Randy Richardson explains how Iowa’s new collective bargaining law is affecting contract negotiations for teachers. -promoted by desmoinesdem

A lot has been written about the changes Republican lawmakers pushed through on collective bargaining for public employees. The original law, adopted during the term of a Republican governor and approved by a bipartisan vote, has been in existence for over forty years. I became a chief negotiator for our local education association during my second year as a teacher (1977) and remained active in bargaining until my retirement in 2016.

As a former teacher I can appreciate the trauma these changes have brought about for educators. Unfortunately the general public, who has likely not participated in the bargaining process, may find some of these changes hard to understand.

Since its inception, public sector bargaining in Iowa has operated under a relatively stable set of rules. Teachers typically elected a team to represent their interests at the bargaining table. This team was led by the chief negotiator. This team began deliberations with a similar team made up of school board members and district administrators. However, some school boards/administrators decided they didn’t like to participate in the process so they made the decision to hire outside law firms to represent their interests. Approximately six law firms around the state handle the bulk of those districts. This usually cost the district several thousand dollars each year with costs increasing when the parties couldn’t reach an agreement.

The process usually began in January and ended in May. If it appeared that the two sides couldn’t come to a voluntary agreement they would ask the Iowa Public Employer Relations Board (PERB) to appoint a mediator. The mediator would then try to facilitate an agreement between the parties. However, the mediator would not have the power to enforce an agreement. Many times the sides would reach an agreement during or shortly after mediation. In the rare event that mediation didn’t result in an agreement, the parties would once again turn to PERB, who would appoint an arbitrator. Arbitration was a more formal process where the two sides presented evidence supporting their positions. The arbitrator would then consider the arguments and issue a decision on each separate issue.

The rules also stipulated what issues could be bargained. The law said that some issues were mandatory topics that both sides had to discuss and that could go to an arbitrator. There were permissive items that the sides could discuss if both parties agreed to do so. There were also a small number of illegal items that the two sides were forbidden to discuss, although, in reality, some groups ignored the law and placed those items in collective bargaining agreements. Once the new law went into effect the number of mandatory items was reduced to one item: base salary. All other items were now permissive or illegal.

Just about half of the local education associations (unions) were able to reach an agreement on a new contract or extend an existing one prior to the change in the law. Most of the rest of the locals were in the process of doing so when the law changed. Once the new law went into effect those locals were forced to start the process over. This was a new experience for everyone, but school districts quickly found that the playing field now slanted heavily in their direction.

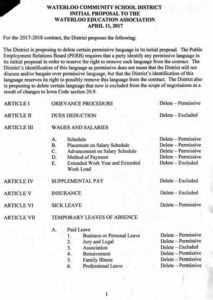

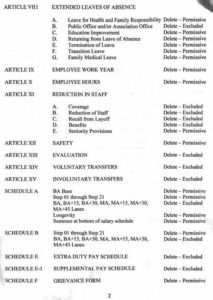

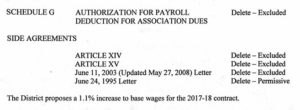

A few districts decided that the relationship with their teachers was important and made a decision to keep language that was now permissive or illegal in the collective bargaining agreement. This language had been agreed to over many years by both sides. However, several districts saw an opportunity get rid of this language and made proposals to the union that removed every permissive and illegal item from the collective bargaining agreement. Waterloo and Fort Madison are two of those districts. Photos of the initial contract offer for Waterloo (click to enlarge):

I should point out that these types of proposals aren’t completely new. Some districts that were represented by two of the law firms have proposed eliminating permissive language from contracts in previous years. However, under the old law, local association bargaining teams had enough leverage to force the employer to keep the language in place. Under the new law these proposals are likely to become reality. Although this is legal, it is incredibly short-sighted of school districts.

Proposals that gut existing contract language will destroy whatever goodwill was established between the school district and the local association over the years. It will take many years to repair this damage.

While this is a traumatic experience for teachers, it does give local associations an incredible organizing opportunity. Many Iowans are upset about the actions of the legislature, but don’t fully understand the impact it will have on working conditions and the morale of teachers statewide. This gives teachers an opportunity to educate the public on what these changes will mean.

It also gives them time to prepare for school board elections that will take place in September. School board members who voted to gut these agreements may very well face opponents who were recruited and supported by local teacher groups. Local association leaders should consider holding forums for school board candidates so that they can publicly ask candidates where they stand on these changes.

This is a difficult time for many public employees around the state, but this isn’t the time to give up. Instead it’s the time to unite and begin building toward the future. We don’t want our state to become another Wisconsin where teachers were in disarray following the loss of bargaining. This allowed Republicans to consolidate their power in the next election. In Iowa the fight back begins with school board elections this September and continues through November 2018.

Randy Richardson is a former teacher and retired associate executive director of the Iowa State Education Association.