President Donald Trump changed the subject last night. Instead of another day of news on the fallout from his horrific response to a white supremacist rally, the commander in chief announced a new strategy for the U.S. in Afghanistan in a prime-time televised address. It wasn’t a typical Trump speech: he read carefully from a teleprompter.

Foreign policy isn’t my strong suit, so I’ve spent much of today reading analysis by those who have closely followed our military and diplomatic strategy during our country’s longest war. The consensus: Trump’s strategy for Afghanistan is neither new nor likely to produce the victory the president promised.

To my knowledge, the only Iowan in Congress to release a public statement on last night’s speech was Senator Joni Ernst. I enclose her generally favorable comments near the end of this post, along with a critical statement from Thomas Heckroth, one of the Democrats running in Iowa’s first district. James Hohmann compiled some other Congressional reaction for the Washington Post.

For those who missed the speech, here’s the full text of Trump’s remarks, and here are some of the most significant lines.

The most detailed reporting on Trump’s decision-making process came from the Washington Post’s Philip Rucker and Robert Costa. Steve Bannon’s departure was a big part of the story. But you have to hand it to H.R. McMaster for finding the perfect argument to sway his boss:

Years before running for president, Trump had a clear message on Afghanistan: It was time to get out. In 2012, he said the war was “wasting our money.” In 2012, he called it “a total disaster.” In 2013, he said, “We should leave Afghanistan immediately.” Trump continued his criticism of the war during the year and a half he campaigned for the White House.

But since becoming president, he has faced a different set of opinions. Defense Secretary Mattis and national security adviser H.R. McMaster, both generals with extensive battlefield experience in Afghanistan, warned Trump about the consequences of withdrawal and cautioned that any move in Afghanistan would have ripple effects throughout the region.

One of the ways McMaster tried to persuade Trump to recommit to the effort was by convincing him that Afghanistan was not a hopeless place. He presented Trump with a black-and-white snapshot from 1972 of Afghan women in miniskirts walking through Kabul, to show him that Western norms had existed there before and could return.

For foreign policy experts, the president’s tough talk about Pakistan was the most noteworthy shift: “We have been paying Pakistan billions and billions of dollars at the same time they are housing the very terrorists that we are fighting. But that will have to change, and that will change immediately. No partnership can survive a country’s harboring of militants and terrorists who target U.S. servicemembers and officials. It is time for Pakistan to demonstrate its commitment to civilization, order, and to peace.”

According to Politico’s Susan Glasser, “Whether and how harshly to call out Pakistan […] was among the most contentious elements of a debate that raged all the way up until last Friday’s national security team meeting at Camp David.” Adam Weinstein noted that Trump doesn’t seem to realize Saudi Arabia (where he had a warm visit with rulers earlier this year) indirectly provides a lot of the Taliban’s funding. Meanwhile, Steven Mazie pointed out, “Trump says Afghanistan and Pakistan pose the worst terrorist threat to America. Interesting his travel ban applies to neither country.”

Glasser illuminated the larger problem in her commentary, worth reading in full. Excerpts:

President Trump proved one thing beyond the shadow of a doubt in his Afghanistan strategy speech Monday night: After nearly 16 years of fighting America’s longest war, there are no new ideas.

He called his plan “dramatically different.”

It wasn’t. The only thing that seemed a striking change from his two presidential predecessors’ approach to the war launched after the attacks of September 11, 2001, was Trump’s escalatory rhetoric. He repeatedly vowed to “win” a conflict that his Defense Secretary James Mattis told Congress recently “we are not winning” and sharply criticized Afghanistan’s neighbor Pakistan, a troublesome ally Trump excoriated for offering “safe haven” to terrorists. […]

But beyond the scathing language and an open-ended pledge to “fight to win,” Trump offered few details about a plan that administration sources have said involves the sending of a few thousand more troops to Afghanistan. The Pentagon deems such a move necessary to avoid the collapse of the U.S.-backed government in Kabul but it would hardly be a force capable of dramatically changing facts on the ground a few years after a surge to some 100,000 American troops at the beginning of Barack Obama’s presidency failed to do so. […]

Not long ago I interviewed Laurel Miller, who served as America’s top diplomat for Afghanistan and Pakistan until the end of June, when she left the State Department and the Trump administration shut down her office. Here is what she had to say on the subject of winning, a sentiment echoed by numerous other current and former U.S. officials with whom I’ve spoken about this in recent weeks:

“I don’t think there is any serious analyst of the situation in Afghanistan who believes that the war is winnable. It’s possible to prevent the defeat of the Afghan government and prevent military victory by the Taliban, but this is not a war that’s going to be won, certainly not in any time horizon that’s relevant to political decision-making in Washington.”

Spencer Ackerman reached a similar conclusion in his piece for the Daily Beast on “Trump’s Afghanistan War Plan: Fight Forever and Call It ‘Victory.’”

After insisting beyond the limits of credulity that he has “studied Afghanistan in great detail and from every conceivable angle,” Trump made an expansive pledge of what the purpose of U.S. strategy in Afghanistan will be. The “clear definition” of victory, he said, will be “attacking our enemies, obliterating ISIS, crushing al Qaeda, preventing the Taliban from taking over Afghanistan, and stopping mass terror attacks against America before they emerge.”

It does not take Carl von Clausewitz to immediately see that this conception of victory is not an end state at all but rather a process. To give it perhaps more credit than it deserves, it would be called a strategy of attrition, something no one who has studied either Afghanistan or counterterrorism in great detail and from every conceivable angle thinks is achievable. An Obama-era surge that totaled 100,000 American troops, by any measure an unsustainable effort, did little more than cause the Taliban tactical setbacks.

Put more descriptively, Trump is defining victory in terms of things the military must keep doing—attacking, obliterating, crushing, preventing, stopping. That gives the lie to Trump’s hand-wave that “our commitment is not unlimited, and our support is not a blank check.” The only way for the Trumpist conception of victory to mean anything is for American troops to patrol Afghanistan indefinitely, until the ever elusive and indefinable point when their Afghan protégés can outlast the Taliban.

Trump criticized President Barack Obama last night: “As we know, in 2011, America hastily and mistakenly withdrew from Iraq. […] When I became President, I was given a bad and very complex hand. […] We cannot repeat in Afghanistan the mistake our leaders made in Iraq.” But as Jared Keller noted in his story for Task and Purpose,

For nearly six years before he was president of the United States of America, Donald Trump desperately wanted the U.S. military to withdraw from Afghanistan. […]

And just like Obama, Trump is now tasked with delivering the same frustrating message to the American public: The forever war will last at least a bit longer. […]

It’s unclear whether those additional troops will do the trick. Afghanistan remains scarred by the steady resurgence of Taliban forces and rise of ISIS-K in recent years, prompting an increase of U.S. special operations forces missions against terrorist targets and bombing sorties that culminated with the use of the GBU-43 Massive Ordnance Air Blast (MOAB) against ISIS targets in the Nangarhar province.

And an increase in operational temp comes with casualties. On Aug. 17, a U.S. service member was killed during a joint operation in eastern Afghanistan, the seventh killed in battle against ISIS-K and tenth overall in the country since the beginning of 2017.

Writing for The Atlantic, James Fallows saw Trump’s address as “depressingly normal”: “It’s like any of the speeches that other politicians could have given about Afghanistan, which the pre-presidential Trump ridiculed for having no end point or concept of victory.”

Adam Weinstein’s take seems apt. Trump is promising us “a pony, the best pony.”

Amy Davidson Sorkin saw the president determined not to learn from history.

The entire speech was a tirade against boundaries and borders and the systems of accountability that are meant to keep America from getting involved in unending wars conducted in manners that later make us ashamed. Its most extraordinary line may have come as he described how American strategy “in Afghanistan and South Asia” will “dramatically change” in the coming days: “We will not talk about numbers of troops or our plans for further military activities.” There are, in any war, secret deployments and operations, but Trump is enshrining the idea of secret wars, with secretly mustered armies. In briefings to reporters, various Administration officials have mentioned deploying four thousand additional troops, with the intimation that there were generals who wanted Trump to send more. He has made it easy for that number to be elastic, and to stretch without public restraint.

His plan for the war, on a tactical level, is to hand it over to “wartime commanders”—a striking phrase. “Micromanagement from Washington, D.C., does not win battles,” Trump said. But differentiating between the micro and the macro has never been one of Trump’s strengths. And a lack of leadership, including moral leadership, can lose not only battles but wars. Trump said that he had already “lifted restrictions” on what troops could do in the field, and would lift more, so that they had ever greater power to act “in real time, with real authority.” It is hard to know exactly what this will mean, given that American forces already have a great deal of leeway. A certain number of restraints involve concern for the lives of civilians. Even with those now in place, there have been incidents like the American air strike, in 2015, that hit a Doctors Without Borders hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan, killing forty-two people and cutting off access to medical care for many more. If Trump cannot see how these are not only tragedies but moments that turn populations against the United States, we may see a very long war get longer and more brutal.

Longtime foreign policy reporter Laura Rozen found “small consolation” in the likelihood that Trump “is not any more convinced of this strategy than anyone else.”

I don’t see how this ends well for the country. It could have been worse, I suppose: Trump could have approved a plan to outsource the military campaign in Afghanistan to Erik Prince’s company, Blackwater.

Statement from Senator Joni Ernst, released August 21:

“As a veteran and member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, I do not take lightly the decision to commit America’s young men and women to conflict. Unfortunately, the reality is this: arbitrary timelines, troop levels, and an overall lack of strategy from the previous Administration has created an environment in Afghanistan where 20 of the world’s international terror networks reside, the Taliban is resurging, and the region is vulnerable to the malign influence of Iran and Russia. As Secretary James Mattis recently described, ‘we are not winning in Afghanistan.’

“Maintaining the status quo is unacceptable to our national security and unacceptable to our troops and their families.

“Tonight the President outlined his vision for a new strategy in Afghanistan – one which prioritizes the need for increased cooperation with regional partners such as Pakistan and India.

“Now is not the time to abandon our fight against terrorism in Afghanistan, its people or our international partners. Instead, we must once again lead from a position of strength. Therefore, moving forward, I am committed to both guaranteeing our servicemembers are well-equipped for combat, while also holding the Department of Defense and the Administration accountable for ensuring the effectiveness of this strategy.”

Statement from Democratic Congressional candidate Thomas Heckroth, released August 22:

“In his address to the nation last night, President Trump failed to outline a clear plan for victory in Afghanistan. If the President intends to expand the longest war in American history in Afghanistan, he needs to work with Congress to define success and set us on a clear path forward that will bring our men and women in uniform home. Too many Iowa families have already sacrificed for this war – it would be irresponsible to commit more troops without a clear exit strategy or the diplomatic support to make it a reality. As a member of Congress, I would oppose open-ended commitments of our servicemen and women and I will stand up for Iowa soldiers and their families to ensure they have the resources and support they need when they return home.”

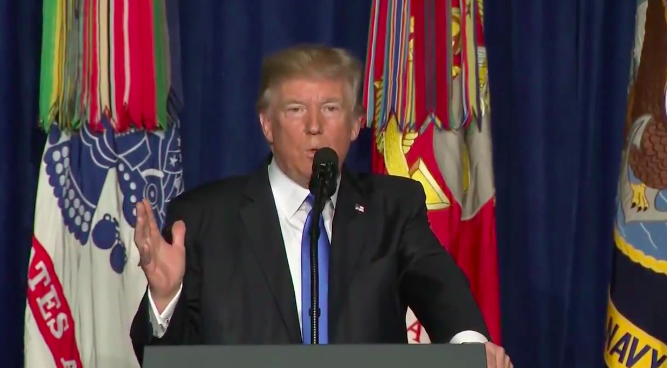

Top image: Screen shot from Donald Trump’s August 21 prime-time address on Afghanistan.