Governor Terry Branstad has rarely found himself at odds with any powerful farm lobby group. In 1995 he signed a law banning agricultural zoning, which fueled explosive growth of confined animal feeding operations across Iowa. Since returning to the governor’s office in 2011, he has named several agribusiness representatives to the the Environmental Protection Commission. He signed the probably unconstitutional “ag gag” bill targeting whistleblowers who might report alleged animal abuse. He moved to protect farmers from state inspections for electrical work. He joined a poorly-conceived and ultimately unsuccessful lawsuit seeking to block a California law on egg production standards. He has consistently rejected calls to regulate farm runoff that contributes to water pollution, instead supporting an all-voluntary nutrient reduction strategy heavily influenced by the Iowa Farm Bureau.

Despite all of the above, the governor’s two-year budget blueprint contains an obscure proposal that will draw intense opposition from Big Ag. By this time next year, the fallout could cause political problems for Branstad’s soon-to-be-successor, Lieutenant Governor Kim Reynolds–especially if Cedar Rapids Mayor Ron Corbett challenges her for the 2018 GOP nomination.

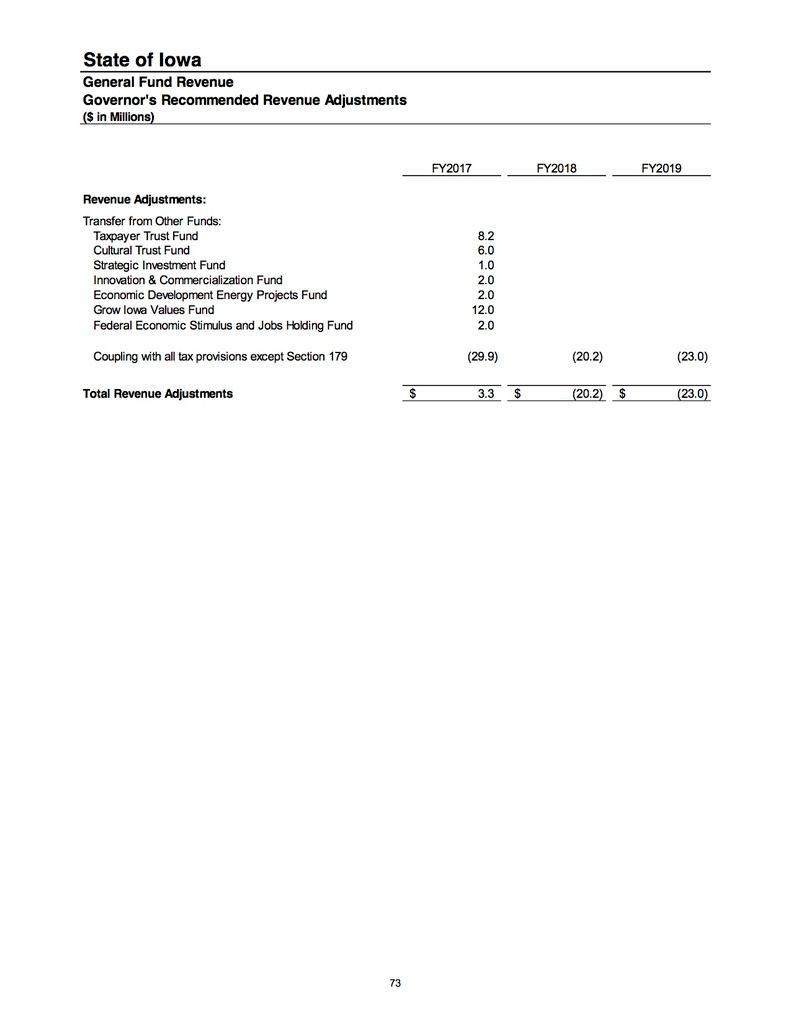

Branstad proposed more than $110 million in spending cuts to balance the budget for the current fiscal year, which ends June 30. He also suggested some revenue adjustments (page 73):

“Coupling with all tax provisions except Section 179” will set off alarm bells for farm groups.

Every year, Iowa lawmakers approve legislation “coupling” state tax code with federal provisions. Usually the bill passes early in the legislative session, in time for tax preparers to use before submitting tax returns for clients. Coupling measures have rarely been controversial; the 2015 version cleared both chambers unanimously. The fiscal note for that bill explained,

Senate File 126 conforms Iowa’s revenue laws to incorporate federal changes enacted from January 1, 2014, through January 1, 2015. The Bill is effective on enactment and applies retroactively to tax year 2014. […]

Of the extended provisions, the most significant from a fiscal impact perspective is the extension of favorable depreciation expensing known as “Section 179 expensing.” This provision allows business taxpayers (including corporate taxpayers and business entities taxed through the individual income tax) to write off additional depreciation in the year a qualified depreciable asset is placed in service. Since the provision accelerates the claiming of depreciation, the provision reduces taxes owed in the first year, but increases taxes owed in later years.

Analysts for the Legislative Services Agency estimated that the 2015 coupling bill would reduce state revenue by $98.98 million during the first year, of which $83.5 million came from the Section 179 expensing.

Congress made Section 179 expensing a permanent part of federal tax code in a December 2015 omnibus bill.

At the beginning of the 2016 legislative session, Branstad’s proposed budget assumed lawmakers would couple Iowa tax code with federal changes for 2016, but not retroactive to 2015. The governor and his chief budget architect David Roederer concluded that coupling would have been too expensive, mostly because of Section 179, depriving the state of funds needed for education and other programs.

Nevertheless, state lawmakers approved a coupling bill retroactive to 2015 last year. Its fiscal note estimated the coupling provisions would reduce revenue by $97.6 million during the first year, of which $77.8 million came from Section 179 expensing.

Branstad signed last year’s bill, but you can see why his new blueprint left out Section 179. Iowa’s budget is already some $110 million out of balance for the current fiscal year. Coupling legislation retroactive to 2016 that includes Section 179 would put the state in the hole by tens of millions more dollars.

Looking forward, the governor proposes coupling with other federal tax code provisions for fiscal years 2018 and 2019, costing $20.2 million and $23.0 million, respectively. Section 179 expensing would reduce revenues by much more, in the range of $80 million each year.

Branstad’s spokesperson Ben Hammes is in one of his spells of ignoring all of my queries for weeks at a time, so I was unable to confirm yesterday or today whether Lieutenant Governor Reynolds shares Branstad’s stance on this tax policy. Assuming the U.S. Senate confirms Branstad as ambassador to China, Reynolds will present a draft budget for fiscal years 2019 and 2020 at the beginning of next year’s legislative session. Later, she will decide whether to sign any coupling bill that includes Section 179 expensing.

Reynolds will be forced to confront this issue at some point, because Section 179 is a high priority for heavy-hitters such as the American Farm Bureau Federation and its state affiliates. Thousands of Iowans who benefit from the provision are farmers. The lobbyist declarations for the first coupling bill introduced in 2016 showed every major agricultural group in favor: Iowa Farm Bureau Federation, Iowa Corn Growers Association, Iowa Soybean Association, Iowa Pork Producers Association, and Iowa Cattlemen’s Association. Don’t bet against that coalition when they come knocking on state lawmakers’ doors. New Iowa Senate President Bill Dix is himself a farmer with a history of supporting just about every business tax break you could imagine.

By January 2018, Reynolds will be campaigning for governor as well as performing the duties of that office. Although Iowa Secretary of Agriculture Bill Northey has ruled against running against her, she may have competition in the GOP primary from Cedar Rapids Mayor Ron Corbett.

While laying the groundwork for a gubernatorial campaign in recent years, Corbett has built a strong alliance with the Iowa Farm Bureau as front man for its so-called “Iowa Partnership for Clean Water.” The mayor and his conservative think tank have also called for raising the state sales tax to pay for water quality programs. Many environmental organizations support that policy, as do some farm groups, since it would make consumers pay to clean up water pollution largely emanating from farm operations.

Corbett may decide against running for governor, now that Reynolds will have tremendous establishment support as the incumbent in a GOP primary. But the Section 179 controversy gives him an opening to solicit backing from PACs and individual donors associated with Big Ag groups, if Reynolds leaves the expensive provision out of her budget, or goes one step further than Branstad and vetoes a coupling bill that includes Section 179.

Stay tuned.

UPDATE: Joe Kristan commented on this post at his blog for tax professionals.

This is about the politics behind the fight to allow Iowa taxpayers to take the same $500,000 Section 179 deduction for equipment that would otherwise be capitalized and depreciated. Governor Branstad wants to cap it $25,000.

Section 179 is not really a “Big Ag” deduction. It phases out for businesses that place over $2 million of property in service in a year. That makes it unavailable for the Cargills of the world, and for large hog operations. That aside, the post nicely summarizes the Iowa Sec. 179 political battle.

I was using the term “Big Ag” to describe lobbying groups like the Corn Growers, Farm Bureau, Pork Producers, and so on. But Kristan’s point is well taken: major corporations in the agricultural sector cannot use the Section 179 deduction.