Iowa Secretary of State Paul Pate is a defendant in Kelli Jo Griffin’s lawsuit claiming Iowa violates her constitutional rights by disenfranchising all felons. The Iowa Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case on March 30. Justices are expected to decide by the end of June whether to uphold the current system or declare that Iowa’s constitutional provision on “infamous crimes” should not apply to all felonies.

Defendants typically refrain from commenting on pending litigation, but during the past three weeks, Pate has carried out an extraordinary public effort to discredit the plaintiffs in the voting rights case. In his official capacity, he has addressed a large radio audience and authored an op-ed column run by many Iowa newspapers.

Pate amped up his attack on “the other side” in speeches at three of the four Iowa GOP district conventions on April 9. After misrepresenting the goals of Griffin’s allies and distorting how a ruling for the plaintiff could alter Iowa’s electorate, the secretary of state asked hundreds of Republican activists for their help in fighting against those consequences.

At a minimum, the secretary of state has used this lawsuit to boost his own standing. Even worse, his words could be aimed at intimidating the “unelected judges” who have yet to rule on the case. Regardless of Pate’s motives, his efforts to politicize a pending Supreme Court decision are disturbing.

PATE SEES VOTING AS A “PRIVILEGE,” NOT A FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT

Pate submitted his commentary to scores of Iowa newspapers and posted it at a conservative blog two days after the Iowa Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Griffin v. Pate. Excerpt:

My role as secretary of state includes presiding as Iowa’s commissioner of elections. Unfortunately, there is a lot of misinformation out there regarding our state’s voting laws. I would like to clarify and clean up some misconceptions.

First, Iowa does not permanently disqualify felons from voting. Anyone who tells you otherwise is misinformed or is misleading you. All Iowans convicted of a felony have the opportunity to have their voting privileges restored, unless they are serving a life sentence behind bars.

I use the word “privileges” because voting for our representative form of government is a privilege. Hundreds of thousands of our brave men and women fought and died to ensure all U.S. citizens had that sacred privilege. Our state’s founding fathers used the term “privilege” in regards to voting when they drafted the Iowa Constitution 160 years ago.

Indeed, Iowa’s 1857 Constitution stated in Article II Section 5, “No idiot, or insane person, or person convicted of any infamous crime, shall be entitled to the privilege of an elector.” But the title of Article II is “Right of Suffrage.” Federal and state courts have repeatedly held that voting is a fundamental right, which may be restricted only in the service of a compelling government interest.

Here’s the first sentence of U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts’ opinion for the majority in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission (a campaign finance case): “There is no right more basic in our democracy than the right to participate in electing our political leaders.”

From the Iowa Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Devine v. Wonderlich:

The right to vote is a fundamental political right. It is essential to representative government. Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1, 17-18, 84 S. Ct. 526, 535, 11 L. Ed. 2d 481, 492 (1964) (“No right is more precious in a free country than that of having a voice in the election of those who make the laws under which, as good citizens, we must live.”). Any alleged infringement of the right to vote must be carefully and meticulously scrutinized.

The Iowa Secretary of State’s own website repeatedly uses the terms “voting rights” or the “right to vote.” One page mentions “our sacred right to vote.” I was unable to find any reference to voting “privileges” on that site.

PATE DOWNPLAYS THE OBSTACLES TO REGAINING THE RIGHT TO VOTE

In his newspaper commentary, Pate asserted,

Unfortunately, some Iowans have forfeited that privilege, but it is not an arduous process to have it restored. Once felons complete their sentences and pay their debt to society, or are on track to pay restitution, they can request that the governor’s office restore their voting privileges.

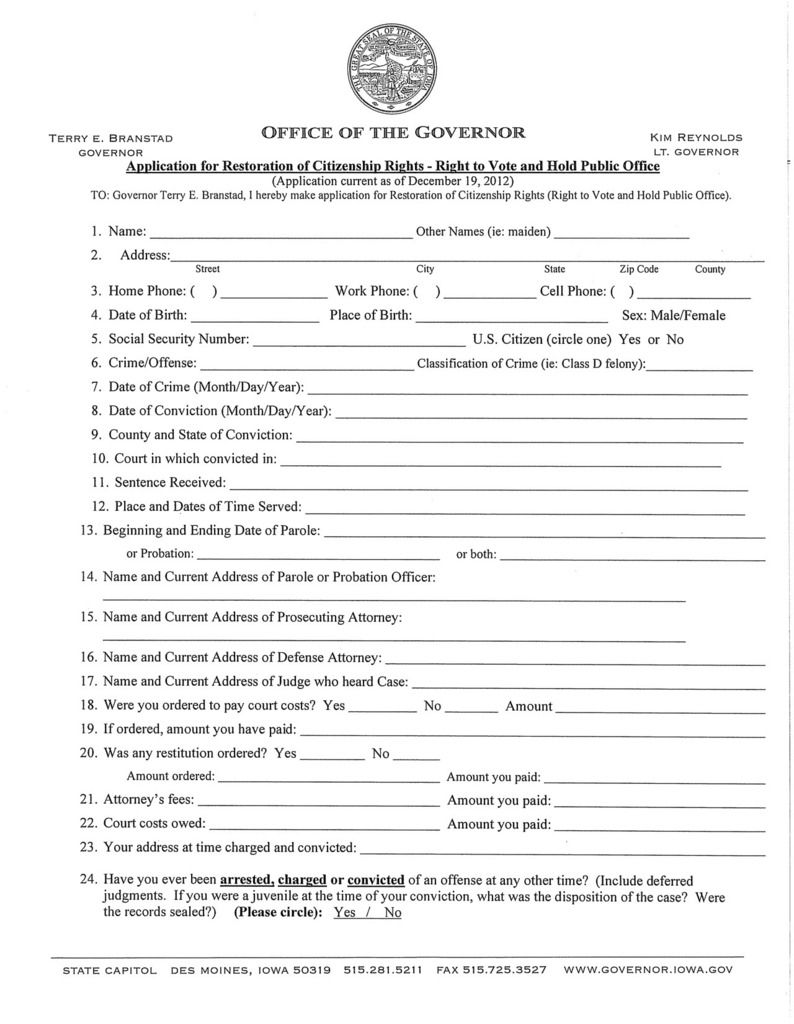

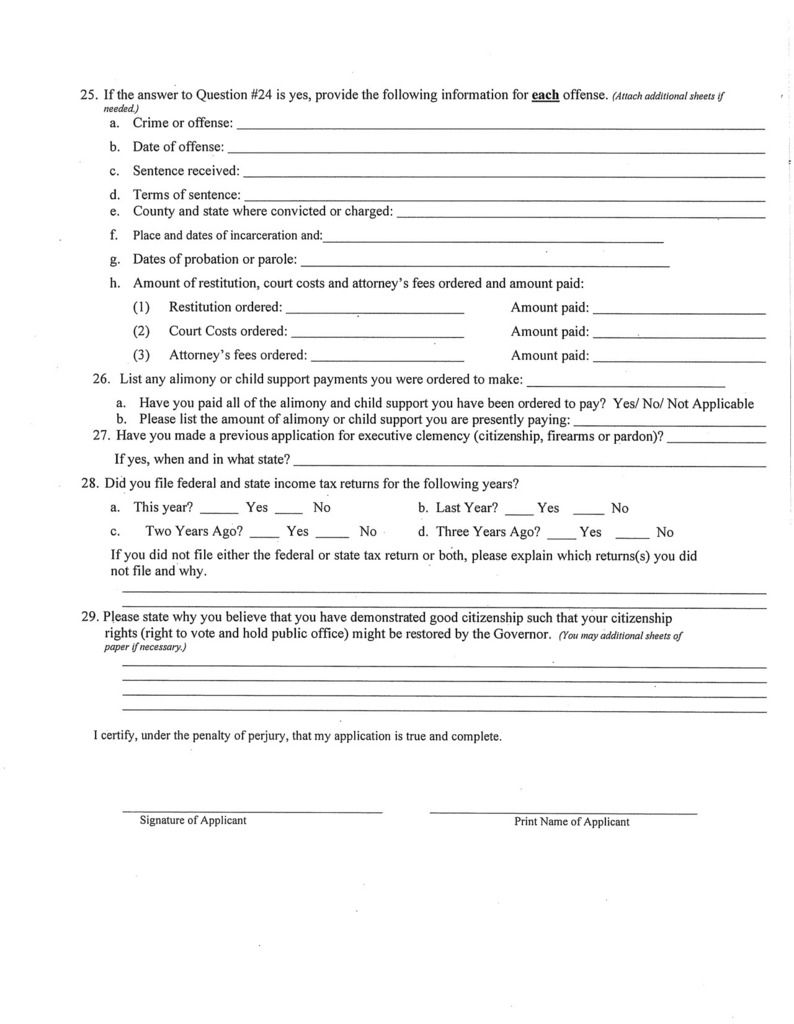

Despite what you might have heard, the process is not difficult. Felons can fill out a simple 29-question form and send it to the governor’s office. Within a couple of months, chances are very good that their privileges will be restored.

Pate echoed that talking point about a “simple little questionnaire” during his April 4 interview on a popular conservative talk radio program.

Governor Terry Branstad created a new process for regaining voting rights by executive order on the day he took office in January 2011. Nearly two years later, the governor “streamlined” the process by shortening the application from 31 to 29 questions, removing the requirement that applicants submit a credit history check, and relaxing the burden on felons to prove they have paid all fines, restitution and court costs. Under the current policy, applicants may have voting rights restored if they have been “making consistent payments in good faith” toward settling those debts.

On principle, I oppose making the right to vote contingent on a person’s ability to pay fines or fees of any kind. In effect, Branstad has established a poll tax for a large group of Iowans. Just like old-fashioned (and now outlawed) poll taxes, this financial requirement for voting disproportionately burdens racial minorities.

Pate depicted a simple process for regaining the right to vote. The NAACP’s amicus brief in the Griffin case presented the reality:

Iowa has one of the most restrictive felon disfranchisement laws in the country: anyone convicted of a felony in Iowa is permanently barred from voting, unless their voting rights are restored by the Governor. The only other state with a similarly strict regime is Florida. […]

Iowa has one of the most restrictive laws governing the restoration of voting rights.60 Pursuant to the process established by the Governor, Iowans seeking the restoration of their voting rights must complete an application and submit proof of payment of court costs, fines, restitution, and their current Iowa criminal history record. The application contains 29 questions and requires the applicant to detail any alimony or child support payments s/he has been ordered to make and whether or not the applicant has filed federal and state income tax returns for the previous four years.61 In order to obtain information regarding the applicant’s criminal history and court costs, restitution, and fines, which must be submitted with the application, applicants must request information from several government agencies.

This process is invasive and cumbersome, and requires time and money to complete – often scarce resources for individuals with prior felony convictions.62

The discretionary nature of the process also creates an unfair barrier for those seeking restoration. For example, applicants must respond to the following prompt: “Please state why you believe that you have demonstrated good citizenship such that your citizenship rights (right to vote and hold public office) might be restored by the Governor.”63 There are no standards or safeguards in place to guarantee that reviewers will not reject an application based on an “unsatisfactory” answer.

Pate’s op-ed column further argued,

It is very disappointing that the same special interest groups that claim to want to help Iowans vote have chosen not to help felons utilize this process.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Iowa, which is representing Griffin in her lawsuit, does provide information on how to regain voting rights. But Griffin testified during her 2014 perjury trial that she didn’t know about Branstad’s executive order. She (and presumably thousands of similarly situated Iowans) had been told she would be eligible to vote again after completing her probation. A non-profit organization with a small staff in Iowa, like the ACLU or the NAACP, cannot be expected to seek out tens of thousands of Iowans and guide them through the process. One unsuccessful applicant couldn’t get his voting rights back even after spending $500 on an attorney to help with the questionnaire. The “streamlined” application asks for lots of information that could be difficult to obtain.

Only 40 Iowans (out of at least 25,000 who had completed felony sentences) regained their voting rights during the first three years Branstad’s executive order was in effect. I sought current statistics from the governor’s office. According to Branstad’s deputy legal counsel Colin Smith, between January 14, 2011 and December 31, 2015,

a total number of 96 individuals, who did not already have their voting rights and who were otherwise eligible to receive them, submitted completed voting rights applications to the Office of the Governor. Of those 96 relevant applications, 89 resulted in a restoration of voting rights. The remaining 7 applicants who did not receive a restoration of their voting rights during this relevant time period were individuals who submitted their voting rights applications so late in calendar year 2015 that their applications could not be processed until early calendar year 2016. All 7 of those individuals in fact did have their voting rights restored in early calendar year 2016. As a result, 100% of the individuals who submitted completed voting rights applications during the relevant time period, who did not otherwise have their voting rights, and who were otherwise eligible to have their voting rights restored, had their voting rights reinstated. […]

The test for our office is simple: if an individual has submitted a complete application, and they have fully discharged their sentence and have either already paid, or are on a bona fide payment plan with respect to any outstanding financial obligations tied to their offense, they are eligible to — and do — receive a restoration of their voting rights.

The only instances where individuals who submit applications to our office do not receive a restoration of their voting rights are when: (1) The individual in question already has their voting rights or never lost their voting rights in the first instance, either by receiving a mere deferred judgment, committing only a misdemeanor, or by being previously covered under Executive Order 42; (2) The individual in question is required to have their voting rights restored by a state other than Iowa; or (3) The individual in question has not yet fully discharged the offense that precipitated the loss of their voting rights in the first instance. In each of these three types of cases, our office either informs these individuals that they are legally ineligible to receive a restoration of their voting rights from the State of Iowa at the time of their application, or, we inform these individuals that they may already have their voting rights or may have had their voting rights restored by the laws of another state.

Smith went on to say that the governor’s staff tries to “work collaboratively” with applicants who submit incomplete applications “to see if that information can be reasonably obtained.”

While our office does not keep statistics regarding the most common pieces of missing information from submitted voting rights applications, it is not an overstatement to say that members of the Governor’s staff spend meaningful amounts of time every day assisting constituents and applicants in completing their voting rights applications.

It is not the policy of the Governor’s Office to reject or deny any voting rights restoration applications if certain necessary, pertinent information is missing when an application is initially submitted. Instead, it is the longstanding policy and practice of the Governor’s Office to provide any and all assistance necessary and reasonable to constituents and applicants to help them supplement their applications where certain necessary, pertinent information is missing. For example, our office often assists with answering simple questions about the application process and the standard application form, and also assists with obtaining criminal history background checks for individuals unfamiliar with how to request them, and assists with obtaining proof of payment or payment plan information for individuals unfamiliar with how to obtain that information. Additionally, our office staff spends considerable time every day taking and returning phone calls from and to individuals who are curious about having their voting rights restored. For each and every single individual who does not have their voting rights restored and who is eligible to receive them, our office makes every reasonable effort to make sure that those individuals are given the best customer service possible to help them achieve their goal.

Smith added that the governor’s office tries to process applications quickly and “works very closely with the Secretary of State’s Office” to update the state’s databases promptly. “We do this so that those individuals who have been granted a restoration of their voting rights do not experience difficulties on Election Day when they go to register to vote or cast their ballot.”

Perhaps the governor’s staffers feel deserving of accolades because they spend “meaningful amounts of time every day assisting constituents and applicants in completing their voting rights applications.”

Their collective efforts over more than five years have resulted in 96 Iowans regaining their voting rights, out of an estimated 57,000 people who completed prison terms or probation for felonies since January 2011. All those hours of labor have helped restore a fundamental right to fewer than 20 people a year, on average. Although Branstad got a lot of good press after announcing the “streamlined” voting rights restoration process in December 2012, the low number of applicants since then indicates that the 29-question form is not significantly less burdensome than the original 31-question version.

Instead of congratulating themselves because “100% of the individuals who submitted completed voting rights applications during the relevant time period, who did not otherwise have their voting rights, and who were otherwise eligible” got their voting rights back, Smith and his boss should acknowledge the barriers that keep more than 99.8 percent of disenfranchised Iowans from ever casting another ballot.

Putting your life back together after a felony conviction involves many personal challenges, including limited employment prospects. You’re not likely to have extra money to put toward requesting official documents or paying down debts for attorney’s fees or court costs. Even if you knew where to go to find all the required information, you probably wouldn’t have endless hours to spend confirming details about your case or the current address of various people who were involved with your conviction.

Branstad paid lip service to criminal justice reform during his annual speech to state lawmakers in January. He could show commitment to his stated desire to “address the significant racial disparities” and promote “a lower rate of reoffending” by rescinding his voting rights executive order. That Iowa’s current policy disproportionately affects racial minorities is not debatable. Anthropologist Susan Greenbaum has cited research indicating “that re-enfranchising ex-felons cuts the rate of recidivism by at least 10 percent.”

Under the Branstad policy, less than two-tenths of 1 percent of felons have managed to apply to have their voting rights restored. Yet Pate pushes a narrative about “very good” chances for felons to regain their rights after filling out “a simple 29-question form.” The secretary of state told WHO Radio listeners on April 4 (around the 5:20 mark),

If you commit a heinous crime like that, you ought to pay a price. At least until you show that you’ve turned your life around. […] We don’t even expect them to have fully paid off their fines or their full restitution. But you have to just demonstrate that you’re, you’re doing that, that you’re trying to be a better person. But the bottom line here is everybody has an opportunity to vote if they follow the process. And the process is not a challenging one. Again, just be a good citizen. […] We’re reacting to I think a lot of special interest groups from the east coast are coming here and trying to tell us our constitution is wrong? After 160 years?

Does Pate believe only 96 out of the 57,000 Iowans affected by Branstad’s executive order have turned their lives around and are trying to better themselves? Does he think being a good citizen depends on having enough disposable income to make regular payments toward fines, court costs, or attorney’s fees? Is he aware that felons often have trouble finding any job, let alone one paying well enough to cover more than basic living expenses?

By definition, a process successfully navigated by less than two-tenths of 1 percent of affected individuals is challenging and difficult.

The problem isn’t how well-meaning people in the governor’s office handle the applications. The problem is a system that makes a fundamental right conditional on a major investment of time and money by people who have few resources.

PATE MISREPRESENTS THE GOALS OF GRIFFIN’S ALLIES

In his newspaper commentary, Pate claimed,

It is equally troubling to hear Washington, D.C.-based special interest groups come to our state and testify to our Supreme Court that Iowa should allow imprisoned child molesters, murderers and rapists [to] vote in our elections. That is what happened in Des Moines on Wednesday. Their view does not represent Iowa values.

During his April 4 interview on WHO Radio, Pate characterized the view of such groups as follows (starting around the 2:45 mark):

If you are a murderer, a rapist, a child molester, they should not lose their voting rights, that those people should be able to vote even while they’re in prison. There’s no penalty, no time out, nothing. And I was just offended. I sat there, Really? I think if you walk downtown Des Moines or Vinton, Iowa, or Carroll, Iowa, and you ask the average Iowan, and I don’t think they’re going to go along with that line.

Pate returned to the issue around the 8:20 mark:

I don’t think that anybody here in Iowa really genuinely wants a felon–particularly somebody who’s serving in prison right now–having their voting rights. I couldn’t–I almost fell off my chair in the Supreme Court chambers when the attorney for one of the groups who was speaking there said, when the judge asked her, she said, “I think they should get to vote always. They don’t lose their voting rights.” So while they’re serving time in Fort Madison, or in any of our prisons in Iowa, they get to vote. They get to vote for the judges. They get to vote for the county prosecutors. They get to vote for the sheriffs. I just, I just don’t–you’re insulting my intelligence as an Iowan. I just can’t believe anybody really in Iowa is going to bite on this one. But you know, it’s in the hands of the judges right now on this one.

Labeling political opponents as outsiders while aligning yourself with “average Iowans” is a classic demagogue’s tactic. But lots of people who were born and raised in Iowa support Griffin’s position, including Polk County Auditor Jamie Fitzgerald and members of the ACLU, NAACP, and the League of Women Voters.

Pate’s cheap shot at “special interest groups from the east coast” also misrepresented the plaintiff’s position.

The ACLU of Iowa and Griffin have not asked the Iowa Supreme Court to allow felons to vote from prison. Justices could rule that Griffin’s non-violent drug crime was not “infamous” without extending voting rights to Iowans who are serving time.

In its amicus brief urging the Supreme Court to “restore full voting rights – without undue burden or discretionary procedures – to Iowans with felony convictions,” the NAACP concentrated on the racially disparate impact of felon disenfranchisement and the history of such policies in Iowa and elsewhere, the reasons why Iowa’s policy disproportionately affects African-Americans, and evidence supporting fewer restrictions on voting by people with criminal convictions. The brief discussed benefits of allowing “released prisoners” to participate in the political process. It cited opinion polls showing widespread public support for letting people “who have completed their sentence” vote again.

During her presentation to the Iowa Supreme Court on March 30 (beginning around the 27:30 mark of this video), the NAACP’s attorney Coty Montag talked about the “expansion of voting rights to individuals with felony convictions” as a way to make communities more inclusive “by increasing civic engagement and reducing recidivism.” She further explained that the organization supports a definition of “infamous crimes” that would disenfranchise only those whose crimes represent “an affront to democratic governance.”

The exchange that spurred Pate’s most explosive talking point happened around the 29:30 mark. Responding to a question from Justice Thomas Waterman, Montag said the NAACP would support the right of incarcerated individuals to vote by absentee ballot from prison.

However, the next part of the exchange belies Pate’s claims. When Justice David Wiggins followed up by asking whether imprisoned individuals should be considered residents of where they are incarcerated or where they came from, Montag responded, “Your honor, we think that’s a separate issue, but we would ask the court to look at the residence of where they’re from instead of where they’re incarcerated.”

We’ll return to that point below, though it wasn’t a major part of the Griffin oral arguments. On the contrary, after Montag answered Wiggins’ question, Chief Justice Mark Cady (the author of the decision that inspired this case) quickly directed the discussion back to the main question before the court: the definition of “infamous crimes.”

PATE TO REPUBLICAN ACTIVISTS: “I NEED YOUR HELP”

Pate had been campaigning for a delegate slot at the Republican National Convention from Iowa’s first Congressional district. Shortly before the April 9 district conventions, he says, he decided against running for RNC delegate and chose instead to address hundreds of GOP activists in Cedar Falls, Fort Dodge, and Creston. By Pate’s account, he wanted to promote the secretary of state’s “Honor a Veteran” program and talk about the felon voting case.

Side note: the Secretary of State’s official website explains, “Honor a Veteran is a program that honors the sacrifices that Veterans have made throughout history to protect our freedoms and our sacred right to vote.” Not “privilege.”

Pate has not responded to my request for the full text of his prepared remarks to GOP district convention delegates. Starting Line’s Pat Rynard wrote up parts of the speech at one gathering. His post is consistent with reports on what Pate told fourth district delegates about liberals wanting “unelected judges” to let criminals vote.

“I want to let you know what the other side is up to,” Pate began his speech to the Republican 3rd District attendees in Creston. “We had a hearing before the Iowa Supreme Court last week during which the ACLU of Iowa and an out-of-state liberal special interest group came and argued before the Supreme Court that child molesters, rapists, murders who were all thrown behind bars should be able to vote in our elections.”

Like Griffin, most disenfranchised Iowans committed non-violent felonies. But “child molesters, rapists, and murderers” make for better red meat than rehabilitated drug addict, community volunteer, and mother of four. Back to Starting Line’s account:

“I think it’s been clear to most of us that people convicted of infamous crimes lose their voting privileges,” Pate argued in his speech. “That’s a fact. We have precedent dating back more than a hundred years as maintain that a felony is an infamous crime. All the towns you represent, go down to your main street, you ask someone, ‘Do you think a felon, someone who is a murderer, a rapist, a sexual assault person, is eligible?’ I think the answer is pretty clear.” […]

“The liberals want unelected judges, not we the people, to ignore the Iowa Constitution,” Pate said. “They want to allow all felons, even those behind bars for the most serious crimes imaginable to decide who our elected representatives should be. Think about the impact on local elections if we let that happen. If you look over at the 1st District, we have 1,100 inmates at the Anamosa state penitentiary. The 4th District has 1,200 inmates at Fort Dodge. And go down the list at Fort Madison and on down.”

“These people will be deciding who the next County Sheriff is, who should be the County Attorney, who should be the judges, the state representatives and on and on and on,” Pate continued. “That’s what the liberals want because they think it will help them win elections, and I need your help so that we can fight against that.” […]

“The left-wing doesn’t want there to be any process,” Pate suggested. “They want child molesters and they want rapists and murders to play a larger role in determining who our elected representatives are and who they’ll be.”

I assume Pate meant to say something like, “The liberals want unelected judges to ignore the Iowa Constitution instead of letting we the people decide.”

Again, the ACLU of Iowa has not asked the Iowa Supreme Court to let felons vote while still in prison.

The NAACP’s attorney told Justice Wiggins, “we would ask the court to look at the residence of where they’re from instead of where they’re incarcerated.” (emphasis added) In other words, 1,100 inmates in Anamosa would not be voting for the Jones County attorney. Most inmates in Fort Dodge or Fort Madison would not be voting in those districts’ state legislative races.

Even if Griffin prevails, child molesters, rapists and murderers would not necessarily regain their voting rights. The Iowa Supreme Court could adopt a new standard for “infamous crimes,” covering class A felonies or crimes of “moral turpitude” but not crimes such as operating while intoxicated or delivery of a controlled substance.

Getting back to the question that launched this post: why is Pate seeking so much attention for his spin on the Griffin case now?

When I asked the Iowa Attorney General’s Office for reaction to Pate’s op-ed column and reported remarks to the GOP district conventions, I got the answer I expected from communications director Geoff Greenwood: “We don’t comment on pending litigation.”

Of course they don’t. For the same reason, ACLU of Iowa executive director Jeremy Rosen e-mailed this response to my query:

“The Secretary of State’s comments are obviously incendiary, and while he is improperly, and perhaps even unprecedentedly, attempting to try this case in the court of public opinion with mischaracterizations of the parties, the law, and the lawsuit, we will not take the bait and do the same. Instead, we respect the legal system and await the Court’s decision.”

Pate has not responded to my request last week to clarify what he meant when he told GOP convention delegates, “I need your help so that we can fight against that.” Was he foreshadowing some kind of civil disobedience on his part, like refusing to add the names of felons to Iowa’s voter rolls?

Was he alluding to a political campaign against retaining Supreme Court justices who might redefine “infamous crime”? Three of the justices whom I consider likely to lean toward Griffin’s position are up for retention this November: Chief Justice Cady, Justice Brent Appel, and Justice Daryl Hecht.

Railing against “unelected judges” who overturned 100 years of precedent sounds a lot like the television commercials social conservatives ran against three Iowa Supreme Court justices during the fall of 2010:

Activist judges on Iowa’s Supreme Court have become political, ignoring the will of voters and imposing same-sex marriage on Iowa. Liberal, out-of-control judges ignoring our traditional values and legislating from the bench, imposing their own values on Iowa. If they can usurp the will of voters and redefine marriage, what will they do to other long-established Iowa traditions and rights? Three of these judges are now on the November ballot. Send them a message. Vote no on retention of Supreme Court justices.

Substitute “letting rapists, murderers, and child molesters vote” for “imposing same-sex marriage on Iowa” and “redefine infamous crimes” for “redefine marriage,” and you’re good to go.

Or, adapt part of the script from another 2010 anti-retention ad, inserting “let rapists, murderers, and child molesters vote” for “redefine marriage”:

Some in the ruling class say it’s wrong for voters to hold Supreme Court judges accountable for their decisions. […]

If they can redefine marriage, none of the freedoms we hold dear are safe from judicial activism.

To hold activist judges accountable, flip your ballot over and vote no on retention of Supreme Court justices.

Groups still holding a grudge over the 2009 marriage equality ruling (which Cady wrote and Appel and Hecht joined) might even finance tv ads exploiting the felon voting case, if the majority finds in Griffin’s favor. An emotional appeal about voting rights for brutal criminals would be more effective than a stale diatribe about same-sex marriage, which is now legal nationwide.

Television commercials similar to the 2010 anti-judge spots failed to oust Wiggins, who was up for retention in 2012. Since Democratic turnout is higher in presidential election years, a hypothetical anti-retention campaign against Cady, Appel, and Hecht would be a steeper hill to climb. On the other hand, Pate clearly believes it’s a political winner to bash “unelected judges,” the “left-wing” and “special interest groups from the east coast,” who supposedly don’t reflect our Iowa values.

As mentioned above, Pate has not responded to my question about whether he would seek Republicans’ help in trying to oust Iowa Supreme Court justices, if the Griffin ruling goes against him.

Whatever Pate’s intentions were before he riled up those district convention audiences, to my ear his words sound like a warning shot to justices: if you redefine “infamous crimes,” expect political fallout. I’ll make sure of it.

Another interpretation of “I need your help so that we can fight against that” comes to mind. When Pate was secretary of state during the 1990s, he used the office as a springboard for a gubernatorial bid. He even received a formal reprimand for having staffers in the Secretary of State’s office do campaign work for him.

Perhaps distributing his newspaper commentary widely, going on a leading conservative radio program, and putting himself in front of delegates at three district conventions were part of a plan to make Pate a hero to the right before a 2018 re-election campaign or run for higher office. Maybe Pate was only trying to recruit GOP activists for the fight against “liberals” trying to win this year’s elections, ostensibly by getting more criminals into the electorate.

Not being a mind-reader, I don’t know whether Pate was promoting his own political ambitions or trying to influence Supreme Court justices as they consider Griffin’s appeal. Either way, it’s inappropriate for a statewide official to use such inflammatory rhetoric about a pending court case.

2 Comments

Smack!

Now that’s a heroic smackdown. Pate deserved it. I had thought maybe his own election had been a good thing after the folly of Matt Schultz, the transparent use of the office as a springboard by Culver, and the likelihood that 2014’s Dem candidate had the same thing in mind. But apparently we have gained little.

Oh, for the days of Michael Mauro!

iowavoter Wed 20 Apr 11:16 PM

FORMS

Thoughtful article ! I Appreciate the insight , Does anyone know if I might find a blank a form document to use ?

dorthachristmas Wed 25 May 6:58 AM