transition costs were incurred last fiscal year (FY 17). As such, the $150,000 could not be used for those expenses,” Smith said.

Similarly, Schneider told me in an August 23 e-mail,

The big picture here is that the money was appropriated for FY 2018 in anticipation of the office needing additional funds to cover the normal costs associated with a gubernatorial transition. At the time, we didn’t know whether the transition would take place in FY 2017 or FY 2018. As it turns out, the transition occurred in FY 2017.

How can that be? In early March, Branstad told reporters his U.S. Senate confirmation hearing would likely happen the first week of April, with a final confirmation vote sometime in late April or early May. (The Senate Foreign Relations Committee eventually scheduled Branstad’s hearing for May 2, and the full chamber voted to confirm him on May 22.)

Schneider answered my follow-up question on August 24.

Notwithstanding what Branstad said he expected, we didn’t know with certainty when the transition would occur, or when the expenses would need to be incurred. The governor’s office asked for the allocation, and it seemed reasonable given the precedent of allowing the Governor’s office an allocation for transition expenses.

More than six weeks ago, I requested documents, memos or e-mails from the governor’s office outlining projected expenses associated with the transition, as well as any documents showing a plan for spending the $150,000 appropriation or actual expenses incurred. The State Archive now handles requests for Branstad administration records. State Archivist Anthony Jahn told me on August 23 that he has “reviewed all the records found during our search and the State Archives legal council (State’s Attorney General’s office) has also completed their review. […] Currently the records you asked for are in the hands of Ambassador Branstad’s Agent(s) and their review is underway.” After meeting with Branstad’s representatives on August 24, Jahn said, “I’ve been advised they will have their review completed by the end of next week.”

Meanwhile, I’ve had some time to think about why the governor might ask for fiscal year 2018 funds to pay for a transition that was set to be completed well before the end of fiscal year 2017.

A MESSAGE TO THE IOWA SUPREME COURT?

What changed between March 28, when Branstad sent lawmakers new 2018 spending recommendations, and April 18, when the standings bill came out with a $150,000 line item for the gubernatorial transition?

Branstad’s top staffers learned that Attorney General Tom Miller had determined Reynolds would not have the constitutional authority to appoint a new lieutenant governor.

Bleeding Heartland told that story here. Quick recap: Solicitor General Jeffrey Thompson broke the news during a March 30 meeting with the governor’s chief of staff Michael Bousselot and legal counsel Larry Johnson. Johnson e-mailed Thompson on April 3 asking for “the ten cases you were referring to last week.” Thompson replied two days later, attaching a collection of other states’ court rulings and attorney general opinions. (See pages 1,295, 1,100, and 1,102 of this file.)

When Miller announced his conclusions on May 1, Branstad, Reynolds, and various other Republican politicians railed against a supposedly sudden reversal of the attorney general’s earlier view of the new governor’s powers.

They never admitted that the Branstad/Reynolds team had known Miller’s plans more than a month ahead of time.

Independent State Senator David Johnson had requested a formal opinion from Miller, which centered on two main questions: would Reynolds become the governor after Branstad resigned, or would she be performing the duties of that office as “acting governor”? And would the office of lieutenant governor be vacant once Reynolds assumed the governor’s powers, allowing her to fill the vacancy?

Reynolds had interviewed candidates to serve as lieutenant governor over several months, settling on three finalists for the position in April. If she and Branstad’s advisers anticipated a clash with Miller over a newly-appointed lieutenant governor, then a vote of confidence from state lawmakers could be useful in future litigation.

Legislative intent was a crucial factor in Iowa Supreme Court decisions on two lawsuits against Branstad, both filed by Democratic legislators and the leader of the largest labor union representing state employees. In 2012, the seven justices unanimously ruled that Branstad impermissibly used his line-item veto power when rejecting language attaching strings to some Iowa Workforce Development funding without vetoing the corresponding appropriation.

In 2015, the Supreme Court unanimously declined to rule on the merits of a challenge to Branstad closing the Iowa Juvenile Home in the middle of a fiscal year. The justices found “the case is moot because the legislature is no longer appropriating funds” for the facility.

In legal briefs, a $150,000 appropriation for transition expenses could be spun as a statement by lawmakers that they viewed Reynolds as the leader of a new administration, not merely the “acting governor” playing a new role for a continuing administration. The legislative branch would be on record treating the transfer of power from Branstad to Reynolds as essentially the same as Vilsack turning over the reins to Culver following the 2006 election.

In the end, Reynolds decided not to invite a lawsuit over her authority. She named Adam Gregg to “serve in an acting capacity, fulfilling all duties of the lieutenant governor’s office through the January 2019 inauguration.” Her staff acknowledged that Gregg would have no place in the line of succession, which had been a key point in Miller’s reading of the Iowa Constitution. (The Reynolds administration has since tried to rewrite history in a sense, giving Gregg the title of lieutenant governor–which he does not hold–in all official communications.)

The governor’s office has ignored all of my queries related to the Branstad team’s advance knowledge of Miller’s intentions. But I figured I had nothing to lose by putting the question to Schneider, chair of the Senate committee that drafted the standings bill. “Clearly someone wanted the legislature to be on record supporting the idea that the transition from Governor Branstad to Governor Reynolds would cost $150,000. Was that to bolster the position that Governor Reynolds would have the authority to appoint a new lieutenant governor?” Schneider answered,

No. At the time we passed the budget, most people were already operating under the assumption that Gov. Reynolds would have the authority to appoint a new LG. This includes Attorney General Miller, who had publicly opined that she would have this authority. It wasn’t until after we passed the budget that he reversed his earlier statement.

State lawmakers may have operated under that assumption in mid-April, but Miller had revised his view weeks earlier. The solicitor general gave the governor’s staff a heads up on March 30.

I’ll keep seeking information about how and when Branstad officials decided to ask Republican appropriators for $150,000 that Reynolds’ office wouldn’t be able to spend for the stated purpose.

UPDATE: A reader speculated that the fishy appropriation “may have been a placeholder for litigation related expenses” if Reynolds intended to defy Miller’s opinion by naming a lieutenant governor. That hypothesis is plausible; most of the legal bills would have been payable in fiscal year 2018.

SECOND UPDATE: In a follow-up report on August 28, Petroski failed to press Reynolds on the request for unnecessary funds. Excerpt:

Questions have arisen in recent months about spending for the governor and lieutenant governor’s office, particularly after the Republican-controlled Legislature approved a special appropriation for transition spending in the wake of Branstad’s departure in May to become U.S. ambassador to China. […]

Reynolds told The Des Moines Register on Monday that a transfer of up to $40,000 in previously appropriated state funds to handle her transition from lieutenant governor to governor was needed to accommodate an “overlap” on salaries for existing staff that was still working and for newly hired staff. In addition, departing staff members received payments for accrued vacation, which is customary in state government, she noted.

Reynolds is not spending any of the special appropriation of $150,000 because the money was designated for the current state fiscal year and her transition occurred in the previous fiscal year.

“The bottom line is that if you check, our overall budget is still less than it was in 2011 when we took office,” Reynolds said. Under Branstad and Reynolds, the governor and lieutenant governor’s office have done a “pretty darn good job” of operating with limited dollars, she added.

The total annual budget for the governor’s office isn’t the “bottom line” here at all. Nevertheless, the Register rewarded the governor’s attempt to change the subject by making her non-sequitur the frame for Petroski’s story, headlined “Reynolds says her office budget will be less than Branstad and Culver.”

Reporters with access should be asking tough questions:

Why didn’t Branstad and Reynolds include transition funding in draft budgets submitted to the state legislature in January and March?

What prompted the last-minute ask for $150,000 in fiscal year 2018 funds, when it was clear by April that the transition would happen in fiscal year 2017?

Was the $150,000 appropriation related to a planned legal fight over Reynolds’ authority to name a new lieutenant governor?

Speaking of timid Iowa political news coverage, more than two months have passed since Bleeding Heartland published documents disproving the official Republican storyline about the attorney general’s opinion. To my knowledge, no mainstream media organizations ever corrected the record.